Community Capacity Building Portfolio

The meaning of community is “… the potential embodied in the connections between people at the local level, connections that, in some circumstances, can be obscured and even destroyed by a traditional “service” orientation”

(Hodgins, personal communication, 2018)

The following body of work is an integration of key theoretical and practical approaches to community capacity building in early years settings explored in the University of Victoria (UVic) Child and Youth Care (CYC) 480 course, Advanced Applied Capacity Building for the Early Years. The work is structured around themes of

- the importance of relationships,

- the conditions necessary for community capacity building,

- the role of early year’s settings in community capacity building,

- the benefits of a two-way dialogue between minority and majority world communities in the promotion of community capacity building,

- and the impact of assimilative practice and policy on community capacity building and possibilities for indigenous renaissance in the 21st century (Hodgins, personal communication, 2018).

The Importance of Relationships

Relationships create shared knowledge. In early years settings I align with Rinaldi’s (1993:05) description of the rich child where learning is communicative and cooperative and children are active co-constructors of knowledge, making meaning of their world (cited by Dahlberg, Moss and Pence, 2013). As a practitioner, one is often questioned on their personal theory of child development, which immediately problematizes itself with its own question. A colleague in the course explains:

Child development

Wednesday, 10 January 2018, 2:31 PM

If we have a predetermined interpretation of development and progress (which may look different for different people, but is valued nonetheless), it may demerit the experiences of those who do not fit within that interpretation. Collaborating with children and families to identify their perception of growth and development will allow me to facilitate the change they wish to see within their lives, rather than imposing the dominant story.

What is the dominant story she refers to? According to Dahlberg et al., it is a narrative that tells a simple story where prescribed practices “… applied to children at a young age will achieve prescribed outcomes in later life” (p. vi). These practices have been labeled as child development. Circumventing euro-centric constructions of child development where “We have functioned as a field as if all children would be better off if their parents and teachers understood child development” (Cannella, 1997, p. 45) requires wisdom to be gathered and passed to one another in different ways. Childcare workers need to shift their understanding of child development to a place that recognizes it has been constructed by specific people with power over other groups and does not act as a truth that should be applied to all younger people; Cannella describes child development as “…a set of beliefs that have been constructed within a particular social, political, cultural, and historical context”.

Frameworks of practice describe and organize these sets of beliefs. The National Association for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC) is an organization from the United States representing early childhood educators, and is responsible for the Developmentally Appropriate Practice Programs which, according to Lubeck (1996), produces guidelines that use a “… decontextualized approach, ‘premised on modernist assumptions’, ‘serves to foster the development of an isolated being … with the end goal being the autonomous individual’ (cited by Dahlberg et al., 2013, p. 105). The following colleague’s post reflects on comparing two frameworks for practice, the NAEYC and our local British Columbia Early Learning Framework BCELF).

Re: Combatting DAP with Dialogic Processes

Monday, 26 February 2018, 11:32 AM

Whilst both the NEAYC and the BC Early Learning Framework contained developmental theory components, the manner in which they presented those components varied considerably. The NEAYC adopted an ‘expert’ approach and presented them as guidelines for ‘quality.’ The BC Early Learning Framework, on the other hand, presented them in the form of questions, providing space for multiple answers. The latter reflects an understanding and appreciation for culture and context. I strongly believe that asking questions rather than imposing a single answer provides space for the dialogic process you referred to.

The following table, taken from the class co-constructed WIKI, compares these two frameworks, illustrating differences in spite of similar goals to support children’s best interests.

|

THE IMAGE OF THE CHILD |

|

|

BC Early Learning Framework (see p. 8) |

NAEYC Developmentally Appropriate Practice |

| capable | capability is dependent upon child’s age, and knowledgeable teachers can predict this (p. 9) |

| full of potential | teachers know what strategies will promote a child’s optimal learning and development |

| having complex identities | “specific groups of children and the individual children in any group always will be the same in some ways but different in others” (p. 9) |

| grounded in individual strengths and capacities | “… teachers make plans and adjustments to promote each child’s individual development and learning as fully as possible” (p. 9) |

| unique social, linguistic, and cultural heritage | Teachers need to consider circumstances such as living in poverty or homelessness, having to move frequently, and other challenging situations |

| recognizes children’s ability to access knowledge through interaction with rich, supportive environments where relationships with family and community, language and culture, and their surrounding environment inform them to build knowledge collaboratively | “… curricular guidance gives teachers some direction in providing the materials, learning experiences, and teaching strategies that promote learning goals most effectively, allowing them to focus on instructional decision making without having to generate the entire curriculum themselves” (p. 6) |

