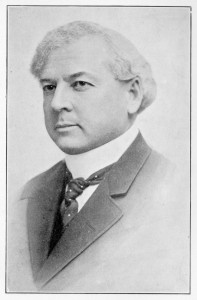

Richard McBride

Sir Richard McBride, premier of British Columbia from 1903 to 1915, is arguably one of the most important persons in the province’s history. His, at times, reckless optimism and abundant enthusiasm for creating a greater province often placed him in precarious situations where thoughtlessness outshone tact. Under his leadership, the province’s attitude towards labour was complicated as it seemed to change as time progressed. His early years in office implied to the provincial populace that he was on the worker’s side.[1] He created ample opportunity in the resource sector for new businesses to open up and employ local workers. This included the salmon industry, which he had previous experience in, the forestry sector, and mining.[2] Additionally, railways, the symbol of progress and the future, would be both his shining glory and an embarrassment. McBride, the epitome of a British Columbian at the turn of the century, held all the qualities that would entail: heartless racism, pro-colonialism, and the belief that provincial resources were inexhaustible.[3] His personality and policies would have a lasting impact, for better or for worse, on the landscape and the people of British Columbia. This short essay, however, is dedicated to McBride and his relationship towards labour around the Great War.

Leading up to the outbreak of war in 1914, McBride had done a good job at keeping the white, male voters complacent with the current government. For example, he had fought for the exclusion of Asian immigrants, effectively ignored Aboriginal land issues, and argued for “Better Terms” for BC under the Dominion Act. Additionally, he kept the forestry industry buzzing with new regulations, and evaporated the province’s debt by 1909.[4] The increasing expansion of big business was practically welcomed by everyone (except the Socialists) until 1913.[5] It was that year in which a recession hit the province, and the once promising future McBride offered seemed to crumble amidst railway scandals, labour agitation, and the premier himself simply becoming old fashioned.[6] He was against women’s suffrage and was an industrial-capitalist and, therefore, an anti-socialist in a province where the British Columbia Federation of Labour (BCFL) had broadened its influence.[7] Moreover, McBride was persistent in his insistence of extending railroads throughout BC despite a large and growing opposition to railways. His moto of Splendor Sine Occasu (“Splendor without end” or “Sunlight without Sunset” in relation to the British Empire) was fitting for the Edwardian era, but would be tested as the century wore on.[8]

The outbreak of the European War in 1914 sent many people from highly diverse backgrounds overseas to serve Britain. Among the reports of increasing tensions between Britain and Germany were tales of espionage and foreign armies lurking to bombard Victoria and Vancouver.[9] The premier, worried about the lack of defensive off the coast of British Columbia, pre-emptively bought two submarines for the price of $1.5 million.[10] They were quickly taken by the Federal government, and placed outside of provincial control.[11] It was only later that questions were asked about why the premier had spent so much upon the submarines without consulting the legislature, but at the time, especially for the civilians of Victoria, people were more concerned about enemy aliens.[12] Persons of Germany heritage, no matter how long they had been a Canadian citizen, were viewed as potentially treacherous, and provincial legislation to intern these “aliens” reflected the insecurities and fears of recession-wartime BC.[13]

As for labourers, they seemed restless over the recent transgressions within the provincial government and the premier had to keep step with them.[14] Unemployment was rampant throughout the province, and McBride, with his lofty and frequent trips to England and haphazard spending, hardly seemed concerned with the province’s suffering.[15] The throne speech in 1915 offered little to alleviate these concerns. There was more talk about railroads to lessen the unemployment problem, but the Conservative government had a long history of corruption with railways, and it was never going to completely solve unemployment.[16] On March 4, 1915, the Coal Mines Regulation Act was passed by the province to ensure better pay and working conditions for miners, but McBride’s eyes were still blinkered solely to railways.[17] There were other issues too which weakened the province’s attachment to Sir Richard McBride. The prohibition and women’s suffrage movements had gained considerable support by 1915, and McBride did not seem to want to move beyond his idyllic, Edwardian world.[18] Nevertheless, it came as a surprise to many when McBride declared that he was resigning in mid-May 1915.[19] Despite his blunders, antiquated ideas, and lack of sympathy for the destitute, McBride was still the face of British Columbia. He left for an agreeable position in London as an ambassador to BC, and his optimistic spirit seemed to leave British Columbia with him.[20]

William John Bowser took over as leader of the Conservatives in the mean time.

Next: Harlan Carey Brewster

-Rachel Bannister

[1] Ormsby, British Columbia: a History, 336-338.

[2] Patricia E. Roy, “McBride, Sir Richard,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 22, 2015,

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ormsby, British Columbia: a History, 341.

[6] Ibid., 363-367.

[7] Ibid., 367-371.

[8] Ibid., 403.

[9] Victoria Daily Colonist, November 28, 1914.

[10] Victoria Daily Colonist, August 6, 1914.

Ormsby, British Columbia: a History, 380.

[11] Ormsby, British Columbia: a History, 380.

[12] Ibid., 382.

[13] Ormsby, British Columbia: a History, 382.

[14] Ibid., 384.

Victoria Daily Colonist, December 4, 1914.

[15] Ormsby, British Columbia: a History, 384.

[16] Roy, “McBride, Sir Richard”.

[17] Victoria Daily Colonist, December 5, 1915.

[18] Roy, “McBride, Sir Richard”.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Ormsby, British Columbia: a History, 390.