While 1914-1918 marked the war years for Canada, China was involved in its own civil war starting in 1911 and did not join the Allied effort in Europe until 1917. The war effort in Canada and China pulled the Chinese Canadian community in Victoria in two different directions. While involvement in the Canadian war effort was not prominent, Victoria’s Chinatown contributed directly to victory loans and myths of Chinese Canadian enlistment persist, though it is unclear if any signed up in Victoria.

Victoria’s Chinatown also raised funds for the victory loans during World War II. Image I-01011 courtesy of the Royal BC Museum and Archives.

Looking overseas, the rise of political organizations in Victoria’s Chinatown was indicative of the level of involvement of ‘overseas’ Chinese in the revolution. These organizations raised large amounts of money to support their respective sides in China, and some Chinese Canadians even left for China to get directly involved.

The Canadian War Effort

Victory Loans

One of the way’s Victoria’s Chinatown contributed to the Canadian war effort was by fundraising, quite successfully, for victory loans, a fundraising program run by the federal government during the two world wars to raise money for the effort. Though the program started in 1915, Victoria’s Chinatown was not targeted until November 1917. It was then that Victoria’s victory loan organizers made plans to publish posters in Chinese dialects for distribution throughout Chinatown.[1] They also asked the Kuonmintang newspaper in Victoria, The New Republic, to publish information in Chinese languages about the victory loan process in preparation for canvassing.[2]

Apparently Chinese Canadian support for victory loans was high, partially because of their sales director, Harry Hastings. Hastings raised $5,000 on his first day of sales in November 1918, and though it was about $5,000 less than other fundraisers, the Daily Colonist newspaper and the victory loan organizers applauded his progress. Hastings promised to beat his 1917 total by $10,000, when he raised $30,000.[3]

Many of the big contributions were made by Chinatown’s merchants, who were enjoying a period of economic success. When the results of the victory loan drive were calculated, Hastings had raised $40,000 from Victoria’s Chinatown, beating his 1917 total. Fundraising officials thought that this total could have reached $100,000 if the same levels of advertising were employed in Chinatown as in other neighborhoods.[4] As a comparison, when Sun Yat-Sen, the Chinese revolutionary and nationalist, arrived in Victoria in 1911, Victoria’s Chinatown raised $30,000.[5]

Military Service

The extent of the involvement of Chinese Canadians from Victoria in military service is relatively unknown. Most authors on Chinese Canadians during the World War I period acknowledge that some Chinese Canadians served, but little information is available on where they registered or how many there were.[6] Library and Archives Canada’s database of soldiers in the Canadian Expeditionary Force only lists three soldiers whose birthplaces were in China, and attestation forms did not track racial or ethnic origins.[7]

During the early 1900s, the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association (CCBA) in Victoria, a community organization that managed records for the community as part of its mandate, does not record any deaths linked to war either. The CCBA did note when Chinese Canadians died overseas, for example those from Victoria who died in the sinking of the Princess Sophia, but there were no records for deaths in Europe and none of the men of military age who died in Victoria during the war era and the early 1920s served in the Canadian Expeditionary Force.[8] It is highly likely that some Chinese Canadians served, perhaps even out of Victoria, but it is still a mystery who they were and where they were from.

Chinese Revolutionary War Effort

Contributions to the 1911 Revolution

A photo taken when Sun Yat-Sen visited Victoria in 1911, prior to the revolution. Source: University of Victoria Archives, David Lee Fonds, ca. 1911.

Most of the contributions to China’s 1911 Revolution from Canada also came in the form of fundraising by Chinese Canadian political associations. When Sun Yat-Sen toured Canada in 1911 prior to the revolution, Victoria’s Chinese Canadian community alone raised $30,000, of $70,000 total raised in Canada, to contribute to the cause.[9] Because of their contributions, the Victoria chapter of the Chee Kung Tong, the main organizers of the fundraiser, received designation as a political party by the new Chinese government.[10] There are even rumours that in response to tensions in China, Victoria Chinese Canadians formed several militia units that left for China in 1916 to support Sun Yat-Sen’s government. Some returned home in 1917, but it is said that some remained in China to join Sun Yat-Sen’s government and act as his personal bodyguards. [11]The actions of Chinese Canadians across Canada in support of the 1911 revolution increased ties between China and Chinese Canadians as ‘overseas’ Chinese were accepted as part of Chinese society and had Chinese residency even while living abroad.[12]

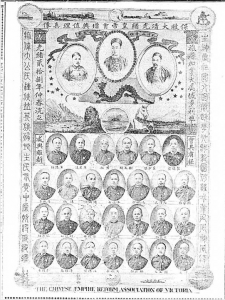

A poster of the leaders of the Chinese Empire Reform Association of Victoria, an organization which supported the Qing dynasty. Source: University of Victoria Digital Collections, Victoria’s Chinatown, ca. 1902.