Working with this understanding, collaboration is key to relationship building and McKnight (1995) tells us “There are incredible possibilities if we are willing to fail to be gods” (p. 604). This statement indicates that a change in approach to understanding how to care for one another can open a door to developing different relationships within communities. An example of this change can be seen in the Reggio Emilia approach where Hodgins (personal communication, 2018) describes,

In Reggio Emilia, teachers are not conceived of as “experts on childhood,” but rather as researcher-practitioners engaged in ongoing critical inquiry into who children are (Rinaldi, 2006). The “knowledge” teachers bring to this process is not so much textbook-based knowledge of child development and age appropriate practices, but rather the capacity to respond to children “in the moment,” which might often require setting aside limiting preconceptions about children’s abilities (p. 5).

Understanding of the dominant discourse took time to put into a manageable perspective, where I began to understand that thinking and ways of being do not change in an orderly, linear fashion. Spanos, describes this as, “an inherent mode of human understanding that has become prominent in the present (decentred) historical conjecture”. Current practices that endorse the dominant discourse are not ‘wrong’, they are in a place of being where they are at in relation to other ideas than the dominant discourse (Dahlberg et al., 2013).

An expansion of relationship-building contexts can be heard through the reflections of a guest speaker, Corine Sagmeister who is the Director of Aboriginal Stakeholder Engagement in the Early years Office of the Ministry of Child and Family Development (MCFD).

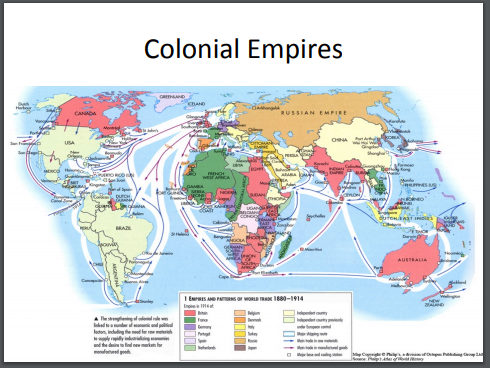

Ms Sagmeister’s work in community capacity building and her knowledge in rebuilding relationships is the result of colonial violence that continues to exist in Canada (Battiste, 2013).

UVic scholar Sandrina de Finney, a second guest speaker, is a researcher with the Siem Smun’eem Indigenous Child Well Being Research Network and speaks of relationship from an Indigenous perspective, reminding non Indigenous people of threatened connections between these communities.

You can read about this research network here, www.uvic.ca/icwr

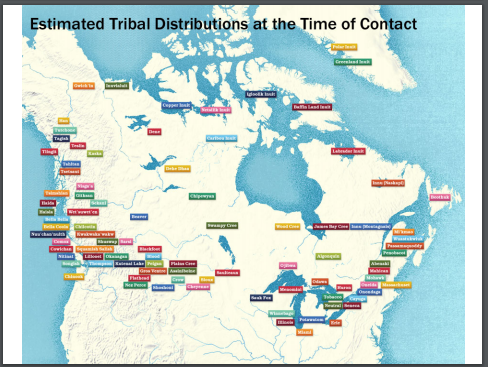

How do the Indigenous relationships Ms de Finney describes come to be seen so differently by non Indigenous people?

Conditions Necessary for Community Capacity Building

Relationship-building among local residents, associations, and institutions is one of three characteristics of community capacity building according to Kretzmann and McKnight (1993) alongside being asset-based and internally focussed. Investigating what that looks like in early years settings, it is important to consider Kretzmann and McKnight’s description of the three ccb components, individuals, associations, and institutions. McKnight (1995) goes a step further to describe “… characteristics of those social forms that are resistant to colonization by service technologies while enabling communities to cultivate care” as being uncommodified, unmanaged, and uncurricularized. (p. 603). A colleague refers to the Reggio Emilia approach in this regard:

