On October 1, 1918 Victoria resident Mable [sic] Mary Brown died of Septic pneumonia. From Dublin, Ireland, she was just 20. She fit the profile of the Spanish flu’s primary victims — young and healthy.

Mable Mary Brown’s death registration, accessible via BC Archives’ genealogy search engine.

The same day, Victoria Medical Health Officer (M.H.O.) Dr. Price reassured Colonist readers that the rumours of an outbreak were untrue: “So far there were no cases here.” But if there were, public health and “duty to the Empire” would justify “the closing of all schools, moving picture houses and public meeting places.”

“Prepare to Keep Epidemic Away,” Colonist, October 2, 1918, p. 2.

Meanwhile Victorians were breaking attendance records at the Home Products Fair.

“Crowds Smash Record Again,” Colonist, October 3, 1918, p. 1

The news from the Eastern United States just got worse … Cases in army camps since the epidemic began September 13 totaled 113,737; a staggering 2,479 deaths. In Boston 191 people died on October 2.

“Influenza finds Host of Victims,” Colonist, October 4, 1918, p. 11

There was fresh cause for immediate concern as soldiers with the 259th and 260th Battalions began arriving at the Willows Camp on October 2.

Benjamin Isitt, From Victoria to Vladivostok, UBC Press 2010, pp. 83-4, 214 fn 69.

By October 4 the Victoria M.H.O. was reporting “a number of cases in Victoria” — but none in Vancouver.

“Guard Against Epidemic,” Colonist, October 5, 1918, p 6.

On Saturday, October 5 Victoria mayor Albert E. Todd published an appeal on page 1 in the Colonist urging the public to turn out to the “Made-in-Victoria” Fair in record numbers and predicting that “Victoria, ‘The Fighting Port,’ will rise to the occasion.”

“Mayor to Public,” Colonist, October 5, 1918, p. 1.

The same tension as between the M.H.O.’s warning and the mayor’s invitation will be evident throughout the eighteen months the Spanish flu was present or threatening.

On Sunday, crowds of visitors mingled at the Saanichton Fair.

“Fair at Saanichton Draws Many Visitors,” Colonist, October 6, 1918, p. 4.

On Monday, October 7 the 27-year-old manager of the Pantages Theatre on Government Street died in hospital.

“Theatre Manager Dies after Short Illness. Mr. Frank Stanfield Succumbs to Pneumonia at St. Joseph’s Hospital Monday Morning,” Colonist, October 8, 1918, p. 7.

That day, amid reports of “50 to 100 cases” of Spanish flu, the Victoria and Saanich M.H.O.s huddled with their political masters.

On Tuesday, October 8, all schools in Victoria, Saanich and Oak Bay closed, as well as all indoor meeting places in the city. The Provincial Health Officer obtained an order-in-council from the B.C. cabinet to buttress the local authorities’ powers.

“City Will Act to Check Epidemic. All Churches, Theatres, Schools and Meeting Places to Be Affected by Closing Order—Saanich Already in Line.” Colonist, October 8, 1918, p. 4.

The city-wide ban on meetings would remain in force until November 20.

Victoria M.H.O. Annual Report 1918, p. 89.

To it was added the M.H.O.’s advice to forego open-air church services and the like.

“Open Air Meetings,” editorial, Colonist, October 13, 1918, p. 4

The city’s initial responses were outlined in the year-end Medical Health Officer’s Annual Report [paragraphing added]:

A ban was placed on all indoor assemblies[;] churches, theatres and schools were closed from October 8th to November 20th.

Directions as to how to avoid infection and how to act if infected were published in the daily papers, warning notices were distributed and addresses given to working men.

Houses where influenza occurred were placarded and the patients quarantined until free from infection.

An Emergency Hospital was opened and the City Isolation Hospital prepared to receive influenza cases.

There being an inadequate number of graduate nurses to cope with the number of cases in the City, amateur nurses were organized and many lives were saved through home nursing by volunteer ladies.

