“We acknowledge and respect the Lək̓ʷəŋən (Songhees and Xʷsepsəm/Esquimalt) Peoples on whose territory the university stands, and the Lək̓ʷəŋən and W̱SÁNEĆ Peoples whose historical relationships with the land continue to this day.”[1] This is what we hear constantly as students or faculty at the University of Victoria, but what does it mean not only in the context of the Indigenous peoples’ histories but also in relation to the history of this institution? The question is all the more pressing since the history of the Lək̓ʷəŋən peoples predates the university by so much it is in effect an independent story.

Beginning in the early 19th century, the Lək̓ʷəŋən peoples were composed of many smaller groups. They each occupied certain areas around southern Vancouver Island; however, for the purposes of this post we will focus on the Chekonein peoples. They lived around Cadboro Bay, up to Cordova Bay, and around the university campus, with 24 different burial and village sites throughout this area. There was a village and burial site at Cadboro Bay, called Sungyaka, meaning snow patches. It was an important winter village used for fishing and hunting. The Chekonein peoples relied on the fish, the shellfish, the waterfowl and seal. The bay later became known as Cadboro Bay after James Douglas’ ship, which he used to survey sites for Fort Victoria in 1842. [2]

Cadboro Bay in 1870 – Found in the University of Victoria’s Special Collections and Archives