Reggio Emilia

Monday, 29 January 2018, 5:43 PM

I believe that drawing from different stories is a valuable way to fuel discourse. It prevents the perpetuation of a single story and promotes community capacity in the sense that the knowledge is internally generated even if it is inspired by external sources. This idea of stories reminds me of Adichie’s (2009) presentation on the danger of single stories, and the value in being open to multiple stories in order to truly understand people and places:

https://www.ted.com/talks/chimamanda_adichie_the_danger_of_a_single_story

Dahlberg et al. (2013) reinforce her viewpoint with an explanation of Reggio and its ability to cause a crisis in thinking which creates a struggle over meaning and offers opportunities to view, in a new way, children as co-constructors of knowledge, early childhood institutions as forums in civil society, and early childhood pedagogy as creating a place where children can have the courage to think and act for themselves (p. 130).

A colleague describes an in-practice example of documentation practice and how its characteristics as uncommodified, unmanaged, and uncurricularized supported building a stronger sense of community in the group.

Re: Reflection on Guest Speaker’s experience

Sunday, 4 February 2018, 10:44 PM

When I did a Harvard course called Making Learning Visible, we did a lot of documentation to try and hear the individual voices of each child during challenging transition times of the day. One piece that we did, which really stuck with me was to individually ask the children to pair each other up in partners with pictures cards and tell us why. Children paired each other based on simple and complex ideas such as “they both like trains,” “they like to play together in the morning,” ” they sit together at lunch,’ “I think she’s pretty” and “they both have black hair”. It was amazing to see their perspectives of each other in the classroom and what similarities and differences there were in the children’s pairings. In our text book it says that “the work of the pedagogue consists largely of being able to listen, seeing and letting oneself be inspired by learning from what the children say or do” (p. 145). In our case, we were noticing the children feeling excited or disappointed based on their pairings for the day, causing potential struggles in our morning routine and wanted to get to the route of those emotions and figure out what was connecting the children from their perspectives. We then took those conclusions and involved the children as a whole group into the discussion, which connects to what you wrote about having the children have a say in sorting out the thoughts and questions we had. It is in these collaborative explorations that we build a stronger sense of community within a group.

This viewpoint reflects necessary conditions for community capacity building in the Reggio early years setting and is echoed in the BC ELF, described within a WIKI page designed in this course,

The British Columbia Early Learning Framework says that “the image of the child reflects not only a person’s beliefs about children and childhood, but also their beliefs about what is possible and desirable for human life at the individual, social, and global levels” (p.4). The document puts forth the image of a “capable child, full of potential, it is recognized that children differ in their strengths and capabilities” (p.4).

Edwards, Blaise, and Hammer (2009) use the term postdevelopmental to consider the questioning of modernist assumptions of truth, universality and certainty occurring in the early childhood education field. They describe an ageist discourse through a postdevelopmental lens in which “… all social interactions were seen as equally valid, difficult and/or stressful for all participants, regardless of their age…” and contrast it to a developmental one where it is assumed older children have harder work to do than infants and toddlers, and it is easier for the older children to socialize with the younger ones than with peer groups (p. 60).

A third guest speaker event introduced Sherri-Lynne Yazbeck and Ildiko Danis from UVic Child Care Services to interact with the class. Ms Yazbeck’s and Ms Danis’ descriptions of their backgrounds and experiences in practice describe viewpoints rooted in postdevelopmental principals.

Ms Yazbeck might be considered one of the thinkers Hodgins (personal communication, 2018) describe, who “… value debates on quality, not so much because of their potential to help define the concept, but because of the potential for such debates to engage citizens in the dialogic process of discovering what they want for children, what they want for their society, and what role child care institutions can play in promoting that society” (p. 6).

The conversation with these guests moved forward, fleshing out what their pedagogical practice looks and feels like in daily practice, making it clear they do not bring their passion to work, it is regenerated within their approach to practice. Their insight connects to Hope’s (2017) online reading from Australia where,

“What we are actually required to do is provide documentation that encourages us to be focused, active and reflective in our documentation and design decisions. Documentation should provide us with opportunities to keep track of our steps, not only to be able to reconstruct and communicate the pathways we took, but also to continue to progress and make new design decisions.”

Ms Yazbeck and Ms Danis offered these examples of documentation, illustrating Hope’s description of potential for making new design decisions while Professor Denise Hodgins describes the inquiry based practice and different types of relationship and inquiry taking place:

Ms Yazbeck and Ms Danis share experiences of what their inquiry-based practice feels and looks like.

