Despite the war’s end in November of 1918 conditions didn’t immediately improve for workers. The economic concerns and social strains that had marked the later war years didn’t simply disappear. Agitation had been building for years. The economy had improved, but not for everyone. The Mathers Commission, ordered to look into working conditions in 1919, was told by one carpenter that no serious construction had occurred since 1915. Prices for food increased alongside the numbers of unemployed as soldiers returned home, competing with those who had replaced them at work. Women in particular were effected, as they were treated as merely a stopgap measure by most employers1. Returning soldiers were both a boon and a problem for organized labour. Some joined in the strikes that wracked the province, like the Consolidated Whaling Corporation employees who walked out on April 17th, 19192. Many were from working class backgrounds, and felt sympathy for the strikers3. Others had no such feelings, such as those who organized themselves into vigilante groups to attack socialists in Winnipeg4.

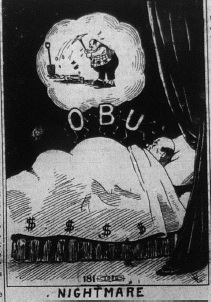

Although the east/west division within the Trades and Labour Congress can be easily overstated, in late 1918 there was a palpable split. Industrial union agitation had clashed with conservative craft unionism since the beginning of the war. The Bolshevik Revolution had invigorated Canadian radicals, but it had disturbed their more conservative counterparts. At a convention of the Congress at Quebec in 1918, western radicals had their proposals almost consistently shot down in bitter debates within the convention. Samuel Gompers, the head of the AFL, was on Parliament Hill shortly before attacking “the Bolsheviks and the Hun” while western socialists expressed their sympathy with the Russian revolutionaries5. The snub that the western delegates perceived led to a split, and the creation of a separate Western Conference to deal with some of these issues. The VTLC president was an internationalist named Eugene Woodward, who had beaten out the longshoreman Joe Taylor in January 1919. Woodward would end up being unfavorable to the OBU movement because it wasn’t sanctioned by the “International” as a whole6. However, the Western Labour Conference held in Calgary was chaired by Taylor, not Woodward. Woodward was “noticeably absent” when the conference approved the creation of “One Big Union” to organize a “dictatorship of the proletariat”. They also approved a list of demands, foremost of which was a six-hour work day and only five days of work a week, with a general strike planned for June 1st to try and enforce these demands. Over April, unions across the country had to vote on whether or not to join the OBU in its strike. In Victoria, partially due to the efforts of locals like Joe Taylor, sentiment was very positive. However, there were many notable sources of opposition from inside and outside the labour movement7.

Gregory Kealey reports that the Victoria sympathy strike ran from June 23rd to July 7th, with around 5,000 workers participating8. However, the Victoria Trades and Labour Council was highly reluctant to throw its weight behind the OBU. When the referendum was called, the union locals were split thirteen in favour, fourteen against. This was not a complete measure of support one way or another, at least based on pure numbers. Almost all of the shipyard workers were in favor9. Three quarters of Victoria’s 7000 union members were involved in the shipyards, and 2300 of them belonged to the Shipyard Laborers, Riggers and Fasteners alone10. No single union in Victoria could match their numbers, but groups like the Street & Electric Railways or Fireman’s unions had a particular influence that the Shipyard Labourers lacked.It was the Metal Trades Council that put the most weight behind the OBU sympathy strike, not the VTLC. During a mass meeting in the Royal Athletic Park, the Metal Trades Council put forward and passed a resolution calling for the resignation of the entire federal government. The resolution read in part that “we, the workers of Victoria in mass meeting assembled, do hereby call upon the Trades and Labour Congress to demand the resignation of the Federal Government in order that the people may have an opportunity to register their opinion of the war time profiteering and class legislation which has disgraced its term of office”. This motion was seconded by Eugene Woodward, whose dislike of the OBU was over doctrine, not its end goals11.

However, this meeting wasn’t enough to actually sway the various councils to strike, but on June 15th the 1400 strong Carpenter’s Union came onside with the strike. The Victoria Strike Committee, the body that was theoretically meant to stand for all workers in Victoria on the issue, was dissolved on June 17 due a split decision amongst its members. Despite the lack of official direction, workers in Victoria still acted on behalf of the larger movement. Longshoreman refused to move cargo bound for Vancouver, which was already bound up in its own sympathy strike12. The strike in Victoria only lasted a short time. On June 21st, Winnipeg strikers came under assault from elements of the RNWMP and the Canadian militia. The Metal Trades Workers in Victoria finally acted on the calls to strike, walking out at 10 a.m. on June 23rd. The civil unions, streetcar workers, electrical workers and other remained on the job13. According to John Chrow, the Labour Gazette correspondent in Victoria, “all shipyards and iron foundries [are] without exception closed”14. For all of the build up that led to it the strike was short lived and didn’t have the desired effect, partially due to the lack of support from outside the Metal Trades unions, but it was also due to the nature of the strike itself. Victoria was showing solidarity with a fight that had its origins elsewhere. Although the strikers in Victoria had their own demands, their main impetus was the fight in Winnipeg. That strike was called off shortly after Victoria workers walked out. without that motivation, the Victoria strike quickly lost steam. Within a few days, everyone was back at work. The AFL re-elected Samuel Gompers, whose influence was directed against the OBU. The OBU fell out of favour under the ideological assault be the AFL and TLC and its own failure in Winnipeg. As its support fell away Victoria organizations like the VTLC and Metal Trades Councils were taken over by more conservative members15. Although radicals were still active, their moment had passed and they were relegated to the background.

[1]Isitt, Benjamin “Searching for Workers’ Solidarity: The One Big Union and the Victoria General Strike of 1919″, Labour/Le Travail, Vol. 60, (Fall, 2007) pp. 9-42, 13

[2]BC Archives,GR-1695, B07137 T-2697

[3]Seager, Allan, Roth, David, “British Columbia and the Mining West: A Ghost of a Chance” in The Workers Revolt in Canada, 1917-1925, ed. Heron, Craig, University of Toronto Press (Toronto, 1998), 275

[4]McCormick, Ross A. “Reformers, Rebels and Revolutionaries: The Western Canadian Radical Movement 1899-1919”, University of Toronto Press (Toronto, 1991), 161

[5]McCormick, 147-149

[6]Isitt, 17

[7]Isitt, 20-22

[8]Kealey, Gregory S. “Workers and Canadian History”, McGill-Queen’s University Press (Montreal and Kingston, 1995), 306

[9]Seager, Roth, 251

[10]Isitt, 16

[11]BC Archives, GR-1695, B07141 Roll T-2701

[12]Isitt, 31

[13]Isitt, 33-35

[14]BC Archives, GR-1695, B07141 Roll T-2701

[15]Isitt, 35-39

By Connor McLeod