Conflicting views

However, not all Chinese Canadians in Victoria’s Chinatown were unanimous on which political party they supported – Sun Yat-Sen’s revolutionary regime in the south, or the government in the north – and these conflicts sometimes broke out in violence. In October 1916, the Daily Colonist reported violent protests between different factions in Chinatown, including those that controlled the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association and nationalist factions. Also involved was the “Chinese newspaper,” presumably The New Republic, the Kuoamintang newspaper. [13] Though little further information about the incident is available, modern books on Chinatown also note the tensions between various political organizations. In 1918, a Kuomingtang member in Victoria shot and killed a visiting Chinese politician from the government in the north.[14] So-called ‘tong wars’ sparked in Victoria between various political factions even spread to Chinatowns across Canada as they wrestled with similar internal divisions.[15]

Footnotes

[1] “Demonstration for First Day: Victory Loan Drive to Be Inaugurated by Enthusiastic Participation of Thousands of Workers,” Daily Colonist, 3 November, 1917, pg 7. http://archive.org/stream/dailycolonist59y283uvic#page/n6/mode/1up/search/chinatown.

[2] “Plans Completed for Pledge Distribution,” Daily Colonist, 9 November, 1917, pg 7.http://archive.org/stream/dailycolonist59y288uvic#page/n6/mode/1up/search/chinatown

[3] “Local Firms are Getting In Line,” Daily Colonist, 3 November, 1918, pg 7. “Over Half of Quote in First Six Days,” Daily Colonist, 3 November, 1918, pg. 17. http://archive.org/stream/dailycolonist60y286uvic#page/n6/mode/1up/search/chinatown

[4] “Citizens Rpdocued Millions for Canada: City’s Response to Victory Loan Appeal Results in $6,500,000 Being Poured in Nation’s Coffers,” Daily Colonist, 19 November, 1918, pg. 10, http://archive.org/stream/dailycolonist60y300uvic#page/n9/mode/1up/search/chinatown.

[5] Charles Sedgewick, “Context of Economic Change and Continuity in an Urban Overseas Chinese Community,” 1970, CA UVICARCH AR113, University of Victoria Special Collections and University Archives, https://dspace.library.uvic.ca//handle/1828/3216, 147.

[6] Jin Tan and Patricia E. Roy, The Chinese in Canada, Canada’s Ethnic Groups (Saint John, N.B.: Canadian Historical Association and Keystone Printing & Lithographing, Ltd., 1985), http://www.collectionscanada.gc.ca/obj/008004/f2/E-9_en.pdf, 15. Edgar Wickberg, ed., From China to Canada: A History of the Chinese Communities in Canada (Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1982), 119.

[7] “Personnel Records of the First World War Database,” Library and Archives Canada, http://www.bac-lac.gc.ca/eng/discover/military-heritage/first-world-war/personnel-records/Pages/list.aspx?BirthCountry=China& (November 16, 2016).

[8] University of Victoria Special Collections and University Archives, Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association, CA UVICARCH AR030, 2011-004 01/H/02-03, Death Certificates and Burial Permits for Chinese in Victoria, 1902-1923.

[9] David Chueyan Lai, Chinatowns: Towns Within Cities in Canada (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2000), ProQuest ebrary, 206. Sedgewick, “Context of Economic Change and Continuity in an Urban Overseas Chinese Community,” 147.

[10] Lai, Chinatowns, 206.

[11] Wickberg, From China to Canada, 105. Paul Yee, Chinatown: An Illustrated History of the Chinese Communities of Victoria, Vancouver, Calgary, Winnipeg, Toronto, Ottawa, Montreal and Halifax (Toronto: James Lorimer & Company Limited, 2000), 33.

[12] Tan and Roy, The Chinese in Canada, 6.

[13] “Look for More Trouble,” Daily Colonist, 11 October, 1916, pg. 7, http://archive.org/stream/dailycolonist58y261uvic#page/n6/mode/1up/search/chinatown. “Newspaper Heads Involved in Case,” Daily Colonist, 31 October, 1916, pg. 7, http://archive.org/stream/dailycolonist58y278uvic#page/n6/mode/1up/search/chinatown.

[14] Yee, Chinatown: An Illustrated History of the Chinese Communities of Victoria, Vancouver, Calgary, Winnipeg, Toronto, Ottawa, Montreal and Halifax, 33.

[15] Lai, Chinatowns, 211.

Primary author: Kate Siemens