An uncertainty exists as educators navigate co-constructing knowledge that is embedded within colonial constructions of knowledge. Guest speaker Sandrina de Finney generously supported wrestling with this question and voiced it as one of the current challenges in early childhood education.

Corine Sagmeister offered conditions supporting community capacity building from her point of view in three ways:

- As mentorship

- as making space for peer to peer connections,

- and in Indigenous contexts, connection to the land.

Early Years Settings

“… ‘good life’ questions might include ‘What do we want for our children?’ and ‘What is a good childhood?’ … the early childhood institution as forum provides opportunities to enter into dialogue with others about good life issues, and the possibility of searching for some measure of agreement without any guarantee of or need for finding agreement.”

(Dahlberg et al., pp. 82-83)

Conceptions of childhood are being explored, challenged, and experimented with in both the Minority (“Developed”) and Majority Worlds, and children are preparing to live in societies where skills in the dialogic process are a necessity (Hodgins, personal communication, Week 3, p. 4). According to Hodgins, multiculturalism is a part of today’s institutions for Canadian children as well as the country being “… charged with the opportunity and the ethical responsibility to support First Nations in the work of cultural regeneration”; early childhood settings have the potential to become places where children, parents, early childhood educators, and community members can acquire the knowledge to live creatively with this multiplicity (p.4).

Corine Sagmeister describes what community involvement looks like.

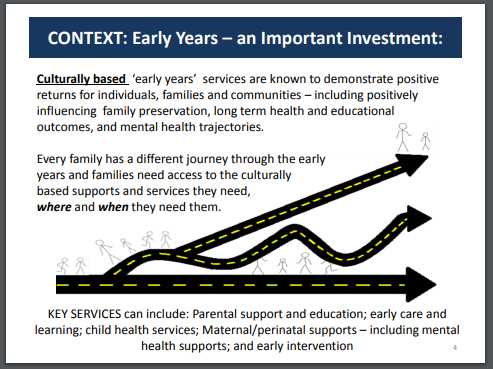

She goes on to illustrate the context of early years settings as important investments with positive returns for communities, and describes early years as playing an important role in Indigenous contexts, and describes the importance of relationship, relaying visioning with the community to design and develop Success by Six, involving nations, provincial and municipal government levels.

Rinaldi (2001) tells us the infant-toddler centre is a system of relationships that is for children although you cannot separate them from family and society. As social subjects, children are in school, in a place for the culture, where the culture is translated, and also where the culture of children and the culture of childhood is created (Rinaldi, 2001). Parent involvement is is an important part of that development and, according to McNally and Slutsky (2016), “… is a direct result of reimagined roles of parents as equally important to the overall educational experiences of children” and opportunties occur several times throughout the year where parents interact with the school (p. 1927).

A colleague cites a example of experience with family interaction in a different early year’s setting:

Re: Looking Inwards instead of Outwards: Gifts within the Community

Wednesday, 28 February 2018, 7:46 PM

I think it is important to give back to the parents and the community by supporting them and co-learning about their children with them. I have a great book from New Zealand titled “Te Whariki” that explains the connection to the family and the community relationship by stating “Children’s learning and development are fostered if the well-being of their family and community is supported; if their family, culture, knowledge and community are respected; and if there is a strong connection and consistency among all the aspects of the child’s world” (p.42). I believe that the more we learn about children and share with parents and the community, the more we have to give back and the stronger and more respected our field of early education will be viewed by the community.

Hodgins (2018) refers to the Te Whāriki (New Zealand’s national early childhood curriculum framework) as an exceptional example of cultural sensitivity, where its co-construction embraces diversity and establishes it as primary to high quality early years education (personal communication, week 8, p. 4). The document has a separate Maori component because the Te Kohanga Reo, or early year’s Maori language nests, had been in place for ten years which Hodgins describes as a key example of its transformative power to impact government decision-making in creating a national curriculum while promoting biculturalism within the country as a whole.

Canada does not have a national early years curriculum however, several provinces have been developing their own frameworks within the past decade including,

and most recently Newfoundland and Labrador.

(Hodgins, personal communication, 2018, week 2, pp. 6-7).

