by Heather Croft | Feb 11, 2026

- Research the Company

Make sure to familiarize yourself with the company’s mission, values, and any recent news or projects. Understanding the organization will help you speak confidently about why you’re interested in the role and how you can contribute to their goals.

- Understand the Role

Review the job description carefully. Be sure you understand the key responsibilities and required skills. Think about how your past experiences-whether from school, volunteer work, or part-time jobs-can demonstrate your ability to excel in this role.

- Prepare STAR Stories

The STAR method (Situation, Task, Action, Result/Reflection/Relevance) is a helpful framework for answering behavioural questions. I suggest you prepare 2-3 specific examples that highlight your skills in areas like problem-solving, teamwork, and communication. These stories will help you respond effectively to questions that ask for real-life examples.

- Be Ready to Show Enthusiasm

Co-op positions are all about learning and gaining experience. It’s okay if you’re still building some skills, but be sure to emphasize your passion for learning, contributing to the team, and taking on new challenges.

- Ask Insightful Questions

Prepare a couple of thoughtful questions for the interviewer. Ask about the team culture, what success looks like in the role, or opportunities for growth. Asking these types of questions shows you’re genuinely interested in the position and the company.

- Dress Appropriately

Even if it’s a virtual interview, remember to dress professionally. First impressions matter, and dressing appropriately will help you feel confident and make a positive impression.

- Stay Calm and Confident

It’s normal to feel nervous, but if you do, remember that it’s okay to take a moment to collect your thoughts before answering. It’s better to provide a clear, thoughtful response than to rush through your answers.

- Follow-up

After the interview, send a short thank-you email. Express your gratitude for the opportunity and re-emphasize your enthusiasm for the position. This small gesture goes a long way in leaving a positive impression.

- Use AI for Practice Questions

Upload the job description to an AI tool and ask it to generate the top ten likely interview questions for this position. While the exact questions might not be asked, preparing answers to those questions will help you feel more ready and confident during the interview.

- Be Yourself

It’s important to stay true to who you are during the interview. Trying to be someone else might make you uncomfortable, and it’s likely to show. Employers value authenticity, so embrace your unique qualities and show how they’ll contribute to the role and company.

by Heather Croft | Dec 4, 2025

If you’re a data science co-op student, BC’s AI and quantum computing ecosystem offers an opportunity to apply analytical skills to real-world problems. Whether you’re passionate about machine learning, big data, or quantum algorithms, this sector is where your skills can directly shape the future of health, security, and global competitiveness. With a 10-year target to double tech-sector employment to 400,000 jobs and grow economic value by 75%, this is a space where data scientists will be at the heart of innovation.

Why Data Science Matters Here

- 600+ AI companies in BC, most already generating revenue, rely on data scientists to build, train, and evaluate models.

- Quantum computing research creates new frontiers for data analysis, optimization, and cybersecurity.

- The sector’s growth means more demand for data-driven insights across industries like health care, agriculture, geospatial analytics, and defence.

Current Opportunities

Data science co-op students can expect to work on:

- AI in medicine: algorithms for cancer screening and drug discovery

- Geospatial analytics: satellite imagery processed with advanced AI to detect real-time environmental changes

- Cybersecurity: quantum-ready solutions that protect sensitive data

- Applied machine learning: predictive modelling for agriculture, legal services, and public health

Goals That Shape Your Career Path

BC’s strategy includes:

- Leading Canada in developing and testing AI and quantum use cases

- Expanding AI adoption in businesses, creating demand for data scientists who can translate insights into ROI

- Establishing a K-12 AI advisory committee, signaling long-term investment in data literacy and workforce development

- Doubling the size of the AI and quantum sectors, meaning more jobs for analysts, engineers, and researchers

Why It Matters for Data Science Students

For co-op and early-career data scientists, this growth means:

- Hands-on experience with large-scale datasets in health, agriculture, and defence

- Opportunities to design machine learning pipelines and optimize algorithms for real-world impact

- Exposure to quantum computing applications, where data science meets next-generation hardware

- A chance to contribute to projects with global reach, from drug discovery to climate resilience

The Bigger Picture

- 75% of AI companies in BC are already generating revenue, showing strong market traction.

- The AI sector is projected to grow at a 24.3% annual rate, reaching $2.64 billion GDP by 2031.

- Investments in the Quantum Algorithms Institute (QAI) and partnerships with universities and industry ensure data scientists will be central to advancing quantum readiness and AI innovation.

by Heather Croft | Dec 3, 2025

BC offers a thriving environment for science co-op students where your work can contribute to food security, sustainability, and global trade. Whether your interests lie in agritech, greenhouse innovation, or value-added food manufacturing, this sector is full of opportunities to learn, grow, and make an impact.

For undergraduate science students exploring co-op opportunities, BC’s agriculture and food sector is more than farms and fields, it’s a $19-billion industry driving innovation, sustainability, and global trade.

With 74,000 jobs already in place and ambitious targets to grow exports by 25% over the next decade, this sector is opening doors for students interested in agritech, food science, and climate resilience.

Why It Matters for Students

For co-op students, this growth translates into:

- Placements in food-processing labs, agritech startups, and greenhouse operations

- Opportunities to work on climate-resilient agriculture and food security projects

- Hands-on experience in value-added manufacturing and global supply chains

Building From Strength

- $19 billion in revenues annually

- $6 billion in exports to global markets

- 32,000 businesses supporting communities across the province

- Food and beverage manufacturing makes up 65% of sector revenue, making it BC’s second-largest manufacturing industry

This foundation is being strengthened by major investments in dairy, greenhouse production, and food processing. All this is creating new opportunities for students to contribute to innovation in agriculture.

What’s Happening Now

Recent expansions and projects are reshaping the sector:

- Vitalus Nutrition and Punjab Milk Foods (Nanak Foods) expanding milk protein and plant-based manufacturing

- Greenhouse sector growth in both capacity and diversity of crops

- Project AgriGuard: a $382-million rendering facility boosting domestic and international export capacity

These initiatives are creating new pathways for careers in food science, agritech, and sustainable production.

Goals for the Next Decade

BC’s agriculture strategy aims to:

- Create new opportunities in agriculture, agritech, and food processing

- Leverage a 17% increase in dairy production to expand value-added milk and plant protein manufacturing

- Increase greenhouse production to meet rising demand

- Build an environment that reduces costs, supports scale, and improves affordability

- Expand exports beyond the US by 25%

The Bigger Picture

Over the past two years, the province has invested more than $300 million in food security, climate resilience, Indigenous food sovereignty, and supply chain improvements. A new $496-million plant and animal health centre in the Fraser Valley will further protect food supply, public health, and export markets.

With rising global demand for safe, sustainable, high-quality food, BC’s agriculture sector is positioned to drive inclusive economic growth and innovation, and students have a chance to be part of it.

by Heather Croft | Dec 3, 2025

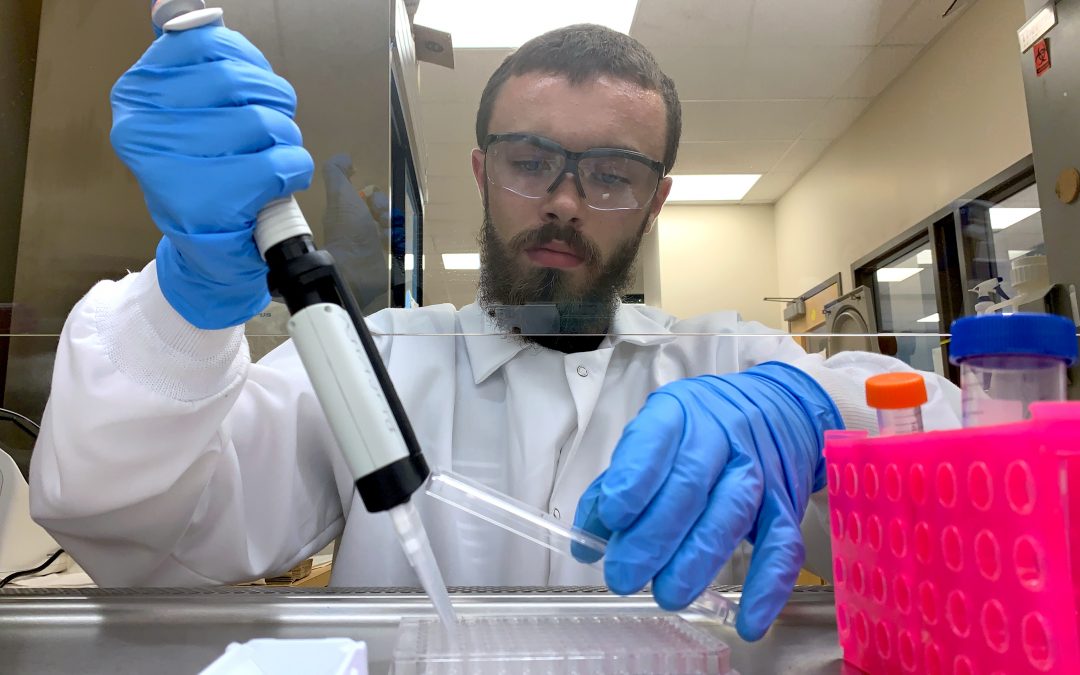

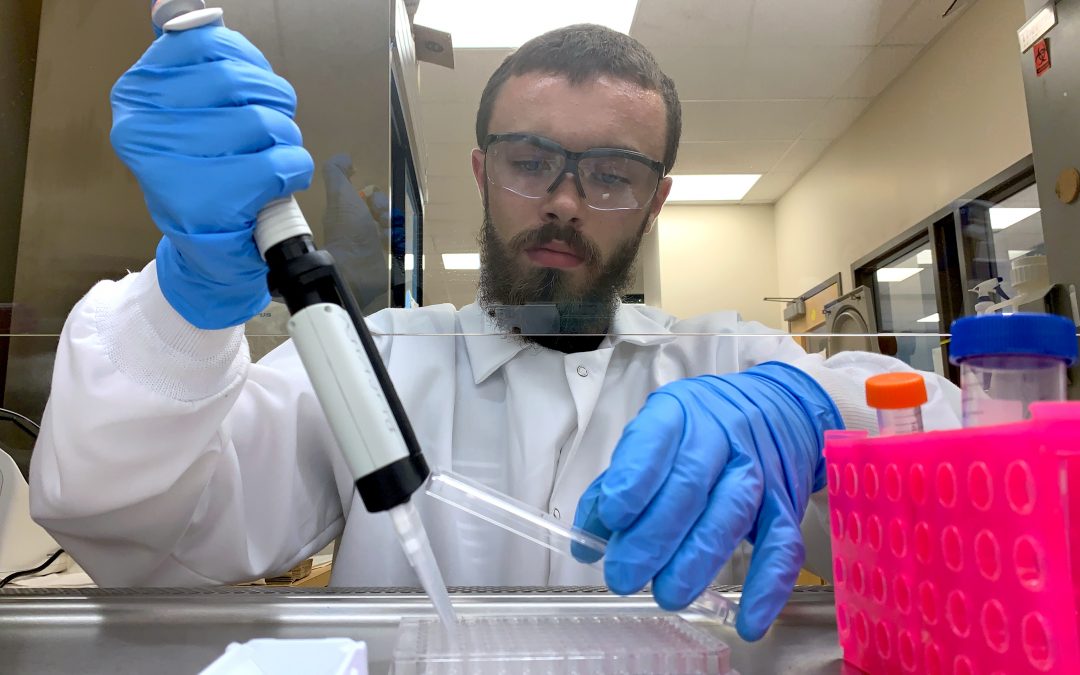

BC’s life sciences sector is one of the most exciting places to launch your career. Whether you’re passionate about biomanufacturing, clinical trials, or data-driven health solutions, this sector is full of opportunities to learn, grow, and make an impact.

Over the next decade, BC is aiming to boost its life sciences economic impact by 75% and double employment to 40,000 jobs. This means more opportunities for co-op students to step into cutting-edge research, biomanufacturing, and health innovation.

Why It Matters for Students

For co-op students, this growth means:

- More placements in labs, biotech firms, and research organizations

- Opportunities to work on global health challenges and emerging technologies

- A chance to contribute to projects with real-world impact, from pandemic preparedness to cancer therapies

Building From Strength

- BC has the fastest-growing life sciences sector in Canada

- 2,000 companies employing 20,000 workers

- $1.7 billion in leveraged investment fueling growth

This momentum is built on decades of foundational research and a track record of success: B.C. companies have contributed to 22 therapeutic innovations approved for patient treatment in the past 25 years.

What’s Happening Now

The province is investing heavily in:

- Research funding and commercialization projects

- Advanced biomanufacturing capabilities

- Infrastructure like wet labs and training facilities

These investments are creating a stronger ecosystem for students, researchers, and companies to collaborate and innovate.

Goals for the Next Decade

B.C.’s Life Sciences Action Plan sets ambitious targets:

- Establish an advanced mRNA and lipid nanoparticle hub for biodefense

- Expand expertise in nuclear medicine

- Grow clinical trials infrastructure and capacity

- Increase access to capital for life sciences companies

- Leverage anonymized health data to accelerate innovation

- Double employment to 40,000 by 2031

The Bigger Picture

With over $815 million committed by the provincial government and $1.7 billion in federal and private investment, B.C. is positioning itself as a world-class hub for life sciences and biomanufacturing. International investors and pharmaceutical firms are already taking notice, making this a sector where students can grow alongside groundbreaking innovation.

by Heather Croft | Nov 19, 2025

Rows of trees

On our way to the block we pass by the rows and rows of trees that will support our needs and are waiting to be replenished.

Mobile showers

There was always a trick to getting hot water or the right pressure to enjoy a nice shower after a hard day’s work.

A storm brews over camp

The rain came down hard enough that everyone scrambled to ensure the water wouldn’t flood the whole tent, mainly trying to protect the treasured charging station that kept our electronics somewhat accessible.

Red moon

Through the trees you can see a reddened moon next to our trusty small bus that packed planters and gear over hundreds of kilometers.

Blackflies

The effects of blackflies after they were brought out by a rainy day.

Cold days

We are preparing for a windy day with cold temperatures, sporting our beanies and jackets.

Essential gear

My purple shovel named Violet, my flagger pouch, my personalized hard hat and my dependable planting bags that helped to carry thousands upon thousands of trees to their home for the foreseeable future.

The effect of wildfires

On a day off, I drove into town but not without catching a glimpse of the effect of wildfires, the very same that had wiped out some of our camp’s previously planted blocks.

Flower picking

A block that was mostly swamp and rock, lined by a shallow lake. My crew boss picks flowers to bring up morale for the crew.

Ribs

This is the spine and ribcage of a young moose, found near an in-land cache.

Smokey block

Through the bushes you can see a smokey block full of poplars and residuals waiting for their next round of jack pine and black spruce to grow.

Shrine

A “shrine” built by one of my close friends that was originally used for leading walks in the woods by lighter light and creating a space for us to share our thoughts, hopes and dreads throughout the season.

Rain days

A little colour can go a long way for seeing your crew and morale.

Complete PPE

Mid-way through planting a tree, you can see the slash and debris from the previous logging cycle on the ground.

A dip in the river

The first camp in Manitoba has the most beautiful river, home to a beaver and a perfect place to rinse off the residue of the day.

Tiny toad

A testament to how delicate the ecosystems we plant can be, a tiny toad rests in my glove.

A night at Marchand Bar

The owners set up an event just for us planters with a karaoke machine, a fully attended bar and pool tables.

Transport

One of the company vans, used for transporting planters, trees and gear on camp move days.

Mess Tent

Where we eat, hold meetings, laugh, chat, dance and play daily.

Rosy maple moth

A moth glows with its beautiful colours and soft wings upon my hand equipped with a wrist brace to prevent injury.

Skull

This skull was found by a fellow planter in her piece, finds like this help the work be more immediately rewarding.

The rocky ground

A road we walked on to reach our blocks. The ground is a bit discouraging but overhead the sky paints a picture in the true northern Ontario sense.

Tree pods

All lined up and ready to plant.

Tree planting is an experience that profoundly shapes one’s perspective on work, community, and the natural world.

While the job begins as a series of physical tasks measured by numbers and productivity, it quickly evolves into something much larger: a lesson in resilience, a practice in responsibility, and a direct connection to the environment. Each challenge, whether related to weather, insects, terrain, or long periods of isolation, serves as a teacher.

Throughout the season, I discovered strengths I had not realized I possessed, developed patience beyond my expectations, and cultivated a sense of purpose grounded not in immediate results, but in the knowledge that my efforts would contribute to long-term ecological and societal benefits. Planting a tree is, in essence, an act of faith in the future, and over the course of my first season, this philosophy became the foundation for my growth both as a worker and as a human.

The act of curating this photo essay has also been valuable as a tool for reflection. Revisiting these moments, some of them difficult, others beautiful, has helped me recognize how much I learned, both about tree planting and about myself.

This photo essay is more than just a collection of images, it’s a curated visual narrative that captures the full arc of my planting season. It offers:

by Heather Croft | Oct 20, 2025

As an environmental and sustainability co-op student working with the Prince Rupert Port Authority, Piper McWilliam did everything from monitoring the presence of invasive species to looking at underwater noise from passenger ships in the harbour, and so much more.

In this photo, she is conducting a vertical net tow to capture zooplankton in Todd Inlet. Sampling zooplankton is necessary to monitor for the larval stages of aquatic invasive species, such as European Green Crabs.

Monitoring water quality

As part of my co-op, I carried out ecological sampling and participated in local and national monitoring programs.

Throughout the summer I trapped and sampled zooplankton to monitor for aquatic invasive species such as the European Green Crab. I also sampled marine environmental water quality to look at the effects of development on the Skeena River estuary, and collected data on dustfall and wet deposition to monitor the effects of development on local residences.

I also had the opportunity to support ongoing biological monitoring and took on new sampling projects such as underwater noise collection for large passenger ships in the Prince Rupert harbour.

Throughout the summer, I wrote and published information campaigns to encourage Prince Rupert Port Authority staff to engage with port environmental initiatives, compensation project updates, and even local species identification.

I also conducted research on new green initiatives and restoration projects to be shown to the executive committee in the early fall.

These projects will help the Prince Rupert Port Authority to maintain existing green certifications like the Green Marine program and to secure ISO 14001:2015 certification.

Exploring biodiversity

In my final weeks as a co-op student, I had the opportunity to expand on an existing project and design an intertidal biodiversity forecasting model using seven years of historical data.

The goal of this project is to predict changes and trends in biodiversity over time, contribute to the Prince Rupert Port Authority’s ongoing species registry, and to hopefully inform future decisions of development around Kaien and Ridley Island.

Seeing the impact of my studies

Working with the Prince Rupert Port Authority allowed me to improve the skills learned through my time at UVic such as statistics, ecological sampling, and research.

I was fortunate in my time as a co-op student to be able to work with many port partners, departments, and even other summer students to learn new skills and have many new experiences.

I have developed competencies in intertidal species identification, scientific communication and public speaking, navigating and sampling in the field, and working on vessels. I feel that this experience with the Prince Rupert Port Authority has equipped me to tackle new challenges and find success in future coursework and opportunities at UVic.

The co-op advantage

I would wholeheartedly recommend co-op to other students who may be considering it.

Aside from an opportunity to gain school credit, co-op provides a chance to network with like-minded individuals in your field, gain new skills, have new experiences, and ultimately find your passion.

As an aspiring marine biologist, I am thrilled to have had the opportunity to connect with organizations like OceanWise, OceanNetworks Canada, Environment and Climate Change Canada, and many others.

My experiences in co-op so far have allowed me into some amazing environments from thriving intertidal beaches to bustling construction zones to even the engine room on a bulk container ship at anchorage.

I feel that my experiences so far with co-op have prepared me to handle challenges and find success in my future opportunities, and I am excited to see what’s in store!

by Heather Croft | Oct 20, 2025

When Neko Kasawski (she/her) was looking for her first co-op experience, she found the perfect way to get her feet wet.

The biochemistry an biology student spent the summer working as an assistant educator with the Shaw Centre for the Salish Sea in Sidney, BC.

This photo was taken in the “touch pool” area of the Shaw Centre for the Salish Sea, where Neko is holding a leather star.

This role involved leading educational marine science activities to connect visitors of the centre with local marine life. I assisted with school field trips, public outreach events, and public programming.

Engaging with visitors about the many amazing species that call the centre (and the Salish Sea) home was the most rewarding aspect of this job. I had the opportunity to teach people about our ocean and share in their excitement.

The impact of co-op

This was my first co-op work term and I am very grateful for the opportunity I had to immerse myself in local marine biology and gain experience in science education.

Co-op is an excellent way to come out of your degree already having good technical work experience under your belt. It is also a very valuable way to try out different work environments and find out what paths might interest you most.

by Heather Croft | Oct 17, 2025

mRNA and Nanomedicine Innovation in BC

BC is home to pioneering co-op employers and researchers who played a key role in developing COVID-19 vaccines and treatments:

- Acuitas Therapeutics continues to develop best-in-class LNP delivery systems, proven to be incredibly effective for mRNA Vaccines and next-generation CRISPR therapies.

- NanoVation Therapeutics is advancing LNP delivery for cardiometabolic and rare diseases.

- Genevant Sciences holds more than 700 LNP patents and maintains global pharmaceutical partnerships.

- Cytiva, formerly Precision NanoSystems, specializes in LNP formulations.

- Evonik Canada offers GMP manufacturing services for RNA therapeutics.

Overall, B.C. is positioning itself as a launchpad for next-generation therapeutics and vaccines, with a focus on scalable, sustainable innovation in life sciences.

by Heather Croft | Sep 24, 2025

Safety first!

Throughout your time with Co-op you may be exposed to workplace environments and materials that have the potential to cause harm if you are not adequately prepared.

To best support a safe Co-op (and beyond!) experience, you can complete an optional course in Workplace Hazardous Materials Information Systems (WHMIS).

This is a free, not-for-credit, online course.

How to Complete the Training

- Click Register to start.

- Work through the WHMIS Training Module.

- After working through the module, complete the WHMIS Training Quiz. You have 3 attempts.

- Once you have scored 80% on the Quiz, log in to Learning Central and Collect your certificate. Your certificate of completion will be emailed to you.

- After you complete the WHMIS course, remember to update your resume!