New craft for Spring 2023

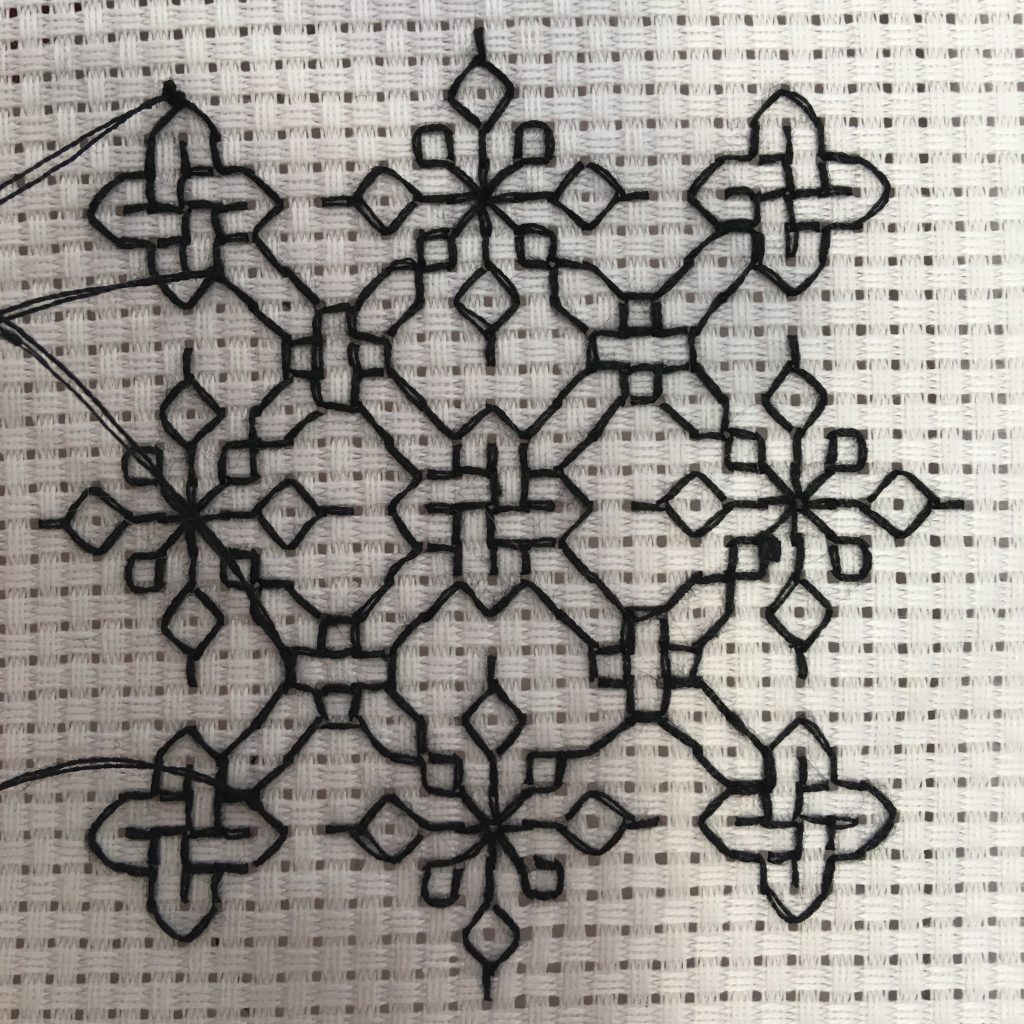

Our new craft for Spring 2023 is a type of embroidery known as “blackwork”, which can be analyzed using the tools of graph theory in an interesting way!

The name “blackwork” comes from the fact that typically this type of embroidery is worked in black thread. It was very popular in 16th century England (where it was also called “Spanishwork” due to a mistaken belief that Catherine of Aragon had introduced it to the country). When worked in red thread it was called “scarlet work” – you get the idea!

Blackwork embroidery is what we call reversible embroidery, meaning that it looks nice on both sides of the fabric (although naturally the pattern is mirrored):

Compare this with something like cross-stitch, which can be really messy on one side of the fabric.

In order to produce a nice-looking, tidy, and efficient piece of embroidery you want to make sure no stitches are duplicated. In other words, for each segment of your pattern you want to have exactly one stitch on each side of your fabric – no doubling up! The mathematical question then arises: what patterns can be embroidered in this way with a single (possibly very long) piece of thread? It turns out that this question can be answered with graph theory, and if you are interested to learn more here is a paper about it: The Graph Theory of Blackwork Embroidery, by Joshua Holden.

Warning: graph theory!

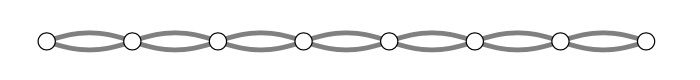

Briefly, we will represent the pattern with a multigraph by adding vertices where the holes in the fabric would be and by adding two edges (one for each side of the fabric) where the pattern says stitches should be. The multigraph below represents a very boring pattern – just a straight line that is seven stitches long!

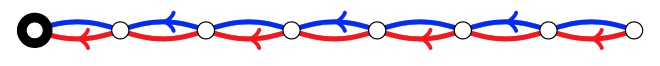

When embroidering in a running stitch, we alternate sides of the fabric. That means we want to find an Eulerian circuit (one that traverses each edge exactly once) with the additional property that if the circuit’s edges alternate red/blue then the graph as a whole will have exactly one red and exactly one blue edge for each original stitch in the pattern. The red stitches then produce the pattern on one side of the fabric, and the blue stitches produce it on the other. The directed blue and red edges below illustrate what happens if you do a running stitch along our boring pattern from the leftmost side to the rightmost side.

If we stopped there, we would have a dashed line (blue edges) on one side of the fabric, and a complementary dashed line (red edges) on the other. To complete the embroidery, in this case, you can simply continue your running stitch back to the leftmost side.

I’ve shown you that you can embroider this particular pattern in this way (Holden calls this a Holbeinian circuit; I’ll say that the pattern is “blackworkable”). It’s not too hard to convince yourself that any length of path is blackworkable. After some trial-and-error you can probably work out how to blackwork embroider any cycle in this way too (the parity of the cycle matters a bit here; odd cycle have more options than even cycles do).

Holden proved that you can in fact embroider any pattern this way as long as it is connected! At one of our Maths & Crafts gatherings in February, we worked through the proof of why this is true.

Resources

Holden’s original paper (preprint) https://www.rose-hulman.edu/~holden/Preprints/blackwork.pdf

Making Mathematics with Needlework: Ten Papers and Ten Projects, edited by sarah-marie belcastro and Carolyn Yackel, has this example and more.

https://www.blackworkarchives.com is a good source of historically inspired blackwork patterns. Be warned that some of them are not connected and will require more than one piece of thread! For practical reasons, you would usually want to use more than one piece of thread anyway, becausevery long threads tend to tangle.