The BC ELF was released in 2008, heavily influenced by the Te Whāriki and it went on to partially inform the Australian government framework released the following year. Both the BC ELF and New Brunswick Early Learning and Child Care Action Plan drew upon New Zealand’s “Learning Stories” as assessment and evaluation approaches (Hodgins, personal communication, 2018, week 2, pp. 6-7).

Retrievable from https://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/education-training/early-learning/teach/early-learning-framework

Early years settings and the frameworks that inform them can act as powerful tools for community capacity building as reflected by a colleague,

Re: Child Development

Monday, 15 January 2018, 11:08 AM

In my opinion, early years institutions are places of power, and often hold particular knowledge about children, families, and communities. This isn’t necessarily good or bad. What I want to point out is that early years institutions are places that can shape how children, families, and caregivers think with children and child development (and for this comment, note that development refers to how children grow and learn in many ways beyond the dominant Western Developmental theory). I noticed that many of you stated that your views on child development have been affected by your work experiences. Therefore, early years institutions produce ways of thinking with children and child development.

I wonder then how early years institutions contribute or challenge dominant Western regimes of truth.

Sandrina de Finney speaks to the main point of disconnect between Indigenous worldviews and Western hierarchy.

According to Hodgins (personal communication, 2018, week 7, p. 2-3) thinkers in early years institutions recognize the strengths of non Western values while acknowledging poverty and socio-economic unrest due to colonial practices and policies against the Majority World. This balance needs to be maintained with the understanding that Majority World cultures are not static, have problematic elements, and work to repair the legacy of colonialism that often need to involve Western aid and influence. In this context early childhood programs become powerful constructs to transmit and reproduce cultural beliefs, values, and practices, where they can either build community capacity and cultural regeneration or serve to modernize Majority World countries through Minority World interventions that perpetuate the legacy of colonialism (Hodgins, personal communication, 2018).

In current practice in this regard, Sandrina de Finney responds to Denise Hodgins on how local needs and beliefs can be scrutinized to recognize the ability of children to understand our subversive history of colonialism.

Ms de Finney’s response brought to light a personal post describing a more nuanced understanding of Indigenous rights and society’s ethical obligation to uphold them.

Re: Ethical Engaged Effort.

Monday, 26 March 2018, 2:02 AM

Confusion exists over the difference between equal rights and upholding the rights of Indigenous peoples as laid out in treaty-making processes explained by Battiste (2013) where “The sale of Indian lands initiated in these treaties brought a settlement base for new settlers and Canada’s first treasury base. In all cases, Indians and Canada signed treaties in good faith to assist Indians in the changing landscape of settlement and provided lands for the new settlers” (p. 51). Rights for Indigenous people in Canada are different than simply equal rights. One of many alarming facts in the discriminatory, racist treatment of Indigenous people in Canada is not only the absence of their inherent rights as keepers and protectors of the land all Canadians reside upon, but the abhorrent lack of equal rights to non-Indigenous Canadians. I have often experienced discussions where people passionately declare Indigenous people in Canada do have access to equal rights and when I explain they are entitled to rights different from non-Indigenous people, there is a literal outcry of inequality. At this point dialogue about the truth of Canada’s shameful colonial history begins to take place.

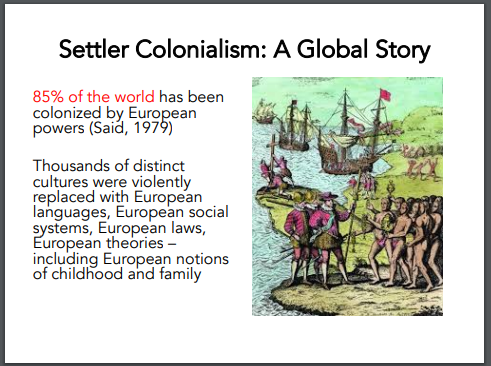

Benefits of a Two-Way Dialogue

Battiste (2013) describes a new transdisciplinary quest to balance European and Indigenous ways of knowing that is devoid of recognizing Indigenous knowledge as unique instead of different; unrecognized potential exists to discover new knowledge in the interface between the two. Varga (2000) describes how the colonization of childhood has take place since the second half of the 20th century, and taken form within the human and social sciences to be exploited and commodified (cited by Varga, 2011). This notion coupled with Battiste’s recognition of the holistic nature of Indigenous knowledge and its importance to Aboriginal people allows one to see how an Indigenous worldview has the potential to inform Western worldviews Varga (2011) describes as “… a process that makes development independent of the person, thereby erasing and distorting the cultural context of the child. Through scientific child study, development is disembodied from the person” (p. 154).

