Great to be here.

Retired.

On vacation.

For the rest of my life.

Great to be here.

Retired.

On vacation.

For the rest of my life.

This is a big deal! I get to present my thoughts about Krishnamurti’s approach to the art of living and dying with “choiceless awareness.”

Should be great fun and stimulating too. My adventure, that is. Not the presentation. Talking about what Krishnamurti had to say is not really as interesting as living it.

Between two worlds

Awake and alone after the storm; droplets fall from leaf-loaded eaves

whistling wind uproots a buried regret;far away

Findhorn Experience Week; departure

she a white sea-campion; so close …

for a moment; her gentle hand clutching mine

decades separate us; could she possibly want me?

I turn to pull away; her hand squeezes mine

fingertips holding on; then slipping

outstretched; then gone

droplets fall from leaf-loaded eaves

awake and alone after the storm.

The flower has swallowed the goat.

The Marriage of Fiction and Nonfiction

In the beginning

And the Lord said to the man, “from all the trees in the garden you are allowed to eat. But from the tree of the knowledge of good and evil you are not allowed to eat. For as soon as you eat from it, you will die.”

Stories from the beginning of time feature some of the best lies.

After I’d read Bruce Chatwin’s The Songlines for a travel writing class, our instructor revealed that most of it had been made up. This revelation irked me at first, like my mother telling me late in her life she’d always thought the man I knew all along as my father was not my biological father. Chatwin’s narrator speaks in the first person, goes by the name Bruce, and there’s nothing in the text to suggest any of it had been concocted by the author’s prodigious imagination.

I’d been pranked.

The Songlines is a collection of philosophical and anthropological meanderings quilted together into a story by encounters with Aboriginals in Central Australia. Bruce explores human migration in parallel with his search for the etiology of his own restlessness. Early on, researching animal migration in the British Museum library in London, he comes upon “the most spectacular of bird migrations: the flight of the Arctic tern, a bird which nests in the tundra; winters in Antarctic waters, and then flies back to the north.” Later, as he steps out into the street he’s miffed to see a tramp begging for money being rebuffed by a well-heeled gentleman. He buys the tramp lunch. Over two generous helpings of steak, the tramp tells Bruce his life story, and then as they part, the tramp says: “It’s like the tides was pulling you along the highway. I’m like the Arctic tern, guv’nor. That’s a bird. A beautiful white bird what flies from the North Pole to the South Pole and back again.”

Chatwin’s magical nomadic metaphor, accentuated as it is by synchronicity, had sparked a visceral connection for me with Bruce and I’d felt comforted by the feeling there were many other nomads, migrants, and restless souls.

According to Keith Oatley, a Canadian scholar of the psychology of fiction, fiction means “something made, even something made up.” Compared to nonfiction, what he calls “things found,” Oatley notes people tend to be skeptical about fiction, a suspicion that “leaks into common usage: Fiction has come to mean falsehood.”

In the middle

And the serpent said, “You will not die. God knows that as soon as you eat from it, your eyes will be opened, and you will be like gods, knowing good and evil.” And when the woman saw that the tree was good to eat from and beautiful to look at, she took one of its fruits and ate, and gave it to her husband, and he ate too. And the eyes of them both were opened, and they knew that they were naked.

The first frame of the three-part made-for-television movie “The Widower” displays these words on the screen:

This is a true story. Some scenes and characters have been created for dramatic purposes.

In Tell It Slant, Brenda Miller and Suzanne Paola suggest the essayist makes a “pact with the reader” to tell a “true story, one rooted in the world as we know it,” as if the writer had taken a solemn oath to tell the truth, nothing but the truth, and the whole truth. This unmentioned pact means the writer won’t deceive the reader into believing something that turns out to be false.

Miller and Paola concede there is no easy answer to the question of how much a writer can invent or embellish. Writers differ in worldviews and attitudes about questions of ethics and truth, and about the extent to which they acknowledge a truth pact with the reader. Some creative nonfiction writers believe nothing should ever be knowingly made up; others aspire to create an engaging written work, fabricating details and composite characters, and reconstructing events, all with an eye to telling a more engaging story.

