Backward Design and Understanding by Design

I’ve come to realize that having a clear goal before taking action is one of the most important parts of learning. This module reminded me of how often I apply this without even thinking about it. In everyday life, I rarely jump into something without knowing what outcome I want, and the same is true for my studies.

One clear example comes from my university math classes. At first, I used to just sit in lectures and listen to the teacher. The problem was, I couldn’t tell what I was really supposed to learn. The textbook made things even worse—it was expensive, very detailed, and I had no idea which parts were essential. If I tried to study every single word, it would take forever and leave me with a lot of information that I would never actually use. It felt like walking through a forest without a map.

Things only started to make sense once homework assignments or practice exams were given. Suddenly, I knew exactly which chapters and concepts were important, and I could focus my energy there. Instead of wasting time on “useless” details, I could study with a purpose. Even though it might sound utilitarian—basically studying for tests—it was effective. It saved time, gave me a sense of direction, and made me feel that my efforts were actually leading somewhere.

Design Thinking

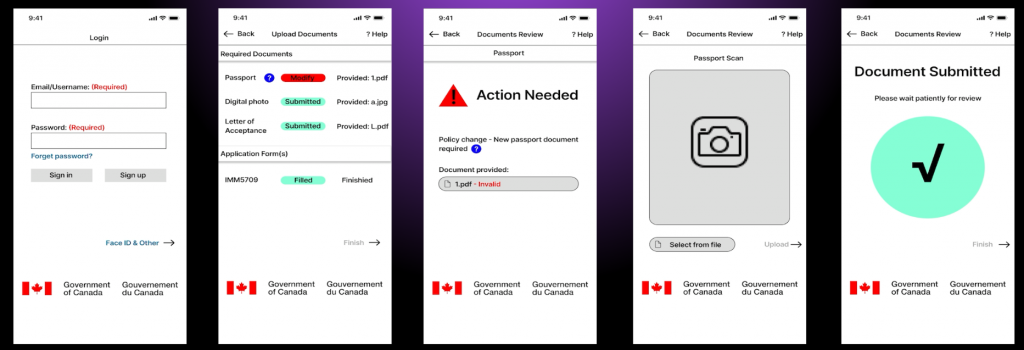

This is an area I feel quite familiar with, because last semester I took a course on Human-Computer Interaction where we focused a lot on designing with the user in mind. The most important step is to think from the user’s perspective. Designers and users often think in very different ways, and once you already know how something works, it’s easy to forget how confusing it might be for a beginner. That’s why testing is so important. In that class, my group designed a Canadian visa application app. Through testing with classmates, we found many issues we didn’t notice at first, such as confusing page layouts and counterintuitive navigation. Their feedback helped us improve the design and make it more user-friendly.

Learning Outcomes and Bloom’s/ SOLO Taxonomies

This depends on the specific situation. There is no absolute better or worse. For a science major like me, Bloom’s Taxonomy is more helpful because most of the time I need actionable and measurable goals, not vague “understanding”. At least in mathematics or science, there is no vague understanding, only 0 or 1. For example, a weak outcome might be “students will understand fractions.” A stronger outcome would be “students will be able to apply fraction rules to solve real-world problems, like dividing a recipe in half.” The second one is clearer and measurable, which makes learning more meaningful.

