Two notable characteristics of the Spanish ‘flu were an “extremely by high mortality”, and a condition known as heliotrope cyanosis.[1]

Cyanosis is a blue discolouration of the skin, it occurs when the oxygen supply is reduced resulting in the diversion of blood to the major body organs and away from the skin.[2]

A physician at Camp Devens near Boston Mass. noted that this “epidemic started about four weeks ago, and has developed so rapidly that the camp is demoralized and all ordinary work is held up till it has passed….These men start with what appears to be an ordinary attack of La Grippe or Influenza, and when brought to the Hosp. they very rapidly develop the most viscous type of Pneumonia that has ever been seen. Two hours after admission they have the Mahogany spots over the cheek bones, and a few hours later you can begin to see the Cyanosis extending from their ears and spreading all over the face, until it is hard to distinguish the coloured men from the white”.[3]

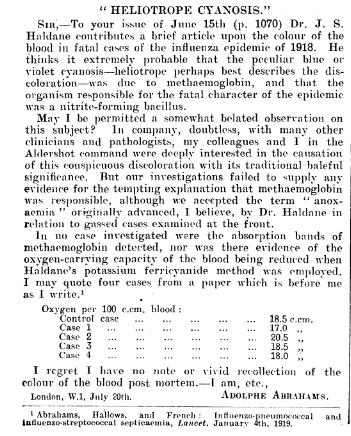

The name Heliotrope cyanosis was not in use during the epidemic, but was suggested as an apt description of the colour by Adolphe Abrahams, in a letter to The British Medical Journal in July 1929.[4] ↩

1. J. S. Oxford, “The So-Called Great Spanish Influenza Pandemic of 1918 May Have Originated in France in 1916”, Philosophical Transactions: Biological Sciences, Vol. 356, No. 1416, The Origin and Control of Pandemic Influenza (Dec. 29, 2001), pp. 1857-1859, p. 1857. <http://www.jstor.org/stable/3067060> accessed on 14 March 2014.

2. <http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/ency/article/003215.htm> accessed on 27 March 2014.

3. <http://www.flu.gov/pandemic/history/1918/your_state/northeast/massachusetts> accessed on 27 March 2014.

4. Adolphe Abrahams to the editor, The British Medical Journal, 27 July 1929, p. 166.

<http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/ency/articles/PMC2451452/?page=1> accessed on 27 March 2014.