The period leading up to WWI was fraught with conflict and strife between Indigenous peoples and settlers.

The outbreak of smallpox carried by infected Europeans through Fort Victoria decimate Island Indigenous populations. This epidemic carried on for two years, sparking the Tsilhqot’in War (1864). The conflict ensued in attempt to stop the construction of the Caribou Wagon Road and prevent the movement of settlers carrying smallpox. [7]

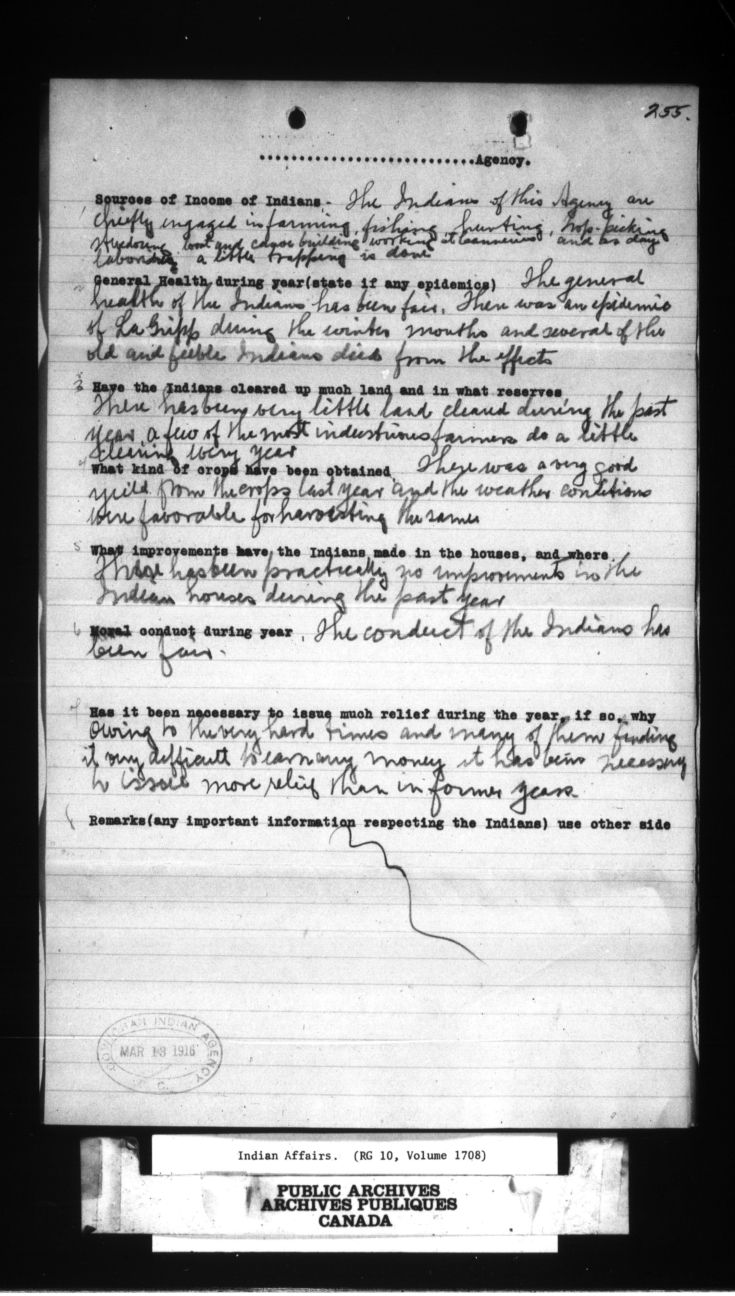

Central to the reason behind the broken relationship between Indigenous Nations on Vancouver Island and colonial authorities was the question of land use rights. Prior to the war, the ability to utilize the land for subsistence was rapidly decreasing.

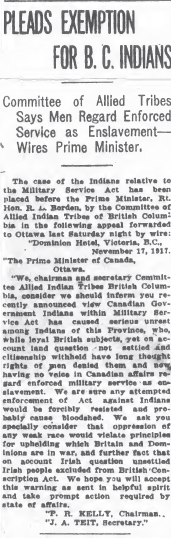

In British Columbia, irreconcilable treaty issues were exhibited by low enlistment rates. Dissension transformed into collective organization with the formation of the Allied Tribes of BC.