A colleague’s post describing her current practice returns to Battiste’s image of interface, or space between knowledges, exemplified by the Generative Curriculum model Hodgins (personal communication, Week 6, p. 7) describes as a partnership between the Meadow Lake Tribal Council of Saskatchewan and the UVic School of Child and Youth Care to develop a child care training program that would reflect the perspectives of the Cree and Dene communities within their jurisdiction.

Week 6 “The Generative Curriculum Model (…) is predicated on the assumption of that there are different but equitable sources of knowledge and ways of knowing” (Ball, 2003, p.86). The segment that I found particularly significant was the ‘space’ that Dalhberg, Moss and Pence (2013) referred to. The ‘space’ that is located between different forms of knowledge, in which they meet, interact and mutate into something new, something that is significant to those who ventured into that ‘space’:

What appealed was not the knowledge of the way forward (…), but the absence of knowledge and the opportunity it provided to explore together a way forward, to merge the different experiences and different bases of knowledge of our respective communities and see what could be generated out of a new dynamic, a new combination of ideas (p.180)

This reminds me of a discussion my coworkers and I had during our last pro-d day. One of the staff teams struggled to complete documentation, in terms of time and inspiration. They also struggled to engage with families and community members. The documentation that they had completed was magnificent. It filled up the boards, it was visually appealing and clearly reported the learning that had occurred in their program. However, ‘Space’ was something that was suggested, in terms of physical space on the boards, so that others could contribute, as well as in terms of inquiry. Their beautiful finished product did not leave ‘space’ for curiosity or alternative stories. Through our discourse, we generated multiple ideas as to how we could provide that ‘space.’ I can’t wait to see what they come up with.

The two-way dialogue developing the Generative Curriculum Model is similar to the Te Whāriki, being grounded in jointly designed principles, however different in that the former, as a University diploma program contained a curriculum that would enable trainees to “walk in both worlds” (Hodgins, week 6, 2018). According to Hodgins, (week 6, 2018) “… the curriculum is not designed to represent or foster the transmission of any particular “school of thought” or tradition, but rather to engage the teachers, learners, and the wider community in a journey of knowledge creation, the outcome of which cannot be known in advance” (pp. 8-9).

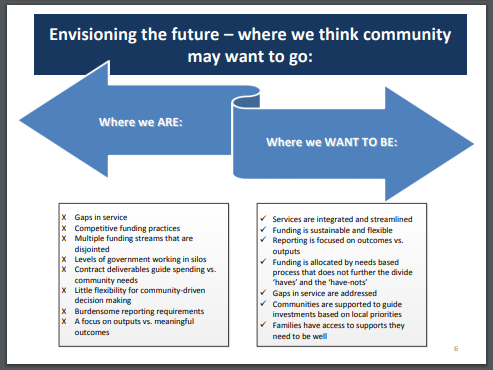

Corrine Sagmeister’s depiction of an Indigenous community approach to service provision that is not output-oriented but meaningful-outcome oriented mirrors the strength of the Generative Curriculum Model

She looks at the present and into the future, thinking about how Indigenous and other communities work together.

The dialogic approach to quality childcare is instrumental in halting the proliferation of developmentally appropriate practice (DAP) in the Majority world or Euro-western settings. DAP has been strongly empowered through modernism and wields “… potential for Euro-western assumptions and practices to disrupt, and potentially destroy, the fabric of family and community life…” (Hodgins, D. personal communication, 2018).

Dialogic approaches also expand potential to explore and better understand unfamiliar child-rearing values and practices. In the Canadian Euro-western setting this approach represents a fundamental step toward disentangling the grip of colonialism, and may move forward in enacting Calls to Action from the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, 2015). Taylor (2017), from the viewpoint of a non Indigenous early years trainee focussed on enacting call #12 reminds us that “In accepting that our knowledge is partial, we employ a pedagogy of listening” (p. 52). Te One (2003) concludes that the Te Whāriki has gained wide acceptance throughout the early childhood sector, reflecting the idea that curricula need to be culturally and nationally appropriate and this document has become the model for other countries designing their own early childhood frameworks, highlighting the benefits of two-way dialogue between Majority and Minority World in the promotion of community capacity building.

