Environmental psychologists note that despite world recognition of the impact of greenhouse gas emissions and climate change, a significant percentage of the global population are reluctant and resistant to change (De Boer et al., 2013; Rosenfeld & Tomiyama, 2022).

For the past ten years, environmental psychologists (De Boer et al., 2013; Rosenfeld & Tomiyama, 2022) have noted that disbelief about dietary changes mitigating climate change pose challenges for environmentally-relevant consumer behaviour.

“Skepticism is noted as developing through traditional beliefs about the climate and difficulties with understanding the basic notion of human induced climate change”

De Boer et al., 2013

Dr. Robert Gifford, professor of psychology at University of Victoria, notes structural and psychological obstacles exist that hinder behavioral efforts and suggests dragons of inaction are psychological barriers that limit climate change mitigation and adaptation.

Seven categories of psychological barriers, or “dragons of inaction”:

- limited cognition about the problem

- ideological worldviews that tend to preclude pro-environmental attitudes and behavior

- comparisons with key other people

- sunk costs and behavioral momentum

- discredence toward experts and authorities

- perceived risks of change

- positive but inadequate behavior change

A Brunswik lens model is a concept of probabilistic functionalism design that is utilized in environmental psychology as a theory of perception, originated by Egon Brunswik. This perception will help with decision making and eventually guide outputs for sustainable products and recipes. The model design considers various input cues to determine an overall rating for sustainable food products in Canada and food products promoted or used on campus.

| Brunswik Lens Model perception cue | Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) | SDG Images | Sustainable Development Goals (UN) |

