William Head Quarantine Station

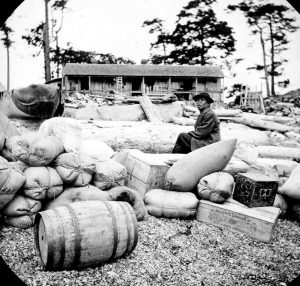

A supply ship has just dropped off that month’s supplies to the Leper Lazaretto. Image F-05162 courtesy of the Royal BC Museum and Archives.

William Head Quarantine Station, located south-west of Victoria in Metchosin, was built during the 1880s in response to fears of plague brought by immigrants to British Columbia. With gold prospectors arriving from California and Chinese labourers immigrating to work the railroad, disease was rampant.[1] Similar in function to Partridge Island Station in New Brunswick, William Head was often the first port of arrival for incoming ships to Canada’s west coast. The station inspected those coming ashore for a variety of infectious diseases in an active effort to keep the population healthy. If necessary, doctors at William Head could quarantine up to 800 people comfortably in their 42-building, 106-acre facility.

The Quarantine Station also served as the main office for the D’Arcy Island Leper Lazaretto from 1891-1924. The station closed in 1959 and the site now serves as a minimum security federal penitentiary.

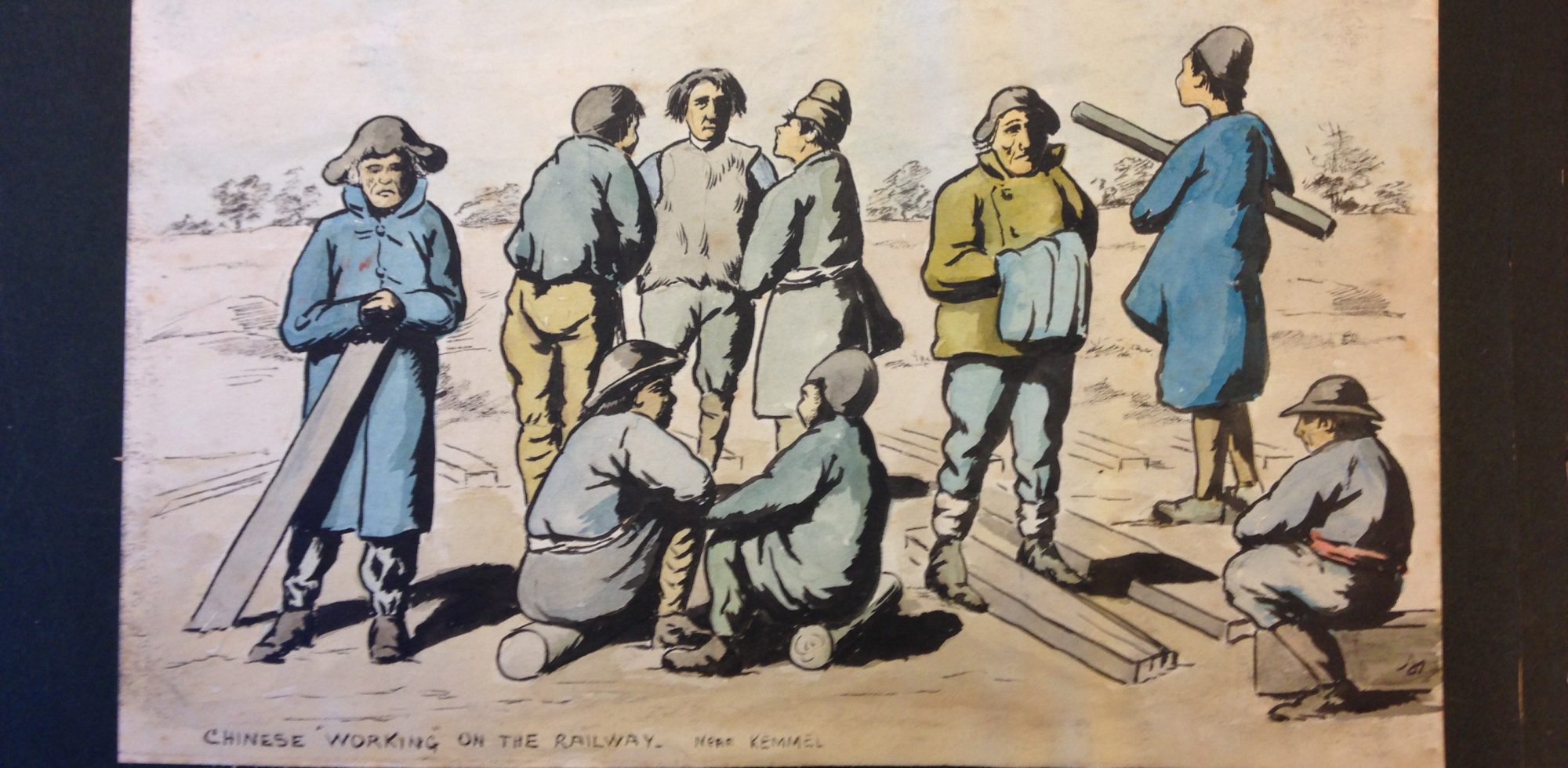

Arrival of the Chinese Labour Corps

By 1917, the British Army was facing a dire labour shortage on the front lines in France. They had not accounted for the amount of labour that would be needed to maintain trench warfare so began recruiting non-combatant workers from China to supplement their ranks. Basing their operations out of Hong Kong, the British began sending recruits across the ocean to Canada, where they would traverse the continent by train before continuing on to France by ship.