I’ve narrowed my philosophy of life to one three-word rule: “Do no harm.” This comes to me from the Hindu/Buddhist notion of ahimsa, not from the physician’s Hippocratic Oath. So I’d say Miller and Paola’s stance seems an appropriately ethical approach.

While I admire Keith Oatley’s definition – that fiction is made up – I’d say that nonfiction is mostly reality, actual, and accurate, while fiction is mostly made up or imagined. But Oatley makes the provocative proposition that fiction may be twice as true as fact. Fiction, he says, dives into deeper truths – matters that nonfiction often doesn’t bother with. And if what Oatley says is true, then why should we abide any notion of a truth-pact?

The way I read it, the truth is that fiction is almost always made up but set in a context of real life. It’s almost always partly true and factual. Likewise, most creative nonfiction is almost always set in a context of real life, but is also almost always partly invented, imagined. Every story, whether labeled as fiction or nonfiction suggests some kind of truth, because every story is constructed in the mind of a fallible human being possessed of an imagination.

Creative nonfiction leads with the adjective “creative” because creative nonfiction aspires to be Art – in other words – literature. In that striving to achieve artistic worth, creative nonfiction writers evoke and provoke emotional responses and meaningful insights in readers. Good writers aim for the lofty heights of art, but also to engage readers using the hypnotic power of narrative. And as the creative nonfiction writer aspires to create art by writing literature and story rather than reportage, it’s tempting to prefer dramatic effect and affect over factual accuracy. (What Farley Mowat advised: “Don’t let the facts stand in the way of a good story.”)

Bruce Chatwin’s The Songlines is a literary work of art. I know several people who place it high on their list of favourite books. But not one has griped after I’ve mentioned casually that most of it was made up. Chatwin understood, I think, long before psychologists began to study reader response in fiction and nonfiction, long before Keith Oatley proposed that fiction may be twice as true as fact, that readers want – no, that readers are owed – a good story told well more than they desire facts.

David Gessner, in his “Everything You Ever Wanted to Know About Truth in Nonfiction But Were Afraid to Ask: A Bad Advice Cartoon Essay,” proposes creative nonfiction is writing that shares many techniques used by writers of fiction such as scene, dialogue, and setting. He reminds us that De Montaigne flatly admitted his essays were a product of a feeble memory; Thoreau squeezed two years into one in Walden Pond; Orwell created whole scenes. And in much of creative nonfiction today, several characters are often conflated into one, and rare is the writer who does not “re-create” remembered dialogue.

What is the real harm here? Since we live in what Gessner calls “a culture that values money and fame and emotional meaning in published writing,” should we be surprised that writers “stretch the truth?” Haven’t humans since the beginning of time been telling tall tales to impress the tribe? Or maybe it all started when men first came back from hunting and fishing with their stories of great feats of survival and subsistence. (Or maybe it’s a masculine flaw?) The bear was seven feet tall and had paws the size of a tennis racket; that trout weighed twenty pounds and fought me off for an hour, and so on. Aren’t humans the storytelling animal?

Gessner suggests pre-empting reader expectations and potential harm by cueing the reader with a cautionary note in appropriate places (like the note that opens the film “The Widower”). Ernest Hemingway’s memoir of his five years in Paris in the 1920s opens with a preface that offers: “If the reader prefers, this book may be regarded as fiction. But there is always the chance that such a book of fiction may throw some light on what has been written as fact.” And Ruth Reichl, one of a rapidly growing cadre of flexible creative nonfiction writers, proclaims everything in her book Tender at the Bone: Growing Up at the Table “is true but may not be entirely factual,” having learned early on the most important thing in life is a good story.

Certainly life is a story. But Gessner warns “a misplaced fact here and there can be forgiven, but an overall lack of honesty will not.” He calls on creative nonfiction writers to dig for the truth, “examine it, play with it, rest on it. It’s the best thing about writing. (And that’s a fact.)”

I’m not obsessed with truth. Not factual truth. Meaning is so much more stimulating. Or maybe I’m just not comfortable with the truth. On those rare occasions when the four Flexer siblings get together (I’m the oldest), we often slide casually into recounting stories from our common past, stories that inevitably have one of our deceased parents as protagonist. For instance, a few years ago we’re all in Toronto at my brother’s house for a couple of days. After the dishes are put away, I casually ask my brother why, at the age of fourteen, he’d been sent off to England for a year.

