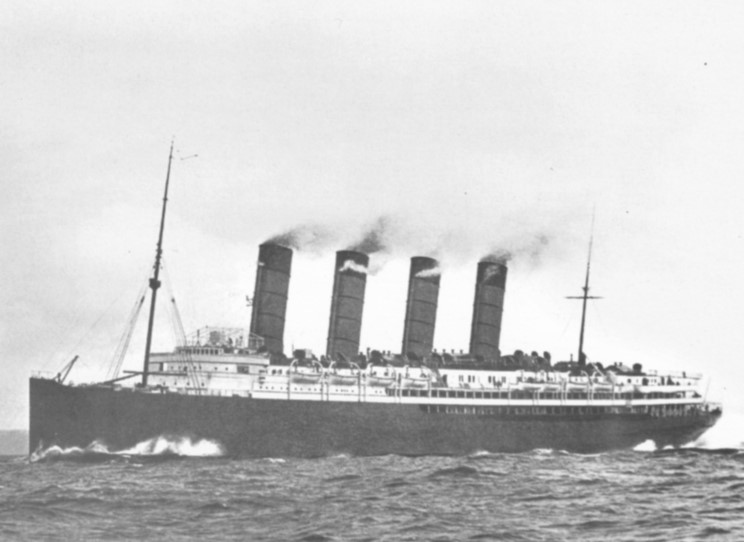

The Cunard Liner Lusitania was one of the world’s largest passenger ships in the early twentieth ship. It’s sinking by a German submarine on May 7, 1915 not only caused the deaths of over 1,400 passengers but also ignited anti-German riots in cities around the world.[1] Victoria was one of such cities that succumbed to violence as mobs wreaked havoc across the city for two days. The Victoria Police Department struggled to control the rioters but the crowds eventually quieted after over 400 soldiers from the 2nd Canadian Mountain Rifles and the 88th Battalion arrived as support.

The Sinking

The Lusitania was traveling from New York to Liverpool when it was struck by a torpedo off the coast of Ireland in the early morning of May 7, 1915. The torpedo struck the bow of the ship and an explosion in the engine room caused the ship to sink in less than 20 minutes. There were 15 Victoria residents aboard the ship including Mr. Cyril Wickings-Smith, the owner of Willows Park Grocery, and his family consisting of his wife, brother, and young son. The Wickings-Smith brothers were traveling to England to enlist in the war effort.[2]

Lieutenant James “Jimmy” Dunsmiur, the son of the Honourable James Dunsmiur and grandson of coal mast Robert Dunsmiur, was also aboard the Lusitania. The Lieutenant had recently resigned as an officer of the 2nd Canadian Mountain Rifles to take up a commission as an officer in the Scots Greys. It is his death that sparked resentment and tension among soldiers who then found an outlet in the destruction of local businesses.[3]

The Riot

The riot began on Saturday May 8th, with rumours that the there was a celebration of the sinking of the Lusitania taking place at the Kaiserhof hotel downtown. Off-duty soldiers from Willow Camp arrived and at first stuck to singing “Rule, Britannia!” while hanging Union Jacks around the hotel.[4] The mob grew to several hundred mainly men and was accompanied by a crowd of one to two thousand spectators. As the mob increased it became more rowdy, furniture was destroyed and thrown out the windows, looting of businesses and bars began. The police arrived but before they could control the crowd, the mob moved on to the German Club before returning to the hotel. Further destruction and looting was done at Moses Lenz Wholesale Merchant, Messrs, Simon, Leiser & Company and various other shops downtown.[5]

![Damage to German Consulate [BC Archives: 193501-001]](https://onlineacademiccommunity.uvic.ca/vicpdgreatwar/wp-content/uploads/sites/1659/2015/11/f-02193_141.jpg)

The British Colonist reported that the police and a small detail of soldiers sent from Willows Camp were unable to stop the destruction or make arrests. The police even appealed to the fire chief, asking them to turn their hoses on the crowd in an attempt to drive them off. The request was refused as, “it was no part of the fire department’s duty to quell riots when police and military authorities were available.[6]” Requests for more military support were met late Saturday night as select soldiers from the 2nd C.M.R. and the 88th Battalion were stationed as guards as rumored targeted business across town. By 1:30am 150 soldiers and the entire police force were on guard, dispersing crowds and arresting twenty men.[7]