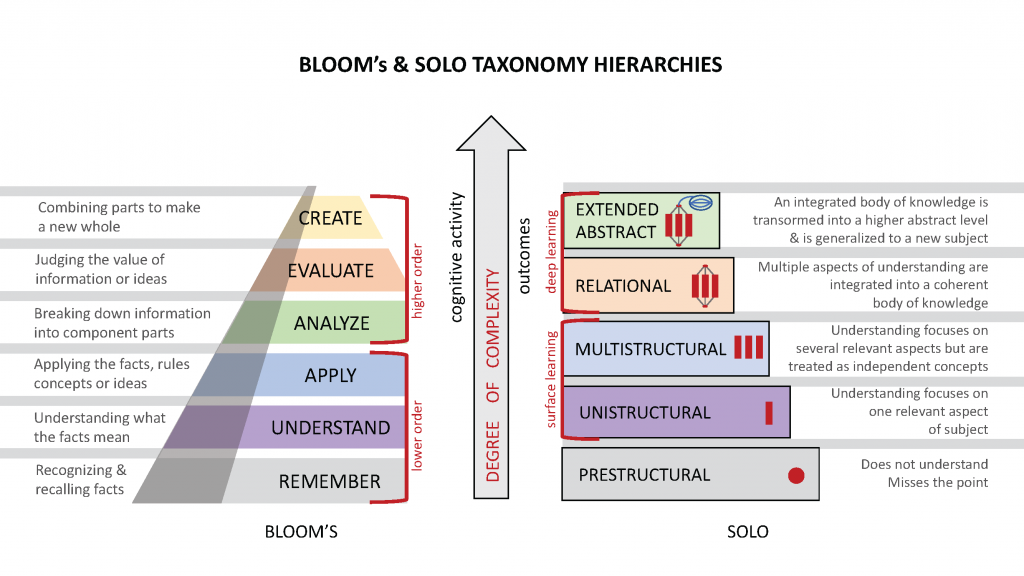

This diagram compares Bloom’s Taxonomy and the SOLO Taxonomy. Bloom’s is usually shown as a pyramid, moving from remembering and understanding at the bottom to applying, analyzing, evaluating, and creating at the top. Each level represents a type of thinking, with the higher levels requiring more complex work (Anderson & Krathwohl, 2001).

SOLO looks more like a staircase. It shows how deep a learner’s response is, from no clear understanding, to listing a few points, to linking ideas together, and finally applying knowledge in new contexts (Biggs & Collis, 1982).

Used together, Bloom’s helps us write clear objectives, while SOLO helps us see how well students really understand.