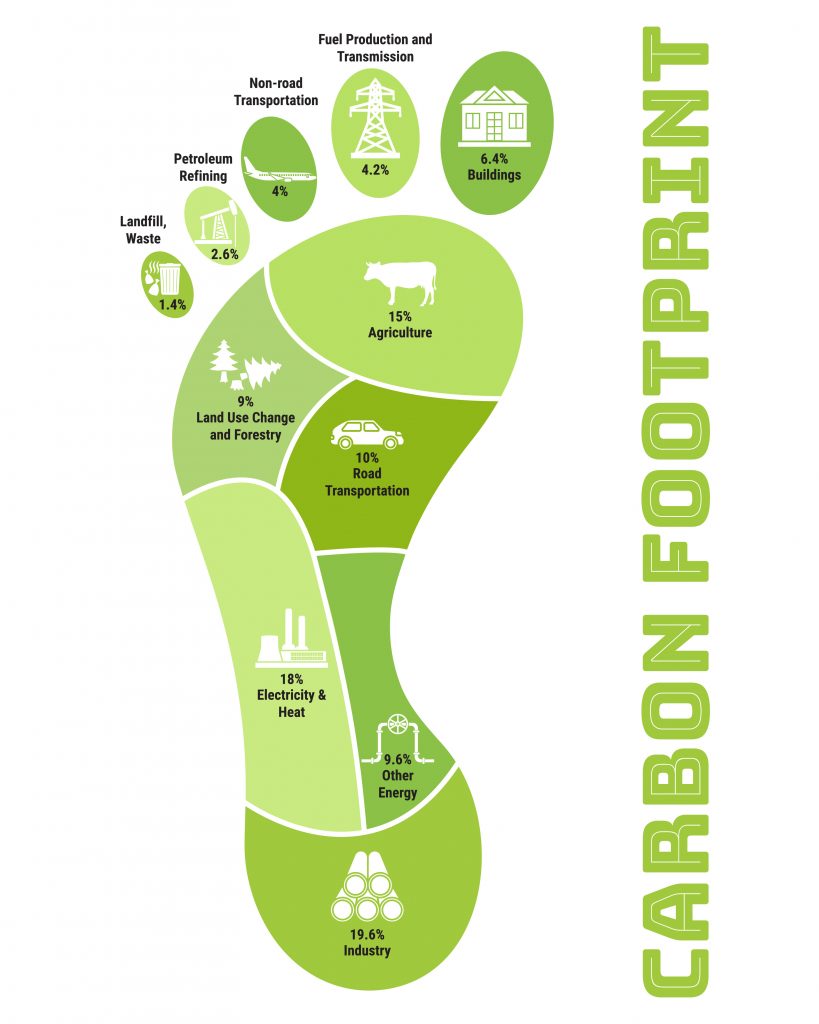

| a) emissions caused directly by raising animals and livestock (global antropogenic, enteric fermentation and manure); | According to FAO (2015) emissions reduction from the livestock sector can be achieved by reducing production and consumption. |  | Goal 12- Ensure sustainable consumption and production patterns. |

| b) production location (cost of transport for distribution) | The production of vegetables is one response to the changing diets and challenges enforced on the food supply that rapid urbanization has caused |  | Goal 2- End hunger, achieve food security and improved nutrition and promote sustainable agriculture |

| c) technologies required to use food product/recipe (oven, water, refrigerator) | assumptions may be made about the technologies available, human and natural resources. Increase motivation through developing local commitment including a better understanding of individual priorities |  | Goal 7- Ensure access to affordable, reliable, sustainable and modern energy for all |

| d) packaging (is it biodegradable, can it be recycled, reused, edible) | risk factors or sources of pathogens, limited access to piped water, and a lack of cool transport and storage |  | Goal 13- Take urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts. |

| e) waste (ability to change serving size, percentage of food product used | concerns related to: polluted irrigation systems such as the use of wastewater, wastewater treatments. natural ecosystems are degrading due to the unsustainable manner in which resources are being used |  | Goal 6-Ensure availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all. |

| f) capacity (qualified agricultural expertise, innovative engineering) | The FAO currently hosts a global community of practice that facilitates dialogue, information exchange and sharing of ideas related to the use of information and communication technologies. https://www.fao.org |  | Goal 4- Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong opportunities for all. |

| g) institutional priorities and constraints (square footage, risk, liability, cost, ownership, business contracts, partnerships) | Suggestions to increase motivation through developing local commitment included a better understanding of individual priorities and how those align with institutional priorities constraints and capacities |  | Goal 9- Build resilient infrastructure, promote inclusive and sustainable industrialization and foster innovation. |

| h) import/export (is it a cash crop for Canadian farmers, or a backyard business) | Institutional determinants that affect smallholder farmers include gender relations, markets, standards, income distribution, land titling and systems of governance |  | Goal 1- End Poverty in all forms everywhere |

A parent’s decision to make dietary changes for climate action may help their child to adapt at a faster and easier rate through modelling and experience. This belief is supported by Darwin’s (1869) Origin of the Species “survival of the fittest” which postulates, the ability to adapt to your environment is the key to reproductive success.

In terms of dietary change, a child that has never eaten specific food products, may never miss their disappearance in the future nor struggle with challenges related to behaviour and dietary change inflicted when a familiar or comforting food product is not available or limited in availability and some may experience cravings or a sense of loss connected to their childhood and memories of family meals. Often the generational passing down of family recipes is a cherished keepsake. Similarly, a child that learns to grow and eat sustainable foods may not struggle with challenges related to 2030 Net Zero goals. Ideally, a child that was surrounded by wisdom provides innovation to others.

Adults in their 40s may never experience the impact of 2050, but the survival and success of their younger successors may depend on the choice to. Business opportunities in the future depend on their expertise related to these problems and innovative solutions. In all likelihood, grant monies from government bodies will require a specific benefit to UN Sustainability Development Goals.

The purpose of this sustainable project is to develop a system of rating food products (i.e. food index) based on sustainability practices that can be modelled for University of Victoria students and staff.

The objective to promote sustainable food products and recipes submitted by community members is based on a published and measurable goals for University of Victoria to achieve net zero through the reduction of GHGE.