At Willows, the Siberian battalions were just settling in when a serious outbreak of influenza swept through the camp. A quarantine barracks was set aside and soon filled to overflowing with flu cases. Stadacona Park, with an empty house owned by the city, less than a mile from Willows Camp, was converted to an isolation hospital for soldiers.

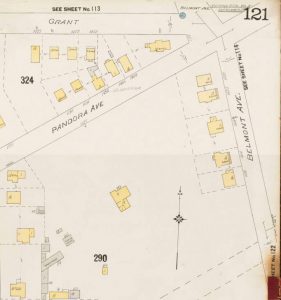

Stadacona Park Military Hospital’s isolated situation can be gleaned from the 1913 fire insurance map:

Note the roadway labelled Pandora Avenue; it was later renamed Begbie Street, and Pandora extended east to Fort Street near where the dotted lines appear.

Even after those strong measures, eight military deaths followed in the week October 14-20.

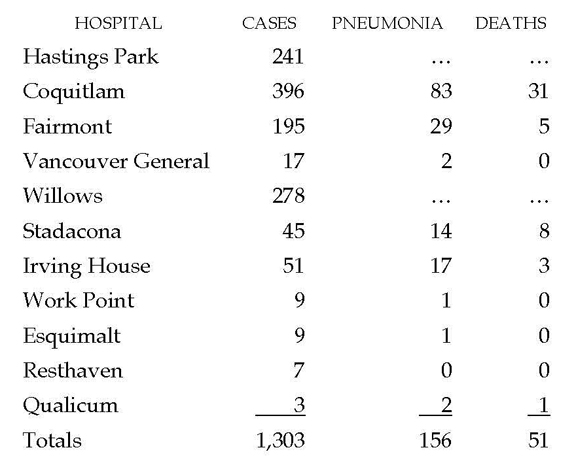

The army medical officer’s end-of-month report provides a measure of the success of enforced quarantine and isolation. Lt.-Col. C. E. Doherty was Assistant Director of Medical Services (A.D.M.S.) for Military District 11, which took in Vancouver, the Lower Mainland and Vancouver Island. His report to Ottawa at the end of October 1918 showed the number of cases of influenza and lethal pneumonia and the number of deaths at all military hospitals for the month:

As published in The Daily Colonist, November 17, 1918, p. 4. In the table, the third column, Cases of Pneumonia, is part of the second, Total Cases of Influenza, not additional to it.

In brief, military personnel died of influenza at the rate of almost four in one hundred cases (51 is 3.94 per cent. of 1,303) in October. A stringent plan was put in place — “temperature parades” twice a day, instant segregation of the infected, regular sanitary inspections of hospitals. The result was a “marked decline in number of new cases, until now it is possible to say the disease is all but non-existent among soldiers in this Military District.”

“A Notable Feat,” editorial, Colonist, November 17, 1918, p. 4.

In the city the epidemic raged for more than a month. Among the early casualties were caregivers; see the Memorial section.

In the City of Victoria’s temporary emergency hospital, beds were soon going empty not for lack of patients but for want of nurses and nurses’ assistants. M.H.O. Dr. Price issued frequent and increasingly urgent appeals for more volunteers to step forward and train in basic caregiving. It was represented as a duty. During several critical periods of multiplying cases, the response was never enough.

In Saanich, still largely rural, with dirt roads winding through old-growth forest, the home-visiting Victorian Order of Nurses were front-line caregivers in the battle with the flu. Saanich Police Chief James Dryden was part of the emergency team. He made a report to Saanich council on November 5, 1918. The archives have preserved his hand-written text, and the Colonist’s extensive coverage distilled Chief Dryden’s description of the challenges the Spanish Flu posed in Saanich:

… Chief of Police Dryden … presented a report of the present outlook for control of the plague and the number of known cases … in Saanich. He reported … at present 196 known cases in the municipality, of these seven are serious. … at least two deaths, Mrs. Swallow, of Falmouth Road, and Mr. Persetti, of Wilkinson Road, having succumbed within the past week. … the average number of cases seen each day for several days past has been between fifty and sixty … the work done by the Victorian Order Nurses Forshaw and Headington was one of the main reasons why the epidemic had been kept within controllable limits.

