“If we are to understand why Aboriginal and Eurocentric worldviews clash, we need to understand how the philosophy, values, and customs of Aboriginal cultures differ from those of Eurocentric culture. Understanding the differences in worldviews, in turn, gives us a starting point for understanding the paradoxes that colonialism poses for social control.”

–Leroy Little Bear

Worldview

The roots of Learning to Listen grow from the deepest parts of our cultures. We are each the collection of perspectives we learned as we grew up, learning from those around us – our parents, our friends, TV, the land. Not all of this learning is obvious – developmentally we learn through watching, through participating, and through doing. Sometimes what we learn isn’t what the person teaching us literally tells us. Sometimes the person telling us that it’s wrong to steal continues to steal from us every day.

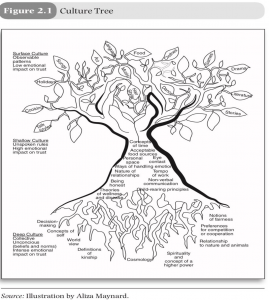

Culture is where we derive our worldview. And it’s that worldview (our “view on the world”) that infuses images, symbols, experiences, and our day-to-day actions with meaning. It orders our universe, it puts us inside our geography and society, it informs what decisions we make, and explains how we relate to others. It manifests in the clothes we wear, the music we are drawn to, and even how we experience time, history, gender, desire, good and evil, clean and dirty, what is socially acceptable and not, etc.

Like his description above, Leroy Little Bear (Blackfoot) sees worldview as one of the major distinctions between Indigenous people and the dominant colonial culture. This is a perspective by many Indigenous authors, thinkers, practitioners, and knowledge keepers from many different nations, communities, and traditions. Vine Deloria, Jr. (Standing Rock Sioux) explains how the dominant worldview’s focus on time, on progress, moves us away from experiencing the world as a series of mutual relationships. Linda Tuhiwai Smith (Ngāti Awa & Ngāti Porou iwi) has used a Māori worldview to counter the ways the oppression of Indigenous peoples in universities through the methodologies that we settlers create to privilege knowledge.

A worldview is a “view on the world,” and a life-world is the world we experience daily, with our worldview giving meaning to those things that happen in a day. A life-world is essentially the “world we experience” as living beings.

Dominant Worldview

As Vine and Leroy have explained, the Euro-North American or dominant worldview severs attachments. It isolates and is constantly moving away from something (a beginning) and towards something (an end point). Events in this worldview happen linearly, one after the other, and often provide meaning to all experiences after those events (like the crucifixion of Jesus or the big bang).

As Vine and Leroy have explained, the Euro-North American or dominant worldview severs attachments. It isolates and is constantly moving away from something (a beginning) and towards something (an end point). Events in this worldview happen linearly, one after the other, and often provide meaning to all experiences after those events (like the crucifixion of Jesus or the big bang).

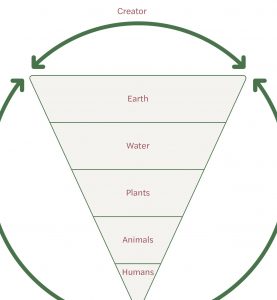

The Bible and Frances Bacon and the scientific method codify humans as distinct and special on earth. It is in this worldview where man (specifically) is the master of all of the resources that the earth provides. This doesn’t mean that Christianity and Bacon’s scientific method are identical. It doesn’t even mean that they complement each other or agree. What it does mean is that both position humans as individuals within a broader universe of individual parts, and we are moving away from an event and towards another event. Within this cosmology humans are elevated above animals, whether to govern (Christianity) or to steward (many sciences). Both of these worldviews also state that they are somehow universal, and applicable in all settings with no possibility of an alternative.

For many of the knowledge keepers mentioned above, and in my experiences over the 40-some years of living here, it’s this separation, isolation, and confinement from that which is alive creates the potential for the violence of settler colonialism, for class warfare, for extractive war against the ecosystems that give us life, all thew while encouraging racism, heteropatriarchy, with an inability to see one’s self as a destructive, complicit agent.

Most dangerously for me, is that it detaches our heart from our heads.

Relational Worldviews

“In Aboriginal philosophy, existence consists of energy. All things are animate, imbued with spirit, and in constant motion…interrelationships between all entities are of paramount importance, and space is a more important referent than time.”

-Leroy Little Bear

In many Indigenous worldviews space is more important than time. Space between relations, space between mountain and ocean, space between the last salmon spawn, space between each of us. When something happens is less important than where. Moving forward isn’t that important compared to maintaining relationships that focus more on moving between spaces where things happen and continue to happen.

In many Indigenous worldviews space is more important than time. Space between relations, space between mountain and ocean, space between the last salmon spawn, space between each of us. When something happens is less important than where. Moving forward isn’t that important compared to maintaining relationships that focus more on moving between spaces where things happen and continue to happen.

Worldviews describe a universe that is local in many ways, because most of human history has not been spent in motion, but in place. These worldviews don’t offer global truths because they are localized.

Take one specific, simple example: Trees aren’t important because once they are cut down and polished they sell well in another part of the world. Trees are important because of their uses where they grow and live, and because of the life they provide locally.

When working through a problem, trying to figure out how to get through a rough period, or just picking something to eat for dinner, relational worldviews connect the heart and the head. They reveal our capacity to learn from other beings, those who have always been teaching us what plants to eat, what berries to avoid, and where not to swim.

Animals (or more-than-humans) can teach us because we share common ancestors – we all come from the Earth, we all need Water to live, and we all share breath. In a relational worldview, none of us are worse than others, and each adds value to the universes we live in.

Understanding ourselves as kin stops us from cutting down all the trees in one part of the world to make money for people in another part of the world. It also stops us from abusing each other because of our gender, because of the colour of our skin, because we do things differently, and because we’re a different species.

The Problem with Worldviews**

When you feel that the trees need protection, even if Indigenous people say to get the fuck off their territory, why do you think your answer is right?

This is the problem with worldviews, and it is specifically the probelem with the worldview that is governing settler colonial states…[rewrite from here>]

Indigenous knowledge keepers, activists, authors, and celebrities have been explaining this since colonization. Expecting Indigenous people to save settlers from ourselves, and to save the Earth from the environmental destruction that the dominant worldview allows is foolish and probably very insulting to Indigenous people. Especially (as Jeff Corntassel [Tsaligi] [with Snelgrove & Dhamoon] has written about) since Indigenous people have been teaching us how to become relational the entire time.

The problem then isn’t that people are being silent or keeping relationality a secret. The problem is that settler society must relearn what it means to listen. Maintaining a worldview that puts humans as the best, that sees humans as distinct from the land, means our ears are still blocked by the noise of our own arrogance. It means we might hear words, and even repeat them, it also means we won’t understand what is being said to us.

The more you read through this site, the more you will see how this page about worldviews is very much the roots at the base of a seedling as it starts to grow. Knowing that we (settlers) must learn to listen, that we (settlers) can step away from knowledges that hurt us, that kill our children and neighbours and destroy the Earth, doesn’t suddenly explain the how.

What it does promise though is that once we (settlers) start to listen and can actually start to understand our place in a wide web of interrelations, it means that our life-worlds (the way we experience things in a day-to-day way, informed by our culture and worldview) are starting to change.