Impact of Assimilative Policies on Community Capacity Building

”In forcing assimilation and acculturation to Eurocentric knowledge, modern governments and educational systems have displaced Indigenous knowledge … Indigenous knowledge is now seen as an educational remedy that will empower Aboriginal students if applications of their Indigenous knowledge, heritage, and languages are integrated into the Canadian educational system.”

(Battiste, 2013, p. 87)

A colleague reflects Battiste’s position posting on implicit racism, one of the most pervasive impacts of assimilative policy on community capacity building for Indigenous communities.

Striving for Inclusion in Combatting Implicit Racism

Sunday, 25 March 2018, 4:08 PM

The readings this week acknowledge the prevalence of implicit racism towards Indigenous peoples, even when it is believed that there are efforts being made to respect and celebrate their culture. Absolon (2016) notes, “in any action of inclusion one needs to know intelligently that other peoples’ knowledge is valid and deserving of space” (p. 54). As Sandrina de Finney noted in our Week 9 class discussion, although schools commonly incorporate Aboriginal culture into their units or curriculum, they often do so in superficial ways. These lessons rarely demonstrate the past and current impacts of colonization upon Indigenous cultures. The educational system continues to colonize by misrepresenting people, culture, and connections to land and animals. Additionally, it is the colonized who are both blamed for their societal and educational shortcomings and viewed as responsible for resolving them. In my opinion, this is the ultimate exclusion.

Sandrina de Finney’s remarks:

Gebhard (2017) explains that racism continues to exist, and introducing Indigenous cultural studies while engaging in silence about racism perpetuates assimilative practices. It is only when appreciation for “… heritage, language and self-identification of the other are as significant, diverse and fluid as one’s own’ (Schick 2009, 122), then teaching and learning about Indigenous culture can be one component of unlearning racism and building settler-Indigenous alliances” (Gebhard, 2017, p. 14). She does caution not to be deterred from integrating Indigenous knowledge into curriculum, but to understand these practices are not mutually exclusive from anti-racism interventions and both belong in curriculum.

Absolon (2016) advocates for inclusion according to a wholistic framework drawn from the Four Directions of the Medicine Wheel and Seven Sacred Teachings (Benton-Benai, 1988; Nabigon, 2006).

Absolon (2016)

This wholistic framework is comprised of four interconnected and interrelated directions. A wholistic perspective, approach and application will socially include Indigenous people. According to Absolon, all directions are interdependent and interconnected to create a whole with each being attended and balance achieved through mindfulness in all directions. This will create a wholistic and ethical approach.

Sandrina de Finney asserts “At the heart of all my work is that rather than trying to Indigenize western research is to bring these knowledges back to the centre as our form of evidence.” She explains that Indigenous peoples have always had their own political systems, knowledge systems, child rearing, and ways of being. They have had them for thousands of years and they are currently muted, they have not gone away.

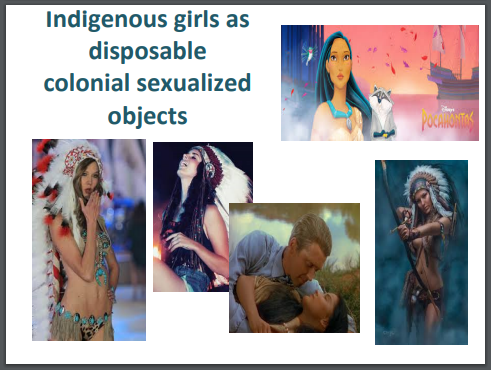

Ms de Finney presented the following slides. She clearly describes the impact of colonialism on Indigenous people in Canada:

Sandrina’s clarity on the impact of assimilative policy in Canada shed new light on the often misunderstood challenges Indigenous people face at the time of elections. To hear a story from the CBC series 8th Fire, please go to:

Why Vote?

(CBC 8TH Fire)

Ms de Finney describes a project with young Indigenous girls and the environmental impacts influencing the creation of this collage:

Ms de Finney speaks on gender-based violence against Indigenous women and girls in Canada:

Freedom Smith Myran simply and clearly describes her current reality as an Indigenous secondary school student. To hear her story, follow this video link:

Student opens up about crime, poverty and other challenges in North End schools

(CBC News Manitoba, Posted: Mar 23, 2018)

A modernist belief in “objective” knowledge combined with eurocentric and positivist logical perspectives regards measurement as the best way to hold this knowledge (Hodgins, personal communication, week 2, 2018). Hodgins (2018) explains a drive to “understand children” perpetually revolves around categorizing and assessing different facets of development, resulting in a large number of instruments to measure physical, social, emotional, and cognitive development, along with assessment of the environment’s ability to support development. Believing in the image of a “universal child” these measurements are used to ascertain if children from “disadvantaged” backgrounds are developing according to these measures, and because the measures do not acknowledge the realities of these children they do not perform well (Hodgins, personal communication, week 2, 2018). Hodgins (2018) concludes that the opportunity to build a deeper awareness of children according to our own cultural understanding, and the diversity inherent in understandings, social processes, and related capacities of children around the world.

Since these measures were not designed with the particular realities of these children in mind, it is not surprising that they often perform poorly. Lost in this circular, self-perpetuating logic is the opportunity to develop a deeper awareness of our own cultural understanding of children and of the diverse understandings, social processes, and related capacities of children around the world.

Ms de Finney clearly expresses the impact of assimilative policies on community capacity building:

While the impact of the Residential School System on Indigenous people in Canada is slowly becoming better known through the TRC, the two following CBC reports describe a system that continues to remove Indigenous children from their homes:

Hidden Colonial Legacy: 60’s Scoop

(CBC 8TH Fire)

Ottawa announces $800M settlement with Indigenous survivors of Sixties Scoop

(CBC News, Posted: Oct 05, 2017)

Community capacity building in the early years is a multi-layered and multidimensional model of care, advocacy, activism, education and social justice. It is in practice that one gains insight and knowing through self and group-reflective, team oriented work. Corine Sagmeister shares her experience of taking the work to one of its broadest levels in an Indigenous context. Her visioning experiences of Paddling Together and supporting community capacity at many levels evokes clear images of early years settings as the focal point to inspiring change:

References

Battiste, M. A. (2013). Decolonizing education: Nourishing the learning spirit. Saskatoon, SK, Canada: Purich

Publishing Limited.

Dahlberg, G., Moss, P., & Pence, A. (2013). Beyond quality in early childhood education and care: Languages of

evaluation (3rd ed.). New York, NY: Routledge.

Edwards, S., Blaise, M., & Hammer, M. (2009). Beyond developmentalism? Early childhood teachers’

understanding of multiage grouping in early childhood education and care. Australasian Journal of Early

Childhood, 34 (4), 55-63.

Hope, K. (2017). ‘The presence of a light table does not grant the possibility’ [Web log article]. Retrieved from

http://thespoke.earlychildhoodaustralia.org.au/presence-light-table- not-grant-possibility/

Kretzmann, J. P., McKnight, J., 1931, & Northwestern University (Evanston, Ill.). Institute for Policy Research.

(1993). Introduction, Building communities from the inside out: A path toward finding and mobilizing a

community’s assets. Evanston, Ill; (pp. 1-11). Chicago, IL: Asset-Based Community Development Institute,

Institute for Policy Research, Northwestern University.

McKnight, J. (1995). John Deere and the bereavement counselor. In J. McKnight, The careless society: Community

and its counterfeits (pp. 3- 15). New York, NY: BasicBooks.

McNally, S.A., & Slutsky, R. (2016). Key elements of the Reggio Emilia approach. Early Child Development and Care, 187(12), 1925-13.

Rinaldi, C. (2001). Reggio Emilia: The image of the child and the child’s environment as a fundamental principle. In

L. Gandini & C.P. Edwards (Eds.), Bambini: The Italian approach to infant/toddler care (pp. 49- 54). New York:

Teachers College Press.

Taylor, B. (2017). What do the calls to action mean for early childhood education? Journal of Childhood Studies, 42

(1), 48-53.

Te One, S. (2003). The context for Te Whāriki: Contemporary issues of influence. How the Maori curriculum

established through kohanga reo informed Te Whariki the national early years program, p. 32-33.

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (2015). Retrieved from:

http://www.trc.ca/websites/trcinstitution/File/2015/Findings/Calls_to_Action English2.pdf.

Varga. D. (2011). Look – normal: The colonized child of developmental science. History of Psychology, 14 (2),

137-157.