The bell tents that housed the CLC at William Head’s “Coolie Camp” from 1917-1920. Image B-01622 courtesy of the Royal BC Museum and Archives.

The Empress of Russia, the first ship of CLC labourers, arrived at William Head on 2 April, 1917 and carried more than 2,000 Chinese.[2] Dr. Rundle Nelson, the director of William Head, quarantined the ship and held them for 2 weeks because of fears of smallpox driven by racialized conceptions of uncleanliness. As ships continued to arrive at the station wharf, the William Head staff and the 5th British Columbia Company of the Royal Canadian Garrison Artillery created a joint-effort “Coolie Camp” where the Chinese were kept under guard.[3] It was difficult for men accustomed to the space and freedom of Mongolia and northern China’s plateaus to live in such constrained quarters, but they were kept busy maintaining vegetable gardens, chopping wood, doing laundry, parading, and digging practice trenches. Members of the CLC also made their traditional crafts and often gifted them to the station’s employees and their families, or even sold them to Victoria socialites.[4]

Life was not easy for anyone at William Head during this period of adjustment. The station director’s records from 1917 show that there were unusually high volumes of rainfall that year which flooded the poorly insulated “Coolie Camp” and kept ships from unloading their cargo, forcing the men to remain on board.[5] Despite the military presence, the Chinese often snuck out of camp to pilfer wood and stones from nearby storage sheds and walls to prop their tents up out of the mud. Eventually a proper drainage system was established that not only helped the “Coolie Camp”, but also solved William Head’s water main problem as well.

After the war ended and the CLC returned to William Head on their journey home, they discovered that the station had undergone a massive renovation; the “Coolie Camp” was now reinforced by fences topped with barbed wire, armed military guards, and even a gunship that patrolled the coast.[6] As the CLC had seen the breadth of Canada twice now, the BC government was adamant that no returning CLC members would be tempted to remain in the province.

William Head and Victoria

Because of worries that the allure of Victoria’s Chinatown would prove strong to the CLC, the 5th British Columbia Company was brought in and extensive measures were taken to keep the CLC at William Head as removed from the city as possible. Large numbers of Chinese workers who had worked on the Canadian Pacific Railway and were prospectors during the Gold Rush had settled in Victoria, inciting panic and rampant racism among the city’s white population.

A CLC man stands on the wharf of William Head with his kit bag, 1917. Image B-01618 courtesy of the Royal BC Museum and Archives.

William Head Station became an important facility to manage the “uncleanliness” of Chinatown; those who had diseases like leprosy were quickly annexed to the station and abandoned on D’Arcy Island. With several thousand Chinese milling about a scant 14km from Victoria, waiting for ships to take them back to China, tensions ran high and discipline was swift. When a local Victoria baker helped smuggle a Chinese man out of William Head, both were quickly arrested. While the local man was acquitted of his charges, the man he helped escape was sent back to William Head and placed on the next ship back to China.[7]

During its time of active service during the war, William Head was more like a prison than a quarantine station. Highlighting the worst aspects of racial discrimination, it did everything it could to keep the Chinese held there far from Canadian society, but it also kept most of the operation a tight secret. While the official reason was to keep the Germans from getting wind of Britain’s plan, secrecy was also necessary to keep BC’s white population calm.

The staion’s war effort involvement ended abruptly; a small note in the 1920 Annual Report for William Head states simply that “On April 4th the last of the Chinese Coolies embarked for China on the SS “Bessie Dollar,” and the Coolie Camp was dismantled and finally closed on April 17th.”[8]

Dr. Geoffrey Bird, War Memories Across Canada Project (Royal Roads University, Victoria BC), accessed November, 2016.

Footnotes:

[1] Peter Johnson, Quarantined: Life and Death at William Head Station, 1872-1959 (Victoria: Heritage House Publishing Company, Ltd., 2013), p.9-10.

[2] Xu Guoqi, Strangers on the Western Front: Chinese Workers in the Great War (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2011), p.56.

[3] “Quarantine was hell at William Head; Chinese men recruited by Britain for ‘non-combatant’ roles in First World War,” Times-Colonist, May 29 2016, Islander section, D4.

[4] Johnson, Quarantined, p.152.

[5] BC Archives, Series GR-2005 – Canada Dept. of Agriculture. William Head Quarantine Station, Annual Report 1917.

[6] Johnson, Quarantined, p.155.

[7] Ibid, p.155-6.

[8] BC Archives, Series GR-2005 – Canada Dept. of Agriculture. William Head Quarantine Station, Annual Report 1917.

Primary author: Kate Riordon