References

De Boer, J., Schösler, H., & Boersema, J. J. (2013). Climate change and meat eating: An inconvenient couple?. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 33, 1-8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2012.09.001

Gifford, R. (2011). The dragons of inaction: psychological barriers that limit climate change mitigation and adaptation. American psychologist, 66(4), 290. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0023566

Gifford, R., Lacroix, K., & Chen, A. (2018). Understanding responses to climate change: Psychological barriers to mitigation and a new theory of behavioural choice (p. 161-184). In Clayton, S. & Manning, C. (Eds.). Psychology and climate change: Human perceptions, impacts, and responses. New York: Academic. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-813130-5.00006-0

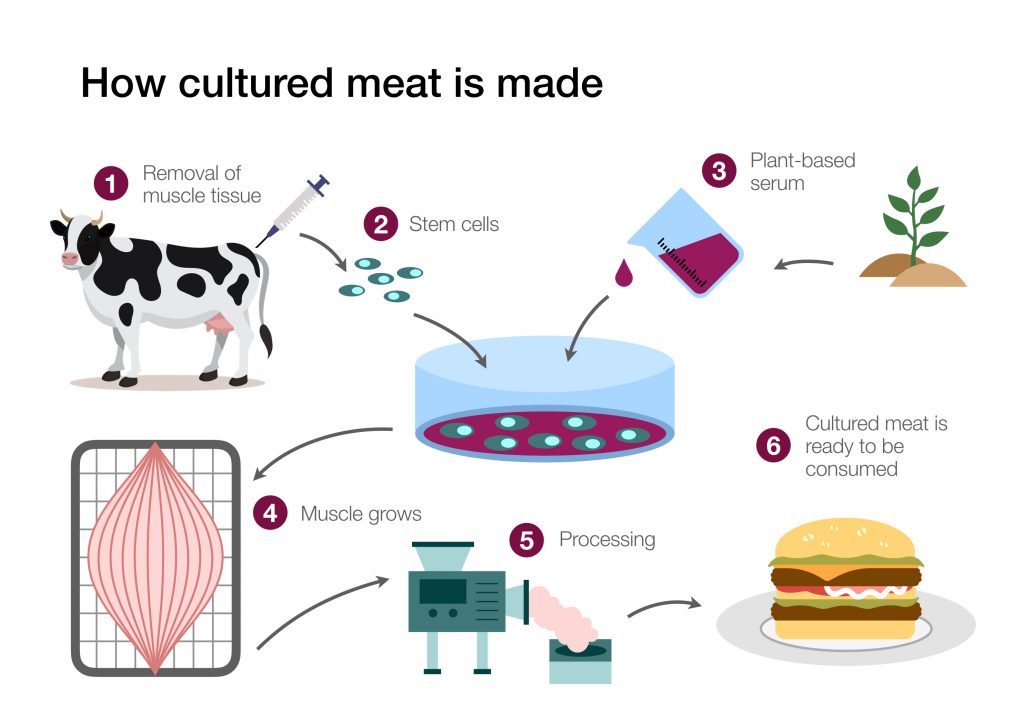

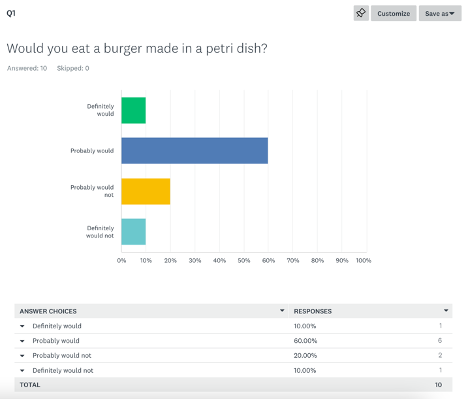

Rosenfeld, D. L., & Tomiyama, A. J. (2022). Would you eat a burger made in a petri dish? Why people feel disgusted by cultured meat. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 80, 101758.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2022.101758