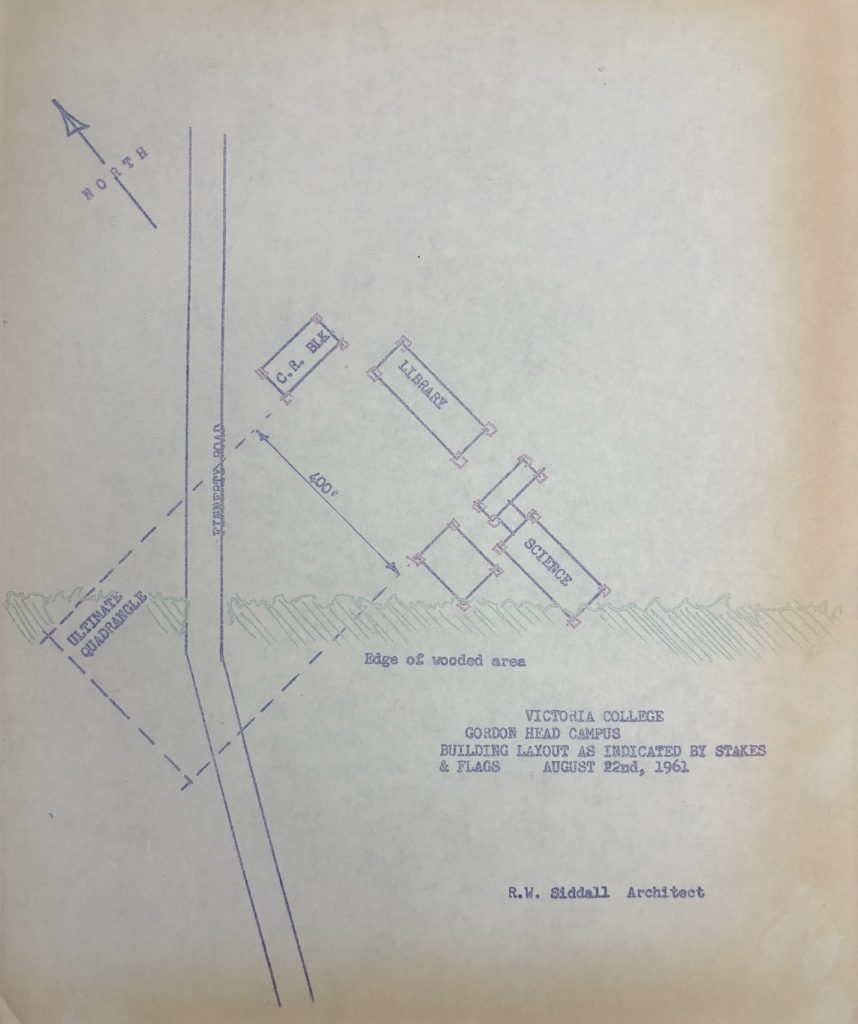

Only a couple of years later, the Chekonein peoples relocated to Victoria Harbour to be closer to Fort Victoria’s trading post. Unfortunately, due to the ever-growing settler population, the Chekonein peoples were forced to relocate many more times. In 1911 the Lək̓ʷəŋən peoples were paid a nominal sum and forced to move onto a reserve. Over the last 200 years the village and burial sites have been mostly destroyed, and the Indigenous populations were decimated by the intentional spread of smallpox, leaving little archaeological evidence remaining. Nevertheless, there are clear indicators that the Chekonein peoples had a smaller village on campus where the Elliott building parking lot is today.[3]It was used as a base to hunt and gather things like deer and camas roots, which were found on the southeast side of what is now campus.[4] As settlers took over the land that would become UVic’s campus, it changed hands in parcels and was at one point co-occupied by the Hudson’s Bay Company and the Canadian military, who used it as a training camp during the Second World War. The land was finally purchased for the university between 1959-1961, initially housing just one portion of Clearihue, the Elliott building, and the McPherson Library.

Original Gordon Head Campus layout – Found in the University of Victoria’s Special Collections and Archives

The construction of the university in the early sixties was organized by Victoria College, which had been working in junction with UBC since 1920, meaning that if you earned a degree from the college, you would have a diploma from UBC. When the Gordon Head campus was opened in 1963, it was the first independent university on Vancouver Island, and the original Lansdowne campus where Victoria College was, is where Camosun College is today.[5]

In the end, knowing the overarching history of this land and the university, provides a more active and personal acknowledgement when recognizing the Lək̓ʷəŋən peoples’ connection to this place. It allows us to fully respect the history of the Indigenous peoples who have been on this land for time immemorial and reminds us to make a conscious effort toward reconciliation. Additionally, it allows us to build a connection with the university and recognize the increasing respect the University shows toward local Indigenous populations, cultures, and histories. The Food4Learning project’s goal is to create a learning garden behind the library that can act as a space not only to learn about the past but also about how this land was used before a colonial presence was established. Ideally this garden would grow plants with historical and educational significance, including many that were traditionally used by the Lək̓ʷəŋən peoples. The objective would be to create a modern-day connection to Lək̓ʷəŋən peoples’ past while also finding easy everyday ways to take small steps toward climate action.

Sources

“Cadboro Bay.” InteractiveResource. University of Victoria, B.C., Canada. Accessed November 13, 2025. https://bcgenesis.uvic.ca/cadboro_bay.html.

UVic.Ca. “Culture & Protocol – VP Indigenous – University of Victoria.” Accessed November 13, 2025. https://www.uvic.ca/ovpi/ways-of-knowing/culture-and-protocol/index.php.

University if Victoria (B.C). University of Victoria (B.C) fonds. Special Collections and University Archives, University of Victoria Libraries, Victoria, British Columbia.

University if Victoria (B.C). Gordon Head Exhibit Project. Special Collections and University Archives, University of Victoria Libraries, Victoria, British Columbia.

[1] “Culture & Protocol – VP Indigenous – University of Victoria,” UVic.Ca, accessed November 13, 2025, https://www.uvic.ca/ovpi/ways-of-knowing/culture-and-protocol/index.php.

[2] “Cadboro Bay,” InteractiveResource, University of Victoria, B.C., Canada, accessed November 13, 2025, https://bcgenesis.uvic.ca/cadboro_bay.html.

[3]1995-034, box ¼, folder 1.12, Gordon Head Exhibit Project. Special Collections and University Archives, University of Victoria Libraries, Victoria, British Columbia.

[4] 1995-034, box ¼, folder 1.11, Gordon Head Exhibit Project. Special Collections and University Archives, University of Victoria Libraries, Victoria, British Columbia.

[5]1984-021, box ¾, folder 3.1, University of Victoria (B.C) fonds. Special Collections and University Archives, University of Victoria Libraries, Victoria, British Columbia.

Leave a Reply