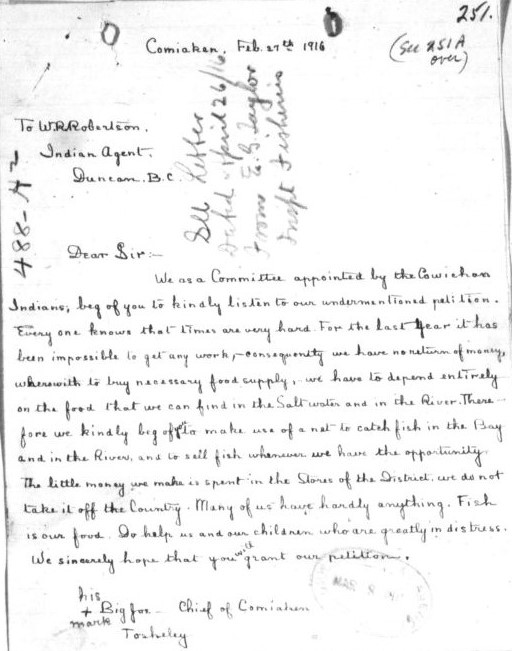

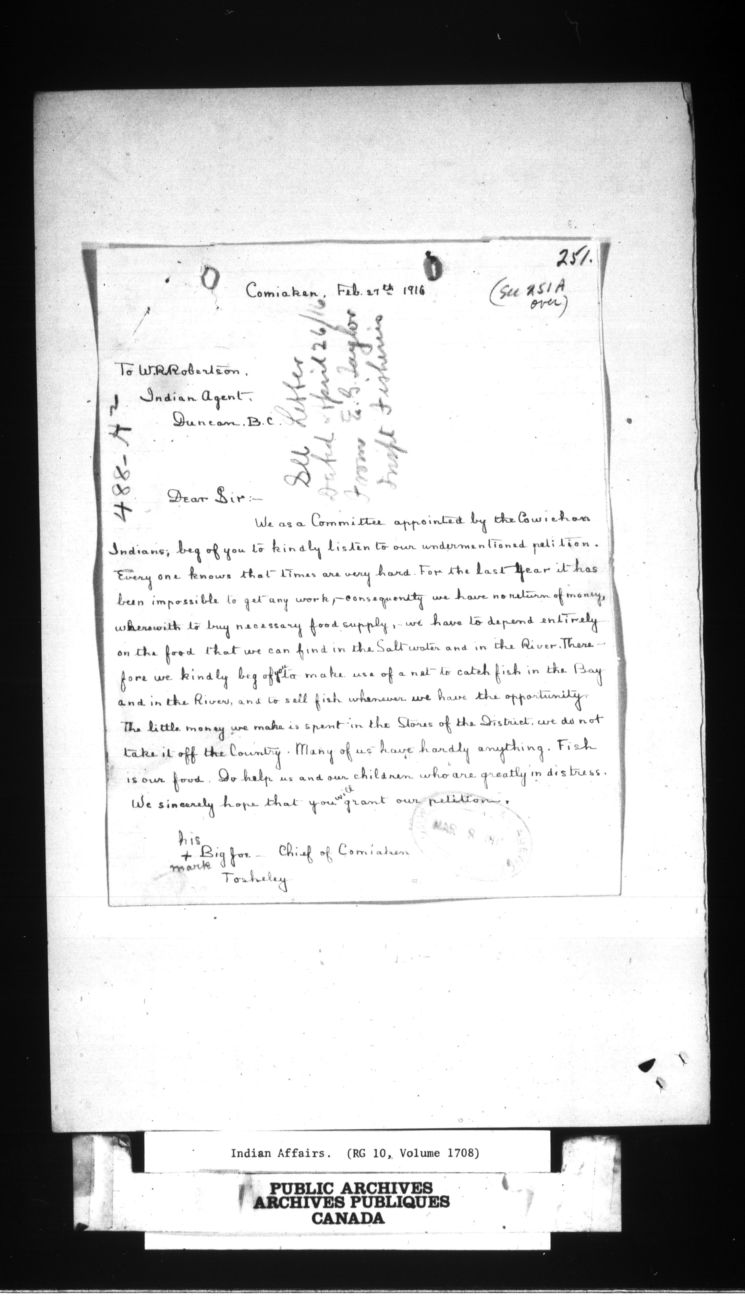

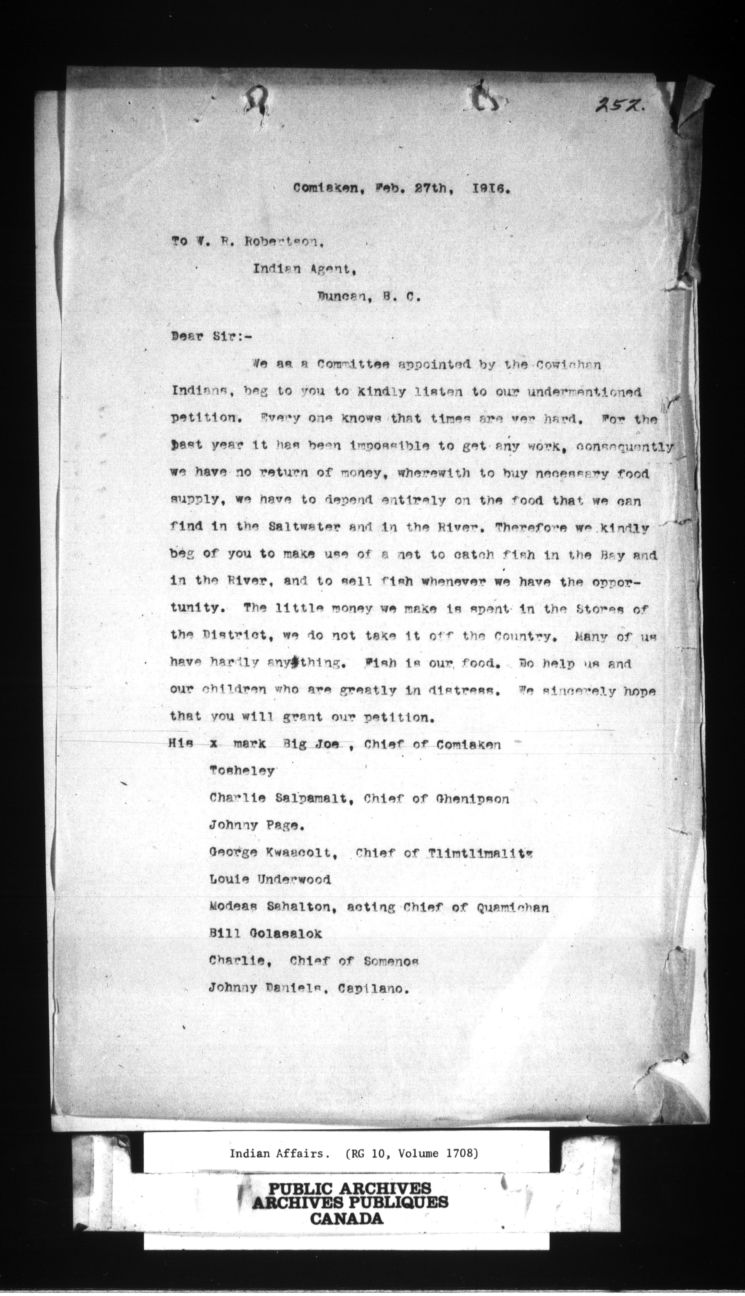

This plight of the Island’s Nations peoples during the 1900s was highlighted in a letter from a number of Vancouver Island Nation Chiefs who said “for the last year it has been impossible to get any work, consequently we have no return of money, wherewith to buy necessary food supply, we have to depend entirely on the food that we can find in the salt water and in the River. Many of us have already anything. Fish is our food.

Conscription:

“Indians [in] this province who while loyal British Subjects yet on account of land question not settled and citizenship withheld, have long thought rights of man denied them and now having no voice in Canadian affairs regard enforced military service as enslavement.”

– P.R. Kelly, Chairman & J.A. Tait, Secretary.

Silent protest became more vocal during the height of the conscription debate at the beginning of 1917. In August 1917, the Military Services Act instituted conscription; military service for all British subjects eligible to serve was mandatory. The draft didn’t make an exception for Treaty ‘Indians’ who presumed that they would be exempt because they didn’t have the same rights that were afforded to Canadians.3]

