“Tried to prove the ship’s captain was negligent”

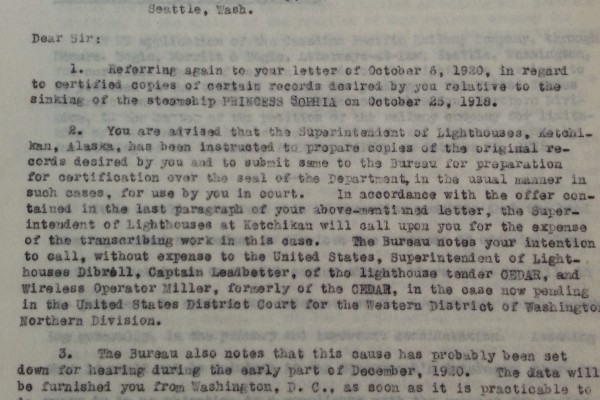

Immediately after the sinking of the Sophia, rumors began to spread as to why the Sophia sank. Why wasn’t anyone saved? What went wrong? The main question, though, was how such an experienced captain was not able to bypass such an infamous reef. The case of IM Brace. et al .vs. CPR attempted to discover what really happened on that dreadful night of October 24th, 1918, when the Princess Sophia ran ashore on the Vanderbilt Reef. The trials were meant to begin in December of 1918, when all the facts about the incident were still fresh in everyones minds. However, the main antagonist of this story, W.C. Dibrell, Superintendent of the Juneau lighthouse, was weary of dominance, and did not want the men who had been on the Cedar on the night of the sinking to give their testimony to the court. The trials were postponed to January 17th, and then again to January 24th. After much conversing between the lawyers of the CPR – Bogle, Merritt, and Bogle – and W.C. Dibrell, Dibrell reluctantly gave his permission to the members of the Cedar who were aboard during the time of the attempted rescue to testify. Before this, he is quoted as saying;

“If the Cedar is up and running by the time that the

employees were supposed to go down to Victoria,

and Vancouver to give their testimony, then it is highly

unlikely that the lighthouse would give their employees

time off”

-January 4th, 1919.

Promptly after he sent this letter to The Barristers Pooley, Luxton, and Pooley, he sent one to his men, stating;

“Permission has been granted to all those who wish

to testify, granted that no expense will be paid by the

Government of the United States, […] ship records

may be used. but by no mean will they leave the hands

of any employees.”

-January 6th, 1919

Dibrell still did not make it easy. Official documents show that instead of responding with any information that could have allowed for the court to come to an earlier conclusion to case, he would respond to the lawyers by telling them they need to fill out the proper affidavit. After some time, Dibrell made the arrangement that his men would give their testimony to the lawyers when they were docked at the ports in Vancouver, BC, with one condition: any official document or record that was given to the court from the Cedar or the Juneau lighthouse would remain in the hands of the members of the Cedar. Without hesitation, the Lawyers would accept this condition. Dibrell was contacted by the wreck supervisor, Mr. John Macpherson, to acquire more documents. Even then, he sent Macpherson a telegram saying that he would have to fill out the correct affidavit form before he could be given any information on the sinking.

When asked for the weather records on the night of the foundering, Dibrell, reluctant as always, said that they had nothing important written down, and it was worthless to anyone else. He claimed that there were few notes on the documents regarding the weather, and unless they absolutely needed this “useless” information, they shouldn’t waste their time with it, and again asked for the proper forms to be filled out before he would give the records to the lawyers of the CPR.

Bogle, Merritt, and Bogle were told that if they wished to acquire any documents from the lighthouse, or the Seattle Port Authority in general, they would have to bear any expense that would arise. These expenses included up to $120 a month for copying any journal abstracts of Eldred Rock or the Sentinel Island lighthouse stations, the deck log of the Cedar, the report of assistance rendered, and radio messages received and sent by the Cedar to the Princess Sophia.

On the 27th of January, the boys who had worked on the Cedar were told to stop in Vancouver to give their testimonies to the lawyers of the CPR. However, Captain Leadbetter, someone who was considered to be quite an important witness for this case, was not able to attend at the same time as the rest of the crew of the Cedar. Dibrell then stated, “find him if you can.” It was almost two years later before the lawyers finally located Captain Leadbetter and took his testimony.

Verdict:

Fourteen years after the trial began, the CPR was charged with negligence, and were initially ordered to pay $2.5 million in damages to the crew and families of the passengers of the Princess Sophia. This order would be revoked within the next fourteen days because of the Limited Liabilities act of 1851. This act would limit the CPR’s responsibilities to the passengers, luggage, and freight fares. This means that the CPR would only have to pay $643.50, or $2 per passenger, with the insurer company paying another $250,000 for damages.

Click here to look at more images of the Correspondence between the Lawyers, Mr. Dibrell, and Mr. MacPherson.