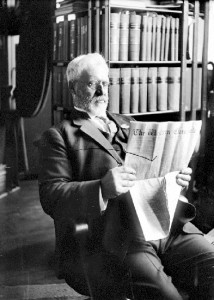

The antithesis of McBride, John Oliver had little education, spoke with a thick Derbyshire accent, and took pride in his simple, farming background. This seemed to appeal to the populace though, as his lack of pretense would alleviate some of the growing disillusionment with the government. Taking on the role of premier in early 1918, Oliver could not have known that the labour movement was about to come to a boil under his leadership.

Before Becoming Premier

Winning a seat for himself in the 1916 provincial election, Oliver was then appointed by Brewster to the agricultural and railway departments.[1] Owning and developing agricultural land himself in Surrey, Oliver took great pride in this particular department and even developed the Land Settlement and Development Act.[2] This act, as the title alludes to, would enable returning soldiers to settle on and develop agricultural land in British Columbia which he viewed as vital for the province’s future. He also had a large burden to bare in the department of railways which the McBride government left him, but that’s a story for another time. Oliver’s devotion to his job and the province clearly set him apart from other candidates in 1918, for he was elected by his peers to lead the Liberal party after Brewster’s untimely death.

The Troubles Begin

1918 would hold more surprises. The labour movement would erupt into several strikes in August, including street railwaymen, civic employees, the Federation of Labour, and other radical Socialist movements.[3] August 2 heralded the first General Strike in Canada to honour the memory of Ginger Goodwin, a socialist leader who was killed by the RCMP near Comox.[4] The Victoria Colonist described the striker’s actions as “treasonable” and “unpatriotic”, while returned, wounded soldiers found little sympathy for the death of a draft dodger.[5] This was not the only strike of 1918. In fact, around Victoria at least, the number of strikes and lock-outs had increased significantly from the previous year. Victoria, in 1917, had seen at minimum four main strikes through the year, in 1918, the city witnessed 10.[6] Two of which (the Street Railway workers and the Electrical workers strike) reached farther than Victoria. Although these strikes eventually fizzled out, the socialist rhetoric would be firmly planted in the minds of many labourers in the big cities across BC to the displeasure of John Oliver and his government.

The war was soon over by early November and Canadian soldiers were returning from France to a country which had changed from the pre-war years. Oliver’s hope to settle soldiers on agricultural land ended in disappointment, for it seemed not many veteran’s had plans to change their livelihoods from the pre-war period.[7] The majority of returning soldiers went back to the cities to find work in industries, which they could not find. The war had had a great impact on industries in Victoria, as the need for continuous supplies for the Western Front inflated the need for labour in manufacturing.[8] With the war over, most industries (with the exception of logging and shipbuilding) were firing rather than hiring as the market for their goods ceased to exist.[9] Legislation by the Liberal government had previously given women in the workplace a minimum wage, and set the work day at a maximum eight hours for some industries.[10] Though this was progressive, it did not solve future issues created by an influx of workers. The government had done little to alleviate the effects of the post-war job market, so unrest was brewing in an already tumultuous stew.

John Oliver, though a Liberal in practice, had little sympathy for soldiers and other labourers who found themselves in a jobless situation.[11] Had he not offered returned soldiers ample opportunity to buy cheap land and sow profit off it? He believed it was not his fault that they decided not to make use of this generous offer. Labour leader and veterans would have been right to assume the premier took British Columbia’s social and economic situation for granted. But Oliver had no patience for socialist thought, and less sympathy for the none-too-well-off. The working (or in this case, not working) class had simply not toiled hard enough, nor had they saved their earnings fervently, so they should not be blaming their society for their problems. This placed him in direct opposition to those taking part in the General Strike of 1919.[12]

Socialist party leaders had promoted the idea of combining craft unions into the One Big Union, and elsewhere lumber, farming, and mining unions united for a sympathy strike.[13] The great General Strike of 1919 was underway. Even soldiers joined the cause in protest of Canadian expeditionary forces being sent into Vladivostok despite the official end of hostilities by the end of 1918. The first few soldiers to come back from this expedition arrived in Canada by early May 1919 – full of complaints.[14] Conflict and Communist thought seemed to be as contagious as the Spanish Flu, and the only thing Oliver could do was hope the strikers’ fever would run its course by the next election.

Lessons Learned?

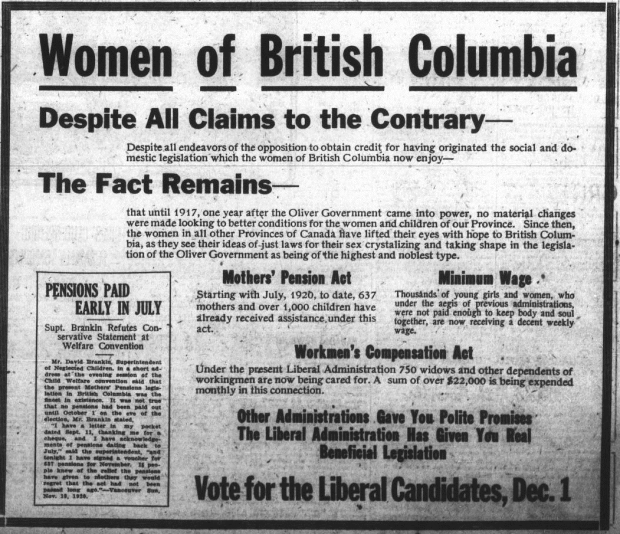

The story ends (the term here is used loosely, for history never actually ends) in 1920, when the next provincial election came about. Oliver knew he was facing dire straits due to the controversies of the last couple years. Not only had he not called an election to cement his premiership when he was placed in the position, but last year’s labour strife had weakened the Left’s resolve to vote Liberal.[15] Before the election in early December, John Oliver would go on to “establish mothers’ pensions in 1920, provide maintenance for deserted wives, and improve both health and educational services”.[16] The results were on Oliver’s favour, with twenty-six seats for the Liberals, fourteen seats for the Conservatives, four for Labour, and three going to Independents.[17] It appeared social legislation may have improved his party’s odds at the polls, especially since women were now voting. He later went on to impose more controls on the forest industry, and enforce better regulations for public utilities.[18] Though ardent against Communism, Oliver must have felt government intervention was the most effective way to improve conditions for the provincial populous. The turbulent years of the Great War and post-war period changed the working class’s view of how the government should relate with labour, women, and business, and as a Liberal, Oliver had to keep up.

[1] Victoria Daily Colonist, November 30, 1916, vol. 50, no. 304, 1.

[2] David Michael, “Oliver, John”, in EN:UNDEF: public citation publication, vol. 15, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 20, 2015, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/oliver_john_15E.html.

[3] Ormsby, British Columbia: a History, 400.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Victoria Daily Colonist, August 3, 1918.

[6] BCA, GR 1695.

[7] Mitchell, “Oliver, John”.

[8] Ormsby, British Columbia: a History, 406.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Mitchell, “Oliver, John”.

[11] Ormsby, British Columbia: a History, 408.

[12] British Columbia: a History, 409.

[13] Ibid., 408-410.

[14] Victoria Daily Colonist, May 6, 1919.

[15] Ormsby, British Columbia: a History, 412-413.

[16] Mitchell, “Oliver, John”.

[17] Ormsby, British Columbia: a History, 414.

[18] Mitchell, “Oliver, John”.