Introduction

The photos, text and audio clips in this section express the research participants’ thoughts on all three research questions presented to them: 1) What are your perceptions of old age in contemporary society as typically depicted in the media and popular culture? 2) What does old age actually look like to you, irrespective of what society and media depict as old age? and 3) How would you like old age to be portrayed in media and popular culture? There was similarity in the discussions around frailty in older age by participants in both groups of younger and older adults. In general, both groups objected to the most common model of aging and old age that is promoted by media and popular culture: the image of the ‘physically frail and/or cognitively impaired elderly’ person. While there is frailty in older age, participants felt that this very prevalent and stereotypical image is not equally balanced by images in film, TV, or print media that portray older people as active and engaged in life. All but one participant in the older age group and all of the participants in the younger age group commented on the stereotyping of older adults. In addition, all 11 participants in the older group and 4 out of 5 participants in the younger group were very concerned about the focus of media and popular culture on illness and decline in old age.

Discussion - younger age group

The responses from the younger group of participants around frailty concentrated on two topics: 1) the representation by media and popular culture of old age as frailty (or passivity) as the number one model of old age; and 2) the societal and family influences that shaped their perceptions of frailty and decline in older age. All five participants in the younger age group acknowledged that frailty (and/or passivity) were the most common stereotypical images of old age reflected in media, with the other two being: the ‘wise woman or man’ and the ‘Freedom 55’ image, (which will be discussed in the next section on ‘Gender and class – bias and inequality’). They all rejected the stereotype of older age as frailty and/or dependency. One participant felt that all stereotypes should be replaced by “nuance, dimension, and vibrancy.” Still another participant found it difficult to create images for the 3rd question as to how old age should be represented in popular culture, because although she was opposed to stereotypes, she also believed that old age should not be represented as “anything” by media or popular culture. Instead, because old age has many faces, it should be shown through a multitude of interpretations and images, just as any age is presented in varied and individual ways. However, she did suggest that highlighting positive intergenerational relationships would help to generate a more constructive image of aging. Her comments on the importance of intergenerational relationships have resonance with academic discussions and articles on the detrimental effects of the social separation of young and older adults in modern industrialized society, as well as the benefits of positive intergenerational relationships (Hagestad & Uhlenberg, 2005; Cadieux, et al, 2019). In addition, this same participant felt that media had a responsibility to show that health problems can come at any age, not just old age. One of the responses by a male participant echoed her opinion. He believed that focusing on frailty in old age should be avoided as illness and death can come at any time, plus people face their health challenges in different ways: “Older people are individuals and all age differently.” Considering the question from a completely different perspective, one male participant felt that because he was not yet an older person it would be presumptuous of him to suggest how old age should be portrayed in media and popular culture, and instead should be decided by people in the older age population who were being represented.

The responses from both participant groups very often came out of their own life experiences in their families. Within the younger age group, one female participant’s awareness of frailty in older age grew out of her personal experience and knowledge of frailty and serious illness in her family background in which poverty, chronic health issues, and early death were the reality for many family members. She also had a very keen awareness of the class inequality embedded in this situation. Another female participant’s perspective of frailty was formed through positive interactions within her large intergenerational Middle Eastern family. Because of the support and interdependence within her family for family members who experienced ill health or hospitalizations, she had not developed a fear of frailty and old age. The other female participant also had a positive outlook on older age connected to personal experiences and role models provided by active and healthy family members in their 60s-80s. Consequently, she found the media portrayals of older people as passive and sedentary very untrue and insulting to older adults (and to the general population). She felt that these representations were harmful and should be replaced by media images, and film and television depictions of the older population engaged in a wide variety of physical activities that were common to all age groups. One of the male participants formed his opinions on aging largely through personal relationships with people, young and old, some of whom had dealt with chronic health issues and physical limitations, yet he witnessed them handling their issues with a positive attitude and living productive and healthy lives as best as they could. Consequently, these experiences may have influenced his point of view that how each person deals with aging is a matter of personal choice. With a critical eye on media, the other male participant discussed the negative impact of seeing numerous pharmaceutical ads on TV for dementia medications when he visited his family in the US. These ads, combined with seemingly constant news clips about dementia on mainstream TV networks, such as Fox, spread anxiety and fear about dementia. He found that he was not immune from the effects of these advertisements.

Academic literature reflects the observations made by some of the participants about the rewarding effects of intergenerational relationships and positive interactions with older adults can have on our own attitudes about age and aging (Cadieux, et al., 2019; Babcock, 2016; Gullette, 2004). Although positive benefits of family relationships were noted by the majority of the participants, one male participant also described how his attitudes toward the aging process were negatively impacted by his mother and aunts who used numerous anti-aging products and services in their almost obsessive quest to remain “youthful.” As a result of his exposure to this culture of staying young, combined with the barrage of TV ads on dementia he experienced when he visited his family, he internalized a fear of aging at a relatively young age.