![Police Outside the Kaiserhof Hotel [BC Archives: 193501-001]](https://onlineacademiccommunity.uvic.ca/vicpdgreatwar/wp-content/uploads/sites/1659/2015/11/c-07553_141.jpg)

Rioting continued on Sunday, resulting in a meeting at the Kaiserhof hotel between the Police Commissionaires and Mayor Stewart to request “a picket of soldiers for the protection of property and the keeping of order.[8]” The military revoked the leave of all soldiers, and infantry from the 88th Battalion and 2nd C.M.R. was joined by men from the 48th battalion. In total, it took the entire police department, 275 men from the 2nd C.M.R. and 200 other infantry to protect businesses and disperse the crowd[9]. By Sunday night the riots had mostly dissolved and police began the process of laying charges and recovering stolen property.

The Aftermath

Police encouraged looters to return stolen property to police headquarters, they received enough parcels to dedicate an entire office to the storage and return of the goods[10]. Though the police initially arrested 20 men during the riots, they were let go after their names were taken. On Monday May 10, Reginald Vernon and F. Simmons were arrested for attempting to incite a riot, while Constable Owens arrested Richard Draft for unlawful assembly[11].

Several arrests were made and charges laid for the possession of stolen goods in the weeks following the riot. ‘Sam’ was arrested by Constable Elcter for stealing a sweater and sentenced to two months in prison. John Pastro and William Catsifas were charged for possession of stolen property and also sentenced to two months imprisonment. George E. Oconom, a waiter at the Kaiserhof Hotel, was arrested for stealing a bolt of cloth. Though he asserted his innocence at the Police Court, he was sentenced to one month in prison[12].

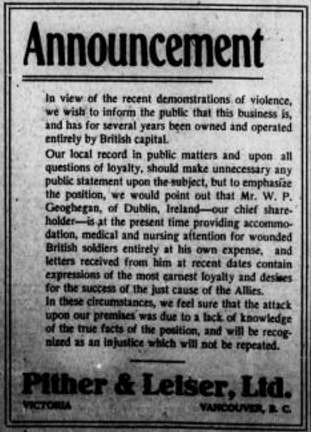

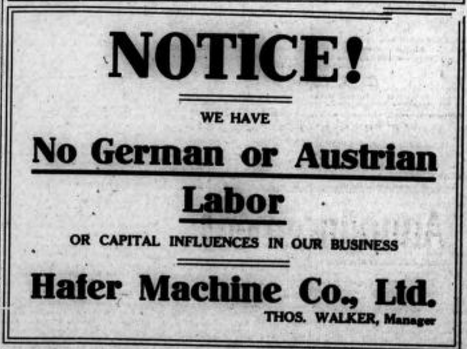

It was estimated that the rioters did $60-70,000 worth of damage to local businesses in the downtown area[13]. The riots were driven by anti-German feelings, however it resulted in mass damage to local Victorian business owners. Announcements by companies were soon placed in newspapers informing the public of their British roots, dependence on only British capital, and the support major stakeholders had given the war effort. The riots not only damaged Victoria’s economy, but also revealed anti-German feelings among Victorian residents and the struggle the police department faced in maintaining peace during this frustrating and devastating time.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0ikH8Vl3psA&feature=share

War Comes to Victoria (clip). BC Archives: AAAA1107

Written by Isobel Griffin

References

[1] “Submarine Gets over 1400 Victims.” British Colonist, May 8, 1915, front page.

[2] “Victorians Who Were Aboard.” British Colonist, May 8, 1915, front page.

[3] George R. Pearkes, interview by Ruth Chambers, October 21, 1975. BC Archives: T1787.

[4] Richards, Arthur T. “(Re-) Imagining Germanness: Victoria’s Germans and the 1915 Lusitania Riot.” MA Thesis, University of Victoria, 2012, 60.

[5] “Reads Riot Act to Quell Disturbances.” British Colonist, May 11, 1915, p.5.

[6] “Rioters Wreck City Premises.” British Colonist, May 9, 1915, p.2.

[7] Richards, “(Re-) Imagining Germanness,” 64.

[8] Ibid., 65.

[9] Ibid., 69.

[10] Ibid., 70.

[11] Ibid., 70.

[12] “Riots Aftermath in Police Court.” British Colonist, May 13, 2015, p.5.

[13] “Canadian Citizens Victims of Riots.” British Colonist, May 10, 2015, p.5.