We all met at Nick’s apartment on the 24th of November at 11 am to start our medieval meal. Nick had made bread and beef stock the night prior, and thankfully so, as they were both time-consuming and labour-intensive. Since meat dishes usually take the longest, we started with the cinnamon brewet. We quartered the meat as instructed, then sautéed (seared) it in a hot cast iron pot, and added the wine and beef stock to deglaze.

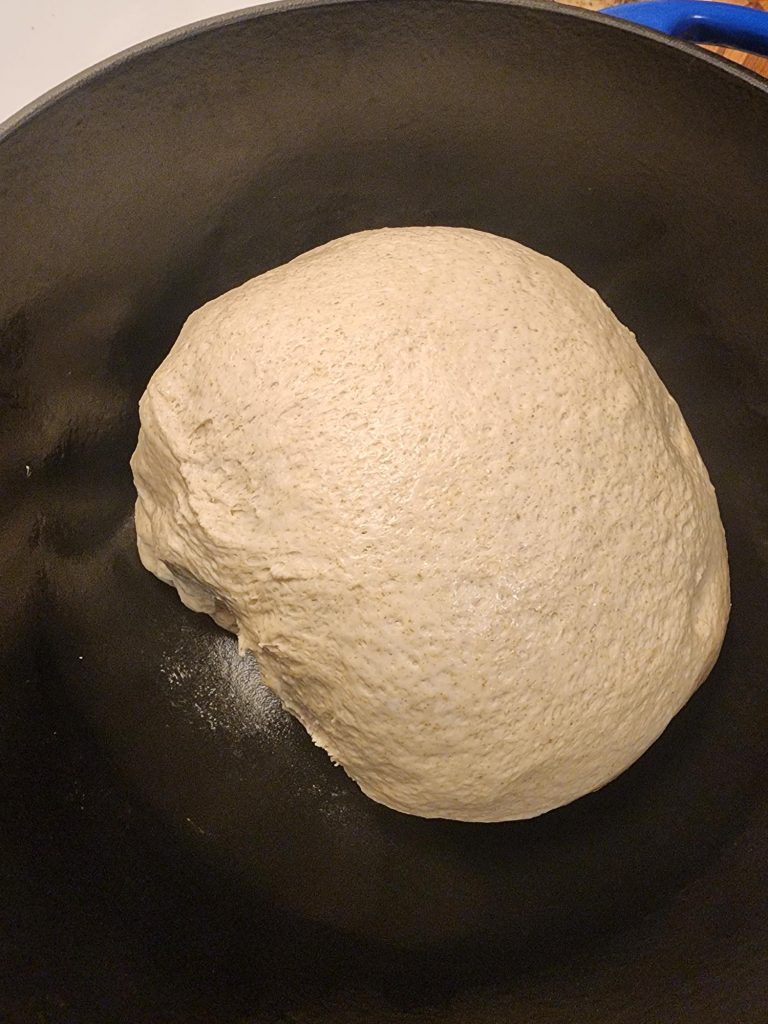

The Bread

In the meantime, we ground the almonds with a food processor, but we were then stumped by the following instructions. The recipe told us to: “grind unpeeled, dry almonds, and a great deal of cinnamon, moisten them with beef broth and strain them, boil them well with your meat.” Confused, we decided to ignore the section of the recipe telling us to strain the almonds. We then added to our pot all the other spices (ginger, cloves, cinnamon, and grains of paradise) and the red wine vinegar, which was our substitute for verjuice (unripe grape juice). This was left to simmer for three hours, and we added a bit more liquid to the brewet once or twice.

The Cinnamon Brewet

Anjuli started mixing spices to make the poudre douce. Since the galangal was extremely dry and impossible to crush, we improvised and decided to soak a few pieces in hot water. Once they had absorbed some of the water (enough to ease processing), we finely diced up the galangal and crushed it as best we could. When it resembled a rough paste, we put it in the oven for about fifteen minutes. When we removed it from the oven, it was completely dry and ready to be scraped into the mortar with all the other ingredients: ginger, sugar, cinnamon, nutmeg, and grains of paradise.

The Alligator Pepper Pods, the Galangal, and the resulting Poudre Douce

We boiled water for the almond milk (ground almonds) and barley water (barley and sugar). After waiting fifteen minutes, we strained the almond milk through a cheesecloth and funnelled it into a large glass. The process was messy but yielded a nice, thick almond milk for the fridge. The barley, sugar, and hot water mixture was then placed to boil over the stove until the barley burst. After straining it, we chose to serve the barley water hot.

The Almond Milk

The Barley Water

Now that we had the almond milk, we started our apple muse. We peeled, cored and diced two apples and simmered them in water. Once the apples had softened, we crushed them and added the honey, sandalwood powder, saffron, salt, almond milk, and breadcrumbs made from the bread that we made the previous week. All of this together made a reddish, thick apple paste.

The Apple Muse

We prepared another pot with beef stock and halved turnips to simmer until soft. We then cut the turnips into quarter-inch slices to fry in a hot cast iron skillet with butter and seasoned generously with poudre douce.

The Turnips

By this point we were all hungry and ready to dig in, so we plated each dish and gathered around the table to dish ourselves up. After hours of cooking, we were excited to taste the fruits of our labour. Our ratings and reflections on each dish will be posted in a later blog.

Our meal may not have been entirely authentic due to the ambiguity in the written recipes and the use of modern cooking implements. That being said, we did get a good idea of what kind of flavour profiles were present in Late Medieval France.