My brother pauses to think. “She couldn’t feed all of us. And you were going off to the army. It was a good deal for her because Yona and Peter offered to look after me like their own.”

“NO,” my sister – the memory-keeper – smiles knowingly and turns to my brother: “She wanted you to learn English and get a first-class education. We all knew you were bored with school and she wanted to let you live in a different world.”

I want to say I’d always thought my mother had grown tired of her four unruly and ungrateful teenagers that she’d worked so hard to bring up; maybe she’d finally had enough. I’m not so sure anymore. And it’s too late to ask.

Apparently, from the time we can speak, grown-ups inculcate us into the cult of “Truth.” But according to Dr. Frances Stott, child development scholar, learning to fib is an important step in every child’s development. And grown-ups tell lies of convenience frequently, while children watch and learn.

What’s more, psychologist Dr. Bella DePaulo finds lying is a condition of life. In a 1996 study, DePaulo and her colleagues asked 147 people between the ages of 18 and 71 to record all the lies they told in one week. Most of them admitted to lying once or twice a day, and in a week, on average, they lied to 30 percent of people they’d interacted with. Worse yet, Dr. DePaulo concludes, some types of relationships, such as between parents and teens, are often built on foundations of deception.

Everyone lies; some people more than others.

Jonathan Gottschall, author of the book The Storytelling Animal: How Stories Make us Human, wasn’t surprised that John D’Agata, who teaches creative writing, defends rampant inaccuracies in his magazine articles by glibly asserting he’s an artist, not a reporter. Sometimes artists have to lie to get to the truth. For Gottschall, D’Agata’s response is wholly consistent with how we tell our own stories. “We all spend our lives crafting a story that makes us the noble-if flawed-protagonist of a first-person drama.” Seems our life stories, like D’Agata’s essays, are only based on true stories.

Reading The Songlines I found myself transported into the story of Bruce’s journey through scenes and dialogue and action, punctuated by Bruce’s reflections and anecdotes. Chatwin had written a literary novel. Had I known at the time most of it was fiction, I don’t think I would have been transported any the less. Chatwin could have used Hemingway’s opening, “this book may be regarded as fiction, but there is always a chance it may throw some light on what has been regarded as fact.” But it would have been superfluous.

In the end

And Cain said to his brother Abel, “Let’s go for a walk.” And when they were alone, Cain turned on his brother Abel and killed him.

And the Lord said to Cain, “where is your brother Abel?”

And he said, “I don’t know. Am I my brother’s keeper?”

When it comes to creating engaging and meaningful stories, scenes and conversations are better reconstructed rather than described in factual language (although at times this may be what the story calls for). Getting at the deeper truth, making art and literature, telling dramatic stories, all these invite techniques of fiction.

Creative nonfiction is nonfiction fictionalized. Facts are malleable. Truth is in the eye of the beholder. Engaging narrative weaves together reality with imagination to ignite a spark of human community; to invoke and incite meaning; to invigorate emotion. So what do we mean by “creative”? Creativity is the application of imagination. And what is imagination? Imagination comes from what is not real. Creativity flows from imagination and is imbued with the unreal. And that’s one of the elements of The Songlines I’d appreciated most – Chatwin’s imagination articulated on the page.

I’d say much of the best nonfiction is at least partly fiction. Just as the best fiction is at least partly fact. It’s an interesting paradox, a paradox that holds true for metaphor as well. As Canadian poet and essayist Don McKay once said: “Paradox is central to metaphor; a metaphor must be false to be true.” A meaningful metaphor transports the reader to something different from the subject of comparison. The aim is to illuminate meaning by shifting mental context. The same might be said of creative nonfiction; creative nonfiction is fact (and truth, and reality) illuminated by fiction. Just like fiction is a dream clothed in reality.

In November, 2007 the Associated Press reported on a legal settlement for readers who asked to be reimbursed after buying James Frey’s best-selling memoir, A Million Little Pieces. Frey had earlier acknowledged that he’d made up significant parts of the book. The settlement offered a refund for anyone who’d bought the book before Frey confessed. But strangely enough, even though sales exploded after Oprah Winfrey chose it for her book club, only 1,700 readers wanted their money back.

As part of the settlement, Random House agreed to put a warning in future editions that some parts of the book were not quite accurate. Still, over 90,000 copies of the book were sold in just seven months after the controversy erupted. A Million Little Pieces stayed on the best-seller list for another six months. Frey earned over four million dollars in royalties before the court settlement in 2007.

New York Times columnist Andrew Harvey, in his 1987 review of Bruce Chatwin’s The Songlines, called it a book that combines fiction and non-fiction, a blend of “Chatwin’s reflections with a made-up story taken from two trips he’d made to Australia.” In an interview, Chatwin admitted his Australian tales were based on ”incoherent scribblings” about real events, later reshaped by his writer’s mind. ”To call it fiction isn’t strictly true, but to call it nonfiction is an absolute lie,” he said.

Chatwin was surely on to something. D’Agata and Reichl, and hundreds like them, will, I imagine, continue to play with factual truths while digging for deeper truths. They’ll give us better stories. They’ll create literature and art. The marriage of fiction and nonfiction gave us creative nonfiction, a kind of Cain blended with Abel. The first strives for stability and tradition and is content in one “ethical” place, while the second tends to roam and seek out new territory. Will one try to destroy the other, or will both learn to appreciate the nature of their origin and paradoxical relationship?

Vancouver General Hospital. 4:00 a.m. She has not had much sleep in the past thirty hours, but Shelley Cairo is wide awake. She lifts herself out of bed. Checks on her baby in the incubator. Goes for a stretch. Out in the hall and around the corner, there is an unattended nursing station. A clipboard hangs from the edge of the counter. Her gaze fixes on four words, about halfway down an otherwise white sheet – ‘Baby Cairo DOWN SYNDROME?’

“I felt on fire. Like being told my baby was retarded. Or that he was going to be a vegetable for the rest of his life. I was angry at God”.

Wavy brown hair flows casually to her shoulders. Her blue-grey eyes and gentle smile tell you this woman does not easily lose her cool. Growing up in Kamloops, Shelley was a tomboy. She rode horses. She was shy and quiet. She was in awe of the wave of unwashed youth that hitch-hiked through the Okanagan in the late 60’s.

But what Shelley wanted more than anything was to be a mother. Shelley was 18 when she married Chris, when the twins Tara and Jasmine were born.

Shelley and Chris were rebels. Drop-outs. Idealists. “We were deep into yoga, meditation, spirituality,” she says with a wistful smile. They had tried back-to-the land country living, but had given up after a few years and moved to the big city.

Back in 1981, home births were almost unheard of. For Shelley, nothing could have been more natural. Shelley remembers thinking the baby looked unusual. Slanted eyes – Asian. But she thought ‘Felicity has eyes like that too. And look at the toes. But so and so has toes like that’. Baby looked clunky, like he’d been chopped with an axe instead of cut out with scissors. Beautiful – but the curves of his body seemed square. “My mind was making all these observations but I also saw the truth – maybe he was different, but he was perfectly fine.”

One of the midwives noticed the yellowish skin, suspected jaundice, and called the doctor. The doctor took one quick look at the baby and frowned. “Best to take baby to the hospital.”

At VGH, the paediatrician showed Shelley – pointing with a pencil – the Down Syndrome markers on baby’s little body. Shorter body proportions. Flattened nose. Smallish mouth. Squarish face. Short stubby fingers. Straight black hair. And a single transverse crease in each palm.

A geneticist told her they would never be able to leave the boy on his own – ever. DS people can have learning disabilities, congenital heart disease, and are at high risk for a whole range of health problems.

Shelley gently lifts her baby out of the incubator and holds him tight to her chest. “I was there with my son, and with God. And I looked into my baby’s eyes and I could tell he wasn’t worried about any of that. He wanted to live. To eat, and breathe, and move around. And I made a vow. Between this God I was mad at, and my son – no matter what any doctor said – I was going to see the best, and do the best for my son.”

They named him Jai. (Rhymes with ‘my’ and ‘guy’). Victory in Sanskrit. Jai would overcome the limitations of his diagnosis. Down was not going to keep this boy down.

Shelley recalls Chris wouldn’t talk about Jai having DS. He just didn’t believe it. One day, they were listening to the radio when Jai’s Infant Development Program worker was giving an interview. She was talking about Shelley taking Jai for a walk in the forest, showing him how to pick berries. And how that developed his grasp, and made his stubby little fingers stronger. That’s when Chris turned to Jai with a proud father’s grin. “So – you’re one of those famous Down kids!”

In the first year, the Infant Development Program worker came to the house a few times a month to show them how to play with Jai. One of the games they played was the Copy-Cat game. Tara and Jasmine would copy Jai’s movements. Then he’d see what they were doing and imitate Tara and Jasmine. Or Jai would follow a crayon with his eyes as Tara floated it through the air. Another game was the Hide-Away game. Jasmine or Tara would surreptitiously hide a piece of Lego or some other toy and Jai would scramble, find it, and clasp it in his hand.

When Jai was three he went to a preschool at UBC. When the woman in charge said kids like Jai need to be with their own kind, Shelley moved Jai to a preschool closer to home. That didn’t turn out so well either. Then Shelley found a day care run by a woman who said she liked to work with special needs kids. But once she saw how much attention Jai was giving the house rat, she abruptly lost interest.

One spring day when Jai was four, Tara announced that she wanted to make a TV commercial to tell the world her baby brother was OK. Shelley thought about maybe creating an educational video for parents with DS babies. Too ambitious. But when Shelley’s friend Irene shot a bunch of cool pictures of the whole family just being with Jai, Shelley had another idea. She sat down with the girls and they looked at the pictures. And together they jotted down what they wanted to say about their brother Jai. They chose the best pictures to match their words, and created the children’s book Our Brother Has Down’s Syndrome. The book was published by Annick press in 1985. It’s still in print.

Shelley accepted the challenge of raising Jai as her life’s mission, and she was fascinated by the child development aspects. “I’ve had to fight many dragons – both internally and externally.” She had got in the habit of being cloistered at home. Going out had been a challenge. “Then I had this kid who was so different. I knew Jai had to be exposed to the world, and I had to overcome my reclusiveness for his sake.”

When Jai was in grade two, Shelley heard from a friend that one of his special ed teachers hated ‘those DS kids – they’re so touchy-feely.’ When Shelley came by to get Jai one afternoon, he burst into tears the minute he saw her. That teacher had punished Jai for spitting, by demanding he write out 150 lines of ‘I will not spit’. Shelley took the lined paper from Jai’s hand, tore it up into shreds and threw them at the teacher’s feet. “If you want Jai to like writing, why would you choose to punish him this way?”

Shelley and Chris have since separated. Chris has another family now. Still, he is a big part of Jai’s life. He’s his hero and champion. Shelley took a part-time job at Banyen Books. And she became a volunteer advocate for special needs kids.

Shelley found Jai a high school that integrated special kids into regular classes. He got an A in Art. His innate curiosity came alive in science class. And he wrote stories. He would tell his story to a teacher’s aide, who would type it up, then Jai would print it out in his own handwriting. One of his stories was about a horse named Quill who caused havoc in the streets of Vancouver. It was published in the community paper. Shelley has a collection of Jai’s old stories – over 30 of them.

Jai tried hard to fit in. After seeing the other kids smoking outside, he pretended to smoke too. But he never stopped being Jai. He got around by riding his imaginary horse. And he talked to his imaginary friend, George. Too much George could be a problem at school, so Shelley asked Jai to spit George out into a jar as he left for school each day. George lived in his mouth.

Shelley is a grandmother, an elder. They recently celebrated Tara’s wedding. Jai looked sharp in his black suit and tie. He lives in a house that’s not exactly a group home. Most days he makes his own breakfast. He does his own laundry. But sometimes his dirty clothes don’t get further than the laundry basket.

Friday night dinner with Jai is the highlight of Shelley’s week.

“He cares about people. If someone is talking about their troubles, he says ‘life is complicated’.” You hear more than motherly pride when Shelley talks about her son. “He has great compassion for disabled people. He says ‘Oh, that poor guy’. And he’s always telling me I should take it easy.”

Shelley’s philosophy used to be that good things come to good people. “And now I see that it just is. People and animals are born all sorts of ways. It’s up to each one of us to see the special as a tragedy or a gift.”

Rainbow Valley Ecovillage, New Zealand, November 1999

It sounded like a gunshot! From inside the house. From the room just outside my bedroom door. I opened the door slowly and peered into the living room. There was Udaya, kneeling on the couch, holding a shotgun pointing out through the open window.

“What are you shooting at?”

“Possums. They climb into the trees when it gets dark and eat my fruit.”

“Did you hit any?”

“No, but I think I scared them off.”

“You going to do any more shooting tonight?”

“No, that should keep them away for now.”

“OK. I’m going back to sleep.”

Late the next morning, I asked Udaya to show me how to get to the giant kauri tree. He took me to the end of the valley on the back of his quad bike. He warned me that the trail had not been maintained for some time, and guessed it would take me about two hours to get to the tree. I set out with my day pack on my back, two liters of water and food inside. It was a warm spring day, sunny, and dry. I walked along the trail at an easy pace for some time. Then there was no trail any more. Just then I spotted the thickening of dry vine forest that Udaya mentioned would signal the spot where I needed to take a sharp right. I could tell I was near the edge of the plateau; there was more sunlight seeping in from above, and a soft breeze picked up ahead of me.

And then there it was. On the very edge of the plateau it stood, a true elder, spared only by its location. There would have been no way to cut it down, and no way to salvage it. It was hugging the 150-meter high cliff. One side of its two- and-a-half-meter diameter base was on level land on the plateau, the other side out in thin air. I couldn’t tell how tall it was, but I could believe it had been alive 1200 years, as Udaya said. I stood there in awe. This was not a tree you could hug. All I could hear was the wind. Sitting down, with my back to the tree, I drank water and devoured my sandwich and apple.

The Coromandel Peninsula was covered in kauri forest when the European colonizers first arrived. One of the largest kauri is the Father of the Forests in Mercury Bay, with a reported girth of twenty meters. Fire destroyed the Father of the Forests. Such is the fate of many fine trees in New Zealand, many fires intentionally set. Most of the kauri forests of the Coromandel were logged and burnt, but fortunately they have been regenerating, and some kauri stands were left untouched.

Udaya had once been a prominent member of the Friends of the Western Buddhist Order. He left Auckland to establish an ecovillage in this natural 800-acre subtropical paradise. And there he was shooting at possum. Not a very Buddhist thing to do, I suppose. Not that I was surprised by his animosity towards these fruit-loving forest marsupials. Staying at a hostel once, I met a local man who made his living trapping and selling dead possum to the possum fur industry. And hitchhiking to Thames one day, I had a ride with a Maori man who made his living advising the Department of Conservation on the best methods of trapping possum. In New Zealand, the possum is a pest. Still, even now, the memory of Udaya blasting the possums from his living room couch is a vivid image of the absurd.

So there I was, far away from civilization, alone with my new friend. Kauri had been logged here for over a thousand years, and this loner was still very much alive. I stretched out on the ground next to the trunk, closed my eyes and took a deep breath of fresh forest air. I must have dozed off for an hour, or two – I couldn’t tell. Waking up to reality, I peered through the branches to see the sun in the sky. My guess was two hours of daylight left. Collecting my pack, I started hurriedly walking back the way I came. Within a few minutes, though, it was clear to me that I had no idea how to connect with the trail. The look of the dense vine forest, with its giant trees and ferns, is so different coming from the opposite direction; and of course, there is much less light when the sun is low in the sky.

I was lost. And I panicked. Thoughts came quickly. If I could not get out of the forest before sunset, I would have to spend the night here. I wondered if Udaya would come looking for me. Would I be safe in the forest at night? Then I stopped thinking. Sitting down on a mossy, fallen tree, I took a swig of water. And then, slowly, my equilibrium returned. I looked over in the direction I expected to see the beginning of a trail, thinking maybe I could spot a landmark, recognize a broken branch, or vines wrapped around a familiar tree. Astonishingly, almost right away, looking out in front of me about five meters away, there was a clump of forest I had seen before. It looked like the spot where