The work had been too much for those in charge of the campaign, and at the time Chief Dryden made his report to the Council Nurse Forshaw had been stricken with the disease and Medical Health Officer Dr. J. P. Vye was also a victim.

… The majority of cases were in Wards 2 and 7 … many other unreported cases … new cases averaging from seven to ten each day, and if it were possible to get all the patients to report to the medical officer the number of known cases would take sudden jump.

Chief Dryden expressed the conviction that the best procedure would have been for Saanich to have established an isolation hospital in the earlier days of the epidemic in order that the spread of the disease through families might have been stayed. Experience showed, he said, that the illness in nearly every case went completely through a household when the first person to get it was not isolated. … In the past week the police automobile had travelled 1,100 miles in connection with influenza cases, and the car operated by the Victorian Order of Nurses had done even more. …

Since his report to the Council on Tuesday, Chief Dryden has been taken ill with what is believed to be the influenza, and the Victorian Order reports an addition of ten cases to the list of known cases yesterday, with an unconfirmed report of an additional death. …

Colonist, November 7, 1918, p. 8.

The president of the Saanich branch of the V.O.N, Maude Hall, in her second (1918) annual report, captured the stress the nurses worked with:

But it was in November that the Victorian Order Society proved its worth, 591 visits being paid by the nurses [2] in that one month. Whole families were stricken down by the plague and our nurses were working almost day and night. Before long, Nurse Forshaw, who had become our first nurse, collapsed through strain and overwork and contracted the Influenza. Miss Headington, who had left us in September to take up War Work, showed her splendid humanity by at once offering to return and take up the work Miss Forshaw was prevented from doing. The Board accepted the work of Miss Headington with great thankfulness. Miss Norcross of Victoria also helped during this trying time, and our gratitude goes out to her and to our sister Society. Several other helpers were engaged and their services were paid for by the Council. The girl Guides showed that they were indeed “Daughters of the Empire” for they helped with the fight againt disease by making Pneumonia jackets.

Saanich Clerk’s Office Correspondence 1906-1946. Box 13, files 2-3 (1919). Saanich Archives.

Nurse Jessie Forshaw submitted reports of each month’s activities of the Victorian Order of Nurses in Saanich. On the same form she compiled a report of the year’s activities for 1918. In the annual report she noted she had been off duty from November 3-20 with influenza, and again from November 25 to December 3.

During the second absence, Forshaw returned to her family home in Vancouver, where on November 26 her 18-year-old brother Jabez died of influenza.

A longer view of the epidemic in the Town of Esquimalt can be surmised from the 1919 annual report to Council of the Medical Health Officer, Dr. Edward Boak. (He did not submit a report for 1918.)

During the winter of 1919, with the pandemic of influenza raging, Esquimalt suffered severely, but not out of proportion to other Municipalities. The schools were closed during the height of the epidemic, and all public meetings banned. When the diseases subsided and the schools reopened, all children with colds or in whose houses illness prevailed , were kept away from school as a precaution. Notices were posted inconspicuous places warning the public of the danger of crowds, and all possible efforts were made to prevent the disease spreading.

T. W. Boak, MD. letter to the Reeve and Council, January 1, 1920, in The Corporation of the Township of Esquimalt, Financial Statements and Reports as at December 31, 1919. Township of Esquimalt, Annual Statements 1912-1945. At Esquimalt Archives.

As for Oak Bay, most of the municipal records were destroyed in a flood in the late 1940s. A review of the surviving Minutes Books could yield information on its response to the epidemic.