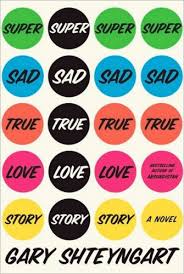

It’s Saturday night and you’re out on the town with a couple friends hoping to hit up the bar and get lucky. After working all week everyone has high spirits and can’t wait to get a jump on the nights activities. You’re all pumped up and ready to go until you arrive. Once inside, your äppärät kindly informs you that you are the third most unattractive guy in the bar with a horrible credit rating, bad personality score, and a 120/800 “fuckability” rating. Your night is ruined. The novel Super Sad True Love Story by Gary Shteyngart uses a device called an äppärät religiously. The entire world of the novel revolves around these devices. They hold everyone’s data and can be used in a number of different formats; it’s like the iPhone, but worse. In brief: the äppärät is an NSA agent’s wet dream. The use of äppäräts in this novel shows how technology has made us vulnerable and it demonstrates how such an advancement could lead to humans losing control over who we are.

The story takes place in New York in a time where the government of the United States is severely indebted to Chinese creditors. It’s written in a style that flips between online instant messaging and the diary of a couple living during this time via their äppäräts. The two main characters are Lenny, a 39 year old Russian who prefers to live in the past, and Eunice, a young Korean girl raised by an abusive father who is full of personal issues. The narrative begins with the two meeting in Rome and Lenny falling instantly in love with Eunice. He asks her to move in with him in Manhattan and, although Eunice hardly thinks anything of Lenny, she agrees due to family issues back home in Fort Lee. Eunice slowly develops feelings for Lenny and both are happy for a time in their mixed up world. This changes when Eunice is introduced to Lenny’s more outgoing and attractive boss, Joshie, and begins to fall for him instead. Joshie, who is the owner of a life extension nano tech company, had nanotechnology inputted into his body to preserve his life. This is what allows him, a 70 year old, to appear younger than Lenny. Eunice has an affair with Joshie, and when she comes clean Lenny leaves the crumbling ruins of the USA for Canada, changing his name to Larry Abraham. The reader then finds out that someone has hacked into Eunice and Lenny’s private accounts and that the entire story has been published without their consent.Throughout all of the events and changes that take place in this book there is one consistent trait: everyone is always on their äppärät.

In the novel a äppärät functions like an iPhone on a necklace. It has all the features of a modern day phone or tablet but it can project information to other people’s devices as well. People use these devices to communicate with each other as well as rate and judge other people. The 7.5 model of the äppärät has a built in “rate me” ability; it takes all of your personal information as well as the person you are interested in and through an algorithm gives a rating based on everything from credit, to personality, to even “fuckability” (which I find very odd). All one has to do is point their äppärät at someone and it allows them access to personal information such as age, net worth, political position, and even personal photos. People become too attached to it; some even commit suicide when the äppäräts are down and left notes saying that “they couldn’t see the future without their äppärät.” After large explosions hit the city, many are more worried about their äppärät than each other. Without being connected, everyone starts to break down.

I believe there is such a thing as being “too connected” with technology. I am extremely uncomfortable with the idea of a stranger being able to point their device at me and view most of my information with a simple tap. Not only that but it was deemed abnormal and suspicious not to have a äppärät in this world. I would say, “imagine if we lived in a world where society would judge you for not having a phone or something like an äppärät,” but we do. If unarmed without a device such as an iPhone, Black Berry or smart phone of any type, people will judge and question your actions. I do know about 2-3 people who do not own a cell phone by choice (not for financial reasons) and applaud them for it, but at the same time I can’t help but wonder why and I know I’m not the only one. Many will say that they are not one to judge if someone isn’t up to date and connected in the cyber world. But sadly deep down, we all do.