Realistically there was little society could do to stem the spread of this virulent disease. The age-old technique of isolation in quarantine was proposed but keeping people in isolation meant clamping down on public gatherings, whether this was at a school, business, church, or places of amusement, and it met with opposition. In Vancouver the Medical Officer of health, Frederick T. Underhill, did not believe that closing schools, theatres, etc. would be effective, but neighbouring towns disagreed, believing that Vancouver would become a reservoir for the disease. Victoria even asked to be quarantined from the mainland.[1] Across North America the consensus among health professionals was that quarantine was “not worth the effort”.[2]

PETER — ARE YOU ADDRESSING THE MATTER OF CLOSURES ETC.?

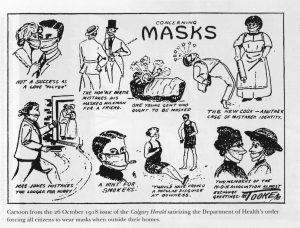

The wearing of masks was similarly rejected, at least in British Columbia, although it was required in Alberta. [3] In theory the mask would prevent a sick person from passing on the disease, and the healthy from contracting it. But this only worked if the mask was kept scrupulously clean, which people in general failed to do — a contaminated mask was as dangerous as no mask; but this seems to have little effect as most people only pulled them into position when the police appeared.[4]

Recognizing that there was little they could do to protect themselves from the ‘flu, the general populace turned to alcohol and patent medicines, most of which contained some narcotic. A range of products — from laxatives to sleeping powders — were advertised as being beneficial against the ‘flu. In truth, no drug “could prevent or cure influenza”. And there was no possibility of a vaccine. Apart from the fact that the disease was spreading so quickly and there was no time for research, it was not until 1933 that there was a microscopes powerful enough to identify the organism, which until that time had been thought to be a bacterium. [5]

The most effective procedure was nursing care, keeping the patient “hydrated, rested, and warm”. In Victoria, the Sisters of St. Ann were amongst those who provided this care; it was not without its risks – Sister Mary Joseph and Sister Mary Alodie succumbed and died.[6]

1. Mark Osborne Humphries, The Last Plague: Spanish Influenza and the Politics of Public Health in Canada (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2013), p. 112, n. 19.

2. Janice P. Dickin McGinnis, “The Impact of Epidemic Influenza: Canada, 1918-1919”, Historical Papers / Communications historiques, Volume 12, Number 1, 1977, Pages 20-140, p. 126. <http://id.erudit.org/iderudit/030824ar> accessed on 3 March 2014.

3. Emily Yearwood-Lee, “Flu Pandemics of The 20th Century The B.C. Experience”, Background Brief 2009: 01 / September 2009, Legislative Library of British Columbia, p. 4. <http://www.llbc.leg.bc.ca/public/pubdocs/bcdocs/460566/200901bb_flu.pdf> accessed 1 March 2014.

4. McGinnis, “The Impact …”, p. 126. <http://id.erudit.org/iderudit/030824ar> accessed on 3 March 2014.

5. McGinnis, “The Impact …”, p. 127. <http://id.erudit.org/iderudit/030824ar> accessed on 3 March 2014.

6. Darlene Southwell, Caring and compassion : a history of the Sisters of St. Ann in health care in British Columbia (Madeira Park, BC : Harbour Publishing, 2011), pp. 62–63.