Better Learning Design

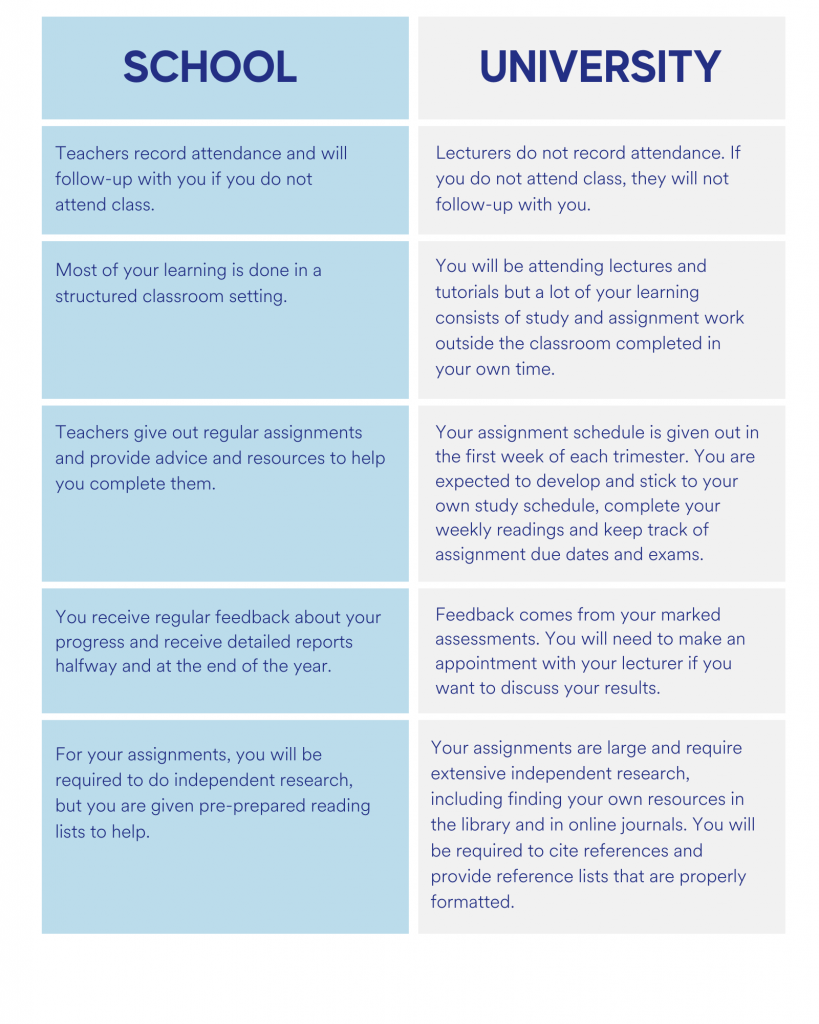

When I look back, most of my learning before university was surface learning. In junior high and even in high school, just memorizing things was often enough to get a decent score, even in harder classes like AP. I didn’t really go that deep, and honestly part of it was because my English wasn’t great, so I didn’t spend extra time trying to fully understand.

University was different. In my coding courses, memorizing never helped. The exams didn’t just test whether I remembered the grammar of a language; they asked me to solve problems and show how the logic worked. That kind of design made me realize surface learning wasn’t going to work anymore. If I wanted to pass, I had to actually understand the concepts and practice applying them.

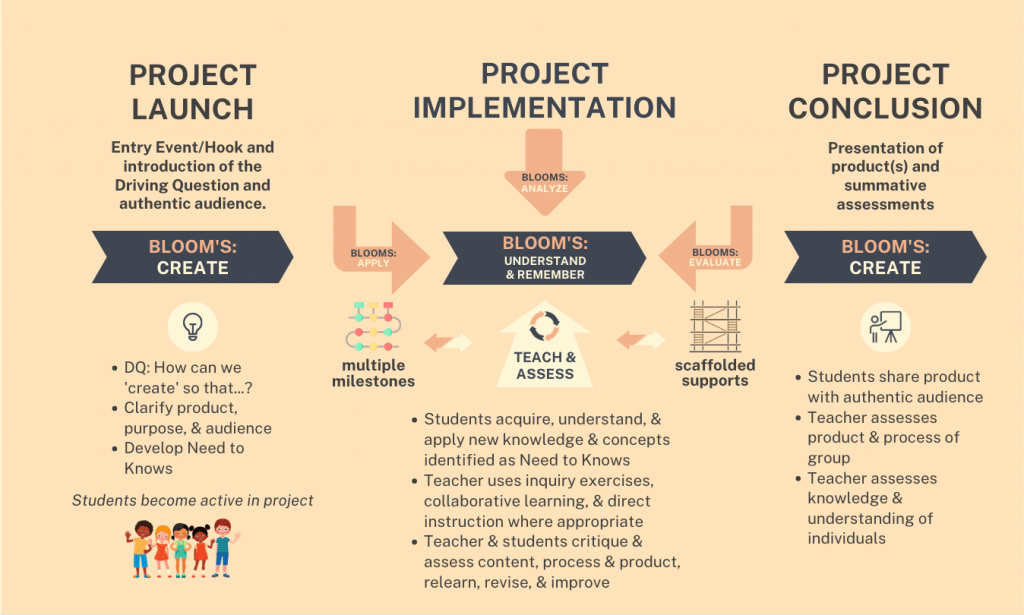

Inquiry and Project-Based Learning

For me, project-based learning connects really well with how I study computer science. In coding classes, I usually don’t get the idea just by reading or listening. It only starts to make sense when I actually build something, like a small app or a project with my classmates. Inquiry-based learning feels similar to research. You start with a question, and you don’t know the answer yet, so you explore different ways until you find something that works.

The good thing is that it feels real. Working on projects gives me motivation and shows me how the knowledge can be used outside of exams. It also teaches me how to work with others. The hard part is that open-ended tasks can be confusing—you don’t always know where to start, and it takes more time. But in the end, the learning sticks much better.

References

Anderson, L. W., & Krathwohl, D. R. (2001). A Taxonomy for Learning, Teaching, and Assessing. Longman.

Biggs, J., & Collis, K. (1982). Evaluating the Quality of Learning: The SOLO Taxonomy. Academic Press.