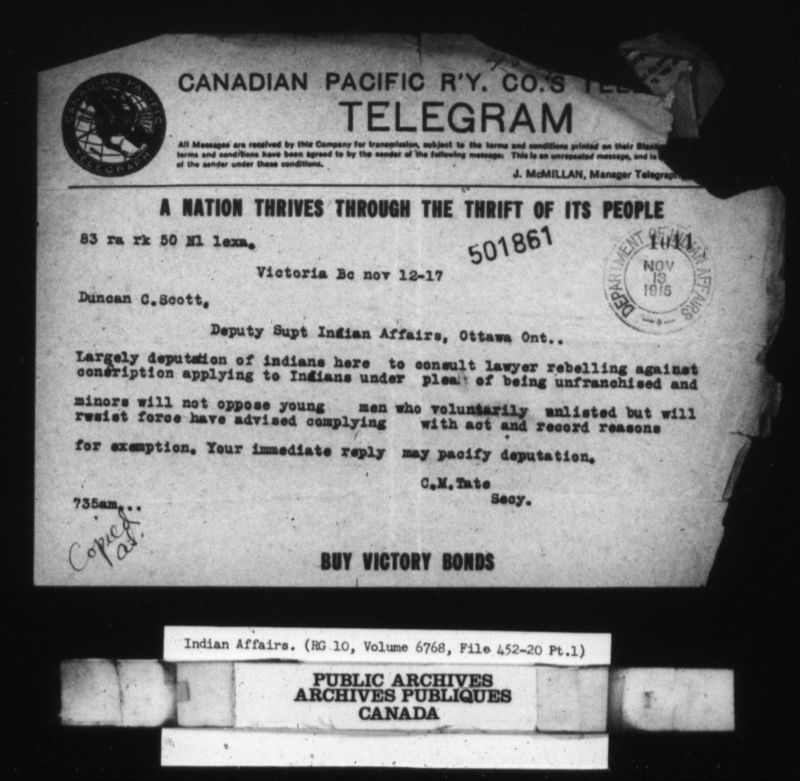

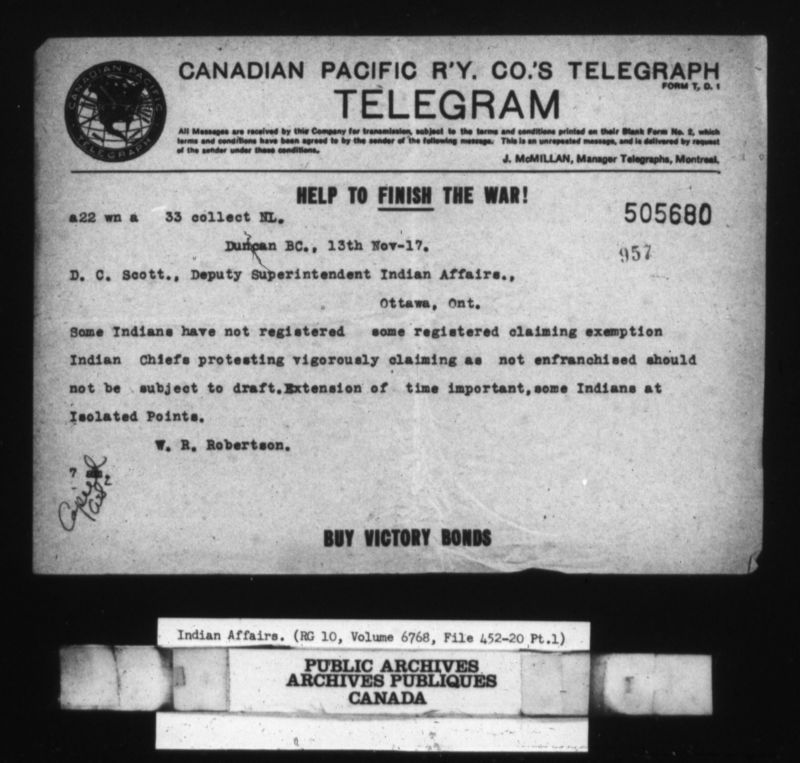

It was not long after that the Indigenous Nation leaders across Canada united to protest the decision, because conscription was a fundamental violation of their treaty rights. [4] Unity between Nation leaders occured on Vancouver Island; a British Colonist article stated that in Nov 1917, “a “number” of Indigenous chiefs from the East Coast met with legal authorities.

As a result of protest from Indigenous Nations, many non-Aboriginal people publicly supported the exemption of status Indians from conscription.

On January 17, 1918, an Order-in Council (PC 111) was passed that officially exempted status Indians from performing combatant duties but they could still be called to perform non-combat roles in Canada.[5]

Telegram to D.C Scott, 1917 from Indian Agent W.R. Robertson