Since their first arrival in Canada in the 1800s, Chinese Canadians were met with discrimination because of their racialized status. Racialization is an arbitrary process whereby certain phenotypical, physical, or cultural differences are given a certain meaning of difference, typically negative and exclusionary.[1] Even though BC colonization has been linked to China since the first otter pelt trade in the 1700s, Chinese migrants have been perceived as the ‘other’ which threatened the success of English-speaking colonization in the province.[2] By the 1885 Commission on Chinese Immigration, the categories of Canadian and Chinese were fixed as mutually exclusive.[3] By the 1920s, the reasoning for the exclusion and different status of Chinese Canadians rested on 4 claims:

- Chinese civilization was fundamentally different from that of Europe and Canada

- The character of the ‘Chinese’ was fixed and unchanging

- Chinese could not be assimilated into Canadian culture

- The presence of ‘Chinese’ threatened Canadians

These ideas of unassimilability and binary difference between Chinese and Europeans was visible in many arenas of interaction, but was most notable in economic concerns and immigration practices. These ideas were influential across Canada, not only in Victoria, and because they were often built gradually and over time, it is difficult to find specific sources that discuss these issues in the World War I time frame in Victoria.

Economics

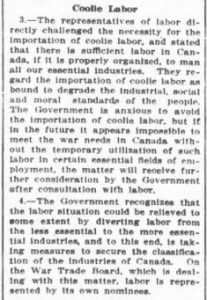

As the federal government struggled to decide how to fill the labour shortage in Canada in the last years of the war, the idea of ‘coolie labour’ was resoundly rejected because of the “industrial, social and moral standards of the people.” Source: Daily Colonist, 15 February, 1918, pg. 1.

While the 1910s were a period of overall success for merchants and labourers in Victoria’s Chinatown, jobs, wages, and working conditions were a point of contention between Chinese Canadian workers and Anglo-Canadian labourers and employers.

Pre-World War I

Prior to World War I, anti-Asian labour sentiments increased drastically. In 1906, the Canadian Trades and Labour Congress met in Victoria to lobby against Asian labour, and in 1907, the Asiatic Exclusion League was founded in Vancouver to protest the increasing Asian immigration.

In 1907, this tension culminated in a night of rioting by Anglo-Canadians in Vancouver’s Chinatown and Japanese neighbourhood.[4] While 1908-1913 was a boom period in BC’s economy, there was no place for Asians in the “white man’s country.” Rumours and stereotypes of cheap Asian labour raised ire among labourers who felt their jobs were being stolen by Chinese, and Japanese, Canadians who were unassimilable in Canada.[5]

During the war years

During the 1910s, Chinese Canadians were prohibited from many occupations since their names were not included on the provincial voters list – a requirement for some jobs like lawyers and doctors.[6] They were also informally excluded from industries like forestry, mining, fishing and public works projects that received government funding.[7]

Many Anglo-Canadian employers refused to hire Chinese Canadians, and Anglo-Canadian unions excluded them from their organizations. Likely, it would have been smarter for Chinese Canadians to be included in union activities, since employers often reverted to Chinese Canadian labour when their other employees walked out.[8] When coal miners in Nanaimo and across the island walked out from the Dunsmuir Mines in 1912-1913, mine owners hired Chinese labourers as strikebreakers until the 88th Victoria Fusiliers were sent in to restore order and the strike was broken in 1914.[9]

During the war, some of the strong anti-Asian sentiments from earlier decades was reduced, but anytime Chinese Canadians competed for Anglo-Canadian jobs or importing them was considered to fill labour shortages, the “Asian question” or “Oriental Problem” was vehemently brought up.[10]

Immigration

Like economic discrimination, during the 1910s there was little change in the immigration restrictions for Chinese Canadians but they were highly affected by earlier policies and legislation. First established in 1884, the most notable piece of anti-Chinese immigration legislation was the head tax, which weant through many iterations:[11]

- 1884 – first head tax established at $10 per person

- 1886 – head tax was raised on January 1st to $50

- 1900 – the head tax doubled to $100

- 1904 – the price of the head tax peaked at $500 per person

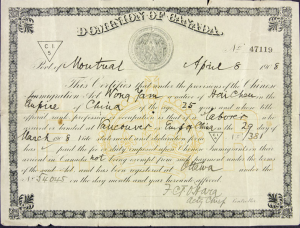

A sample head tax certificate. On this document, a Chinese Canadian man landed at Vancouver in 1908 and would have had to pay $500. Source: Library and Archives Canada, Leung Doo Wong fonds.

Between 1907-1915, 28,612 Chinese immigrants entered Canada paying the $500 head tax, raising a revenue of $14,355,406, half of which went to the provincial government. The $500 head tax kept out large numbers of Chinese immigrants, but following the 1907 riot, increased restrictions were felt to be needed.[12] In 1908, the government increased the amount of money Chinese immigrants had to have in their pocket upon arrival, in addition to the head tax fee, from $25 to $200.

In 1913, further restrictions were passed that limited the numbers of skilled and unskilled labourers arriving in Canada.[13] That year, the Canadian government also began negotiating with China to remove the head tax system entirely and replace it with a quota system, similar to what was in place with Japan. However, the outbreak of World War I cut these negotiations short and immigration laws remained relatively static until 1923, when Chinese immigration was stopped completely.[14]

Repealing discrimination

This immigration ban remained in place until 1947, when it was finally repealed and immigration from China slowly began again. In 2014, the BC government apologized for the “historical wrongs” committed against Chinese Canadians by previous provincial governments in an effort to recognize the substantial social, cultural and economic contributions of Chinese Canadians.[15] In 2006, the Canadian federal government also apologized to the Chinese Canadian community specifically for the head tax.[16] While apologies do not reverse what happened in the past, they mark an important an important step in knowing and acknowledging the past.

Footnotes

[1] Timothy Stanley, Contesting White Supremacy: School Segregation, Anti-Racism, and the Making of Chinese Canadians (Vancouver ; Toronto: UBC Press, 2011), 8.

[2] Stanley, Contesting White Supremacy, 53-54.

[3] Stanley, Contesting White Supremacy, 78.

[4] Charles Sedgewick, “Context of Economic Change and Continuity in an Urban Overseas Chinese Community,” 1970, CA UVICARCH AR113, University of Victoria Special Collections and University Archives, https://dspace.library.uvic.ca//handle/1828/3216, 123.

[5] Patricia E. Roy, A White Man’s Province: British Columbia Politicians and Chinese and Japanese Immigrants, 1858-1914 (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2014), ProQuest ebrary, 229-230.

[6] David Chueyan Lai, Chinatowns: Towns Within Cities in Canada (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2000), ProQuest ebrary, 216.

[7] Roy, A White Man’s Province, 243.

[8] Lai, Chinatowns: Towns Within Cities in Canada, 218.

[9] Lynne Bowen, “Vancouver Island Coal Strike,” The Canadian Encyclopedia, http://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/vancouver-island-coal-strike/ (accessed December 3, 2016)

[10] Patricia E. Roy, The Oriental Question: Consolidating a White Man’s Province, 1914-41 (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2014), ProQuest ebrary, 24.

[11] Jin Tan and Patricia E. Roy, The Chinese in Canada, Canada’s Ethnic Groups (Saint John, N.B.: Canadian Historical Association and Keystone Printing & Lithographing, Ltd., 1985), http://www.collectionscanada.gc.ca/obj/008004/f2/E-9_en.pdf, 8.

[12] Sedgewick, “Context of Economic Change and Continuity in an Urban Overseas Chinese Community,” 122.

[13] Sedgewick, “Context of Economic Change and Continuity in an Urban Overseas Chinese Community,” 125.

[14] Roy, A White Man’s Province, 237.

[15] “Chinese Legacy BC,” Province of British Columbia, http://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/governments/multiculturalism-anti-racism/chinese-legacy-bc (accessed 20 November, 2016).

[16] Campbell Clark, “PM offers apology, ‘symbolic payments’ for Chinese head tax,” The Globe and Mail, http://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/national/pm-offers-apology-symbolic-payments-for-chinese-head-tax/article711245/ (accessed 20 November, 2016).

Primary author: Kate Siemens