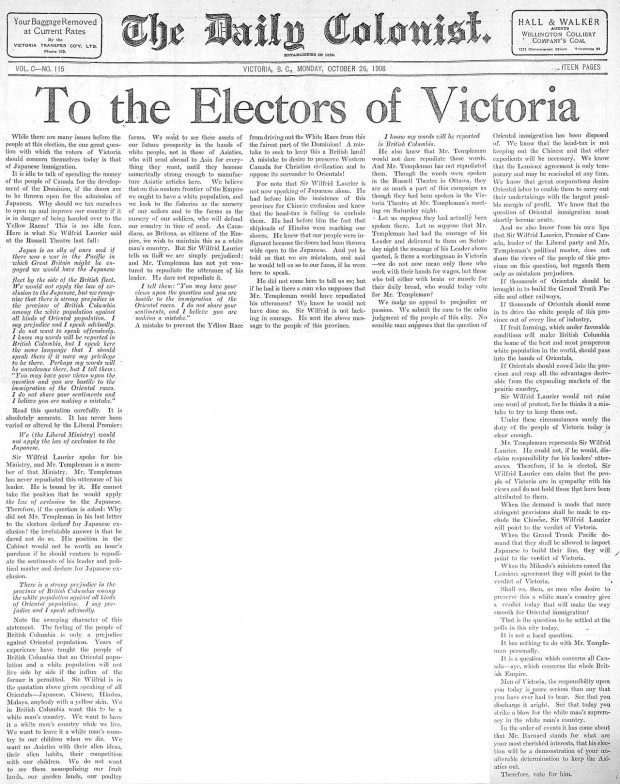

The union movement on the west coast was predicated in part on racial exclusion. This was one part racial prejudice, one part economic exclusion. Craft unions generally ignored the less skilled workers, who were frequently non-British immigrants. Chinese and Japanese workers seem to have taken the brunt of it, but First Nations, Finns, Italians, Ukrainians and others were all subject to various forms of racial discrimination. Asian immigrants were generally seen as the least assimilable, and many people held that they were inherently outsiders who could not and would not adapt to their new home1.

The Japanese, even in the First World War, were seen as a potential imperial threat. Early in the war Japan was an ally, and actually provided ships to guard BC’s coast. This didn’t stop members of government, and members of the labour movement, from publicly questioning their intentions2. However, public opinion waxed and waned on the Japanese specifically, although they were frequently lumped in with the Chinese as homogenous “oriental labour”. The fishing and canning industry was the site of the most pronounced conflict, as Japanese workers accounted for a significant portion of the workforce. They were accused of undercutting both white and First Nations fishers and labourers, while the cannery owners were accused of favouring the Japanese. There wee accusations that a proposal for a Japanese battalion was shot down due to lobbying from cannery owners who didn’t want their cheap labour being shipped to fight in France 3.

The Chinese were seen as less of an organized threat and more as an economic and social problem. Many were immigrants or descendants of immigrants who had come over in the 1880’s to work on the railway. This was an early source of tension between labour activists and Chinese immigrants. Labour groups like the Knights of Labour resented the Chinese, whom they saw as direct competition. When the CPR was completed, many workers returned to China, but a large number stayed4. The 1911 census listed 3,458 Chinese residents in Victoria, only 253 of whom were women5. During the war, activists in both Victoria and Vancouver tried to introduce “white worker only” clauses to the licenses of hotels in order to free up space in the workforce for white women. While this was shot down in Victoria, the licensing commission in Vancouver began denying renewals to businesses employing “asiatics” in 19166.

European immigrants were subject to discrimination as well. Germans and Austrians became enemy aliens. other, less well known groups like the Finns and the Ukranians were also subject to discrimination, on a racial as well as national basis. This was less important in Victoria than in other parts of Canada, but Victoria still saw some public, intense instances of discrimination. Furthermore, the minutes of the Victoria Labour Council show a preoccupation with addressing the problem of “alien labour”–a term commonly referred to the problems posed by non-white (typically Chinese or Indian) workers. Motions seeking to address alien labour were put forward at nearly every one of the Victoria Labour Council’s bimonthly meetings. At a July 2, 1914 meeting, for example, a motion was put forward calling for an end to discrimination of any working man “provided he is of the white race”.

Outside of membership to radical organizations, most minority groups were forced to form their own unions. Chinese unions sprang up throughout the early 20th century as a response to their exclusion from white unions7. Anti-Asian sentiment was particularly vocal on the West Coast, and it carried over into the labour movement. Unions were in the peculiar situation of creating their own strikebreakers by keeping Chineses and Japanese workers on the outside.

[1]Roy, Patricia E. “The Oriental Question: Consolidating a White Man’s Province, 1914-41″ UBC Press (Vancouver, 2003), 31-32

[2]Ibid,14-15

[3]Ibid, 21-22

[4]Roy, Patricia E. “A White Man’s Province: British Columbia Politicians and Chinese and Japanese Immigrants, 1858-1914″ UBC Press (Vancouver, 1989), 58-62

[5]Lai, David Chueyan “Chinatowns: Towns within Cities in Canada” UBC Press (1988, Vancouver), 200

[6]Roy, The Oriental Question, 17-18

[7]Creese, Gillian “Organizing against Racism in the Workplace: Chinese Workers in Vancouver Before the Second World War” Canadian Ethnic Studies/Etudes Ethniques au Canada Vol. 19 No. 3 ( January 1987), 35-46, 40