Discussion - older age group

The majority of the older group of participants were very concerned about the primary media representation of aging as frailty and decline. Included in this stereotypical model of old age are depictions of dementia, loneliness, incompetence, and dependency. Participant insight on this topic is also mirrored by academic research on aging and older age over the last two decades, which suggests that the negative stereotyping of aging as physical and cognitive decline is still a pervasive model of aging in North American society (Binstock, 2005; Revera Report on Ageism, 2012; Higgs & Gilleard, 2014), while other negative stereotypes have been added over that period of time which include: mental and technological incompetence; having a grumpy and unpleasant personality, and being socially and politically conservative (Revere Report on Ageism, 2012; GDIGM, 2020). According to one of the male participants, the image of older people as frail, passive and vulnerable is passed on to society, where it is absorbed and internalized by the general population, so that even when we become seniors ourselves, we perceive old age that way too. This same participant also said: “By presenting the image of aging in this way it also encourages the belief that older people have less value, and less use to society than they did when they were younger,” which is another form of ageism. Popular culture and media, he suggested, have a bias towards youth who are active and seen as productive because they are employed, making them valuable within our neoliberal society as both a worker and a prime consumer.

His perspective is also reflected in the literature on ‘individualism’ and ‘neoliberalism.’ There is another significant influence that affects our perceptions about aging and fuels ageism – (Hooyman & Gonyea,1995; Gullette, 2011). The ideology of individualism that is rooted in the 19th century emphasizes self-reliance, independence, and productivity, while negatively characterizing any form of weakness or dependence (Harvey, 2005; Hooyman & Gonyea, 1995). Building on the ideology of individualism, neoliberalism contributes to the belief that to have value as an older person in our society, you must continue to be healthy and productive and/or have enough wealth to maintain complete independence. And applying individual ‘choice’ and ‘personal responsibility’ (two of the primary tenets of neoliberal ideology) are the methods to use to achieve this state in old age. But if you should instead become a frail and dependent older person any value you might have is removed, thereby translating into the ultimate form of ageism.

This question of who has value in our society has been highlighted and pushed into the public’s eye during the current COVID-19 pandemic. In the early stages of the pandemic, outbreaks in long-term care facilities (LTC) across the country resulted in large numbers of deaths of vulnerable and frail older adults. An article in the BC Medical Journal in August 2020, stated that: “Deaths from COVID-19 have disproportionately affected seniors living in LTC. Only 1% of Canadians reside in LTC, but these deaths represent 80% of all COVID deaths in Canada” (Chung, 2020). A question that we might ask is why this unacceptable situation was allowed to happen to our most vulnerable population in the first place. I would suggest that the answer to this leads back to ageism. Who (and who does not) have value in our society? The frail and dependent elderly it would seem, clearly do not. We also need to ask ourselves: How can this situation be changed?

Looking at frail older age from another perspective, one participant, along with five other participants emphasized that the seniors she knows are active and engaged people and should be shown in this way in popular culture and not as frail and weak. From her point of view, there are two categories of older age: younger old age, represented by adults in their 60s who are still active and independent; and older old age, which is not defined by years but by level of independence and ability to continue to participate in active living. Media and popular culture, she said, present all old age as older old age, which has not been her experience. Although this participant’s comments reflect critical thinking and good observation skills, like the rest of the population in our culture she has been inundated with constant negative images of aging over her lifetime and has most likely internalized some of images of the “ideology of decline” (Gullette, 2004). As a result, she may also be trying to distance herself from the frailties of old age, and instead focus on the positives of older age.

Her descriptions of the two age group categories and her reactions to the negative media depictions of old age mirror the academic debates around categorizing aging which have taken place for several decades, as there is now a designated ‘third age’ (presently represented by the boomer generation), followed by the ‘fourth age’ (or the oldest old). Some scholars have argued that the influence of the successful aging model supports a perspective that views aging in a negative light, consequently, creating even more fear and anxiety around the normal aging process (Kaufman, et al, 2004). Where previously ‘old age’ may have been conceptualized as age 60+ or 65+, the model of successful aging has not eliminated the stigma or negative associations of ‘old age,’ it has merely shifted the definition of “old” to an older age category where frailty resides—the fourth age (Higgs & Gilleard, 2014, 2019; Bytheway, 2005).

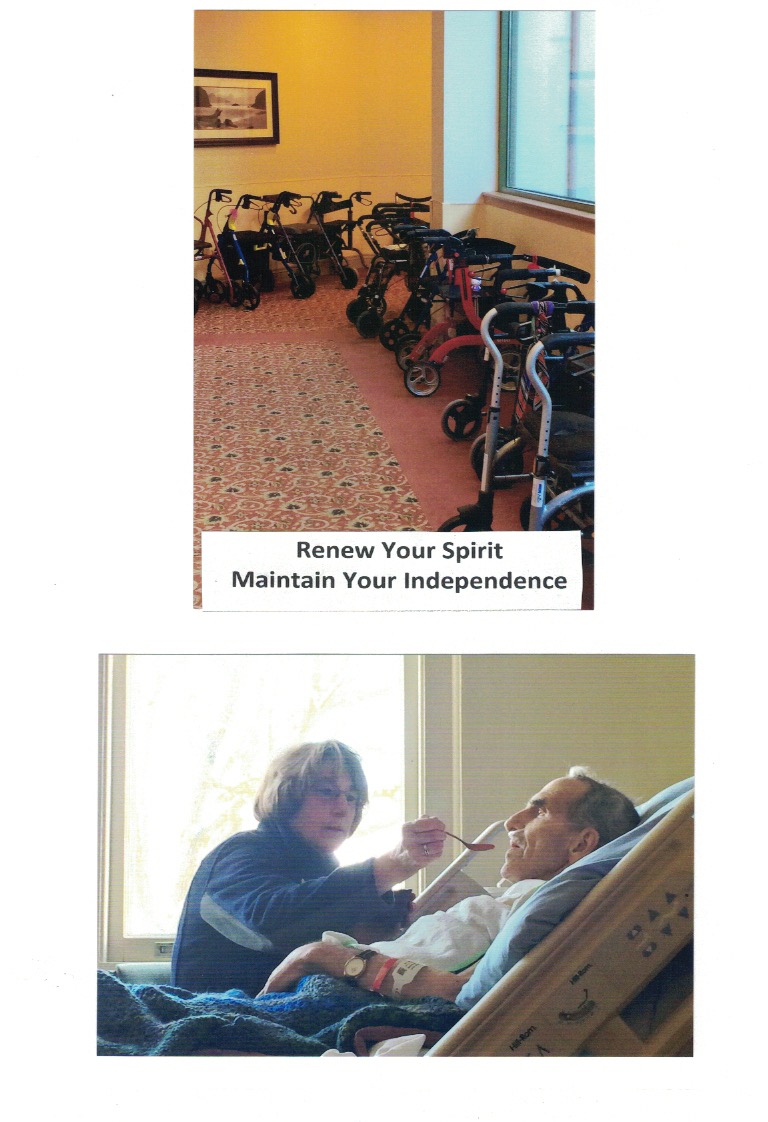

Turning to popular culture, one of the female participants suggested that media and popular culture reinforce our cultural fear of death and frailty with their depictions equating old age with physical and/or mental frailty, while at the same time they provide escapist entertainment and distraction through film and TV programs. One of the participants in the younger group also mentioned how lifestyle reality TV programs function as a distraction to the realities of everyday life through their focus on the lives of the rich and famous. Print media in the form of seniors magazines, on the other hand, has a strange mixture of feature articles on celebrities of one kind or another, anti-aging ads that target the affluent older adult (from upscale retirement home living and exclusive senior travel to ads for services and procedures to prevent or slow down aging), as well as ads that target the frail older adult (mobility aids, dementia medications, incontinence products), while still avoiding as much as possible, articles that are specifically about death or dying. This same participant also pointed out that media focuses on extremes and appearance rather than on the inner life of older adults and human values.

The older group of participants also discussed the influence of personal (family and work) experiences on their attitudes about older age. Two female participants discussed the positive influence of growing up within a close intergenerational family context, while one of the male participants discussed the inspirational effect his parents had on him, providing him with role models of old age. They had a healthy and happy long life together, always finding ways to enjoy life that they passed on to him. One of the female participants emphasized the importance of maintaining a positive attitude throughout life and adapting to its challenges. She talked about older people she knew, who although being low-income seniors who needed mobility devices to get around, cared for pets, engaged with their communities, and generally enjoyed life. Her thoughts reflect academic research from the Netherlands (where she grew up) that pointed out the contrast in the perspectives of seniors in North America and the Netherlands. In North America, successful aging is associated with remaining healthy and independent; whereas seniors in the Netherlands believe that the secret to successful aging lies in “adjustment” to the variety of challenges of old age (Von Faber & van der Geest, 2010).

A majority of the older group of participants (6 out of 11) also recognized that a level of frailty in older age is the reality for most people, but also expressed concern that there is a lack of popular culture and media representation of older people as active and engaged in life. Instead, the most prevalent media portrayal of ‘old age’ is still the stereotypical image of the ‘physically frail and/or cognitively impaired elderly’ person. Old age is not one thing. Frailty is often a part of it, but so is active and healthy living, intellectual and creative engagement, volunteering, spending time with friends and family, and many other things.