Anti-Chinese Sentiments in British Columbia

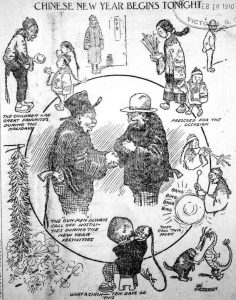

“Chinese New Years Begins Tonight,” Vancouver Daily Province, 8 Feb 1910. Source: BC Archives, Item B-08249

Chinese immigrants and Chinese Canadians in BC experienced broad racism beginning with the Gold Rush and the construction of the Canadian Pacific Railway during the late 1800s. In both of these instances, large numbers of poor Chinese men arrived in the province alongside many others with the same goals. However, because of their precarious financial position in China, these immigrants were willing to work for lower wages than other white immigrants. Most Chinese men sent what little money they made back to their families in China. The practice of working for lower wages and sending the money home affected their standing in white, Anglo-Canadian society. Firstly, it incited anger among workers who were not being hired because Chinese labourers would work for less. Secondly, their lower incomes meant that many men lived in close quarters, which often bred disease and general “uncleanliness” that Anglo-Canadians began to associate specifically with Chinese Canadians. To the young British province, none of this was acceptable.

While considered useful labourers by early governments, Chinese immigrants were ultimately deemed unpreferable as settlers in the new province. After the completion of the railway, the federal government imposed a series of head taxes to dissuade Chinese immigrants from coming to BC. In 1885, the initial tax was $50 and, by 1904, it peaked at $500 per person.[1]

Racism in Victoria

William Head Quarantine Station was partially built in response to perceived Chinese uncleanliness. A large Chinatown was established in Victoria, where many of the poorer Chinese Canadian workers gathered to live, work, and participate in the growing opium scene. As Chinatown grew, so did its reputation as a site of numerous easily transmutable diseases. With this reputation in mind, the quarantine station served two purposes: a site far from the city to detain infected individuals, and an inspection station for ships arriving from foreign shores. Because many of the people who lived Chinatown lived closely together and with poorer sanitation, there were relatively more sick individuals in Chinatown then elsewhere in Victoria. This was used as proof that the Chinese were biologically predisposed to be inferior.

William Head Quarantine Station Chinese Camp, 1917. Image B-01617 courtesy of the Royal BC Museum and Archives.

When the CLC arrived at William Head in 1917, they were met with the same bias that faced Chinese Canadians. After inspecting the boat, the station’s director found a few men had smallpox, so he quarantined all of the 2,057 men aboard. It became a self-fulfilling prophecy; a few people would get sick, they would be forced to stay in cramped living conditions, the disease would spread, and justification was provided to quarantine them.

While the station controlled the leper lazaretto on D’Arcy Island, 43 out of the total 49 men to sent there were Chinese. According to the station’s 1917 annual report, a few of them were men detained upon arrival with the CLC. By this time, the federal government had taken responsibility for leper colonies and ensured a standard of living. Those detained on the island received regular treatments, and their families received $25 per year as compensation.[2]

Cultural Racism in the War Effort

Before they were even put on a boat in China, the new members of the CLC were sent through an extensive preparation regiment that included standard procedures like delousing, but they also had their heads shaved and metal identification bracelets fixed around their wrists.[3] They were treated more like inmates than volunteers for the British Army.

This attitude was maintained across Canada and into France. On the journey itself, the transportation conditions were argued to be necessary in order to preserve secrecy. The governments in charge maintained that should the Chinese be allowed to leave the train at any point, word of the plan would spread to the Germans and none of the British ships with the CLC aboard would make it to France. Of course, the secrecy was also necessary to keep the presence of large numbers of Chinese immigrants from Canadians residents. While the head tax at this time was set at $500 to keep Chinese immigrants out, the Canadian government waived the fee for the 84,244 members of the CLC.[4]

Members of the CLC were not the only ones to experience racism during the war. Under the War Measures Act, the Censorship Office could monitor and intercept all incoming and outgoing communications from all Chinese Canadians communities in Canada. The Canadian government was paranoid about state secrets being leaked to enemy agents through China.[5]

In Canada and France, the CLC continued to face hardships. They were managed by white officers who could not speak their language and did not understand their cultures. This led to the belief that the Chinese lacked ambition and discipline, and were often punished when they did not respond in a way deemed normal by the British Army.

Even on their way back through Canada after the war, the CLC were still transported in total secrecy in locked and guarded trains despite there no longer being a military need. The Canadian government maintained their position of racist exclusion; the government did not want the CLC to leave the trains because they did not want them to stay in Canada. The position of Chinese exclusion from Canada was further cemented in 1923, when the Canadian government quietly passed a bill that barred all Chinese people from immigrating to Canada.[6]

Footnotes:

[1] Peter Johnson, Quarantined: Life and Death at William Head Station, 1872-1959 (Victoria: Heritage House Publishing Company, Ltd., 2013), p.157.

[2] BC Archives, Series GR-2005 – Canada Dept. of Agriculture. William Head Quarantine Station, Annual Report 1917.

[3] Johnson, Quarantined, p.149-150.

[4] Xu Guoqi, Strangers on the Western Front: Chinese Workers in the Great War (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2011), p.55.

[5] Guoqi, Strangers, p.64.

[6] Johnson, Quarantined, p.157.

Primary author: Kate Riordon