On July 5, 1916, Bowser called a provincial election.[1] Despite what the Colonist and Bowser himself thought, the Liberals had everything to gain while the Conservatives had everything to lose. Bold assertions of “financial strength” and “enhanced prestige” under duress did not fool many voters.[2] The Liberal party under Brewster came out on top in a sweeping majority winning 36 of 47 seats.[3] For the first time in forever, the provincial Liberals would be able to pass acts without much opposition.

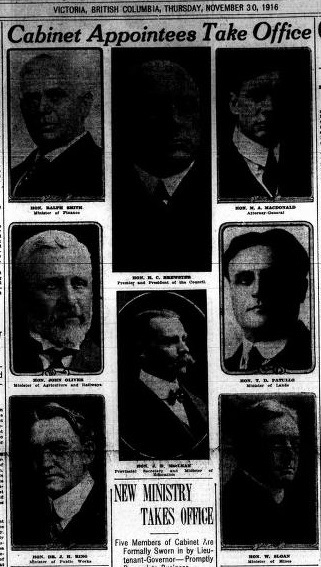

Before Brewster was sworn in as premier of British Columbia on November 23, he “had federal civil service commissioner Adam Shortt [give] advice on the creation of a provincial commission, had an accounting firm review provincial finances, warned of reduced expenditures and higher taxes, and invited women to help purify political life”.[4] Clearly, he was a man on a mission. By November 30, he had appointed his cabinet ministers some of whom included John D. MacLean as Provincial Secretary and Education, John Oliver as Minister of Agriculture and Railroads, and Thomas D. Patullo as Minister of Lands.[5] All would later go on to become premiers themselves. Brewster’s cabinet was evidently very strong, and he would put that strength into use during his all-too-short term in office.

Labour

During a time of strife when prices were rising and Labour was becoming increasingly agitated, Brewster’s government produced progressive legislation to ensure a brighter future for the province. When he took power, British Columbia was beginning to suffer from a man-power shortage due to the war, and the cost of living was rising while wages were stagnant at 1914 depression levels.[6] It is no surprise then that the labour movement had begun to grow. Radical leaders from the Industrial Workers of the World and the One Big Union, among others, were pushing for better working conditions, increased wages, and pressured the government against the conscription of labour.[7] Several strikes occurred around the province during this time which resulted in government intervention – something the labour movement was not too fond of. However, the growing popularity of the Bolsheviks in Russia and the mounting casualty list of soldiers meant very few people outside of labour unions would have been sympathetic to their cause.[8] Hence it was heralded by many that Brewster had done more than enough for workers by creating BC’s first Department of Labour as well as passing a Minimum Wage Act before the winter 1917.[9] The new department and act were just two of the reforms Brewster had in mind of alleviating working conditions in BC. During a time of war when men were leaving the province in droves and major strikes were braking out, the premier took steps to work with labour instead of against it.

Women

Brewster also worked with suffragists to extend the role women played in the province. Women’s suffrage did not even make the front page in the Colonist on April 6th, 1917, and is instead buried on the fourth and seventh pages.[10] The short articles declares that with time, women might be able to keep up with politics such as men have, and perhaps even be ahead of them where household matters are concerned. They go on to say that women, whose sex gives them the natural graces to be morally superior to men, should “elevate politics”. The articles fail to take into account the changing genders roles which had been rapidly occurring, especially during the Great War. Harlan Brewster received a year’s worth of flowers upon his desk and a round of applause from various women’s associations. A few days later on April 12, the Equal Guardianship Act’s second reading made front cover news.[11] The Act made parents equally responsible for the care of their children. As to why it hadn’t been passed before, even Brewster himself claimed not to know as all other provinces had an equivalent act already passed by then. Although the women who campaigned for suffrage during this period would have also claimed that it was for the improvement of their domestic sphere, it is also important to realize that the woman’s sphere of influence had broadened into the work force – something which would later be spurned. (For more information, please refer to Women and Labour).

Death

It is fair to say that in the short expanse of time Brewster reigned as premier of British Columbia, he had made many socially progressive amendments to provincial law. By the end of 1917, Brewster had many more legislative changes he thought to pass before the end of his term, but it was not to be.[12] He was called to Ottawa by Borden for consultation in the winter of 1917, and returning in February, caught “double pneumonia” (lobar pneumonia) and died March 1, 1918.[13] He passed away in Calgary, separated from his family, and was only 48 years old. He left behind four children, and three siblings.

Next: John Oliver

Links

Harlan’s Son, Raymond Brewster

[1] BCA, Microfiche, Victoria Daily Colonist, July 6, 1916, vol. 58, no. 178, 1.

[2] BCA, Microfiche, Victoria Daily Colonist, September 14, 1916, vol. 58, no. 288, 1.

[3] BCA, Microfiche, Victoria Daily Colonist, September 15, 1916, vol. 58, no. 289, 1.

[4] Roy, “Brewter, Harlan Carey”.

[5] BCA, Microfiche, Victoria Daily Colonist, November 30, 1916, vol. 50, no. 304, 1.

[6] Margaret A. Ormsby, British Columbia: a History, (Canada: the MacMillian Company of Canada, 1964): 396.

[7] Ibid., 397.

[8] Margaret A. Ormsby, British Columbia: a History, 398.

[9] Ibid.

[10] BCA, Microfiche, Victoria Daily Colonist, April 6, 1917, vol. 59, no. 100, 4,7.

[11] BCA, Microfiche, Victoria Daily Colonist, April 12, 1917, vol. 59, no. 105, 1.

[12] Ormsby, British Columbia: a History, 398.

[13] BCA, Microfiche, Victoria Daily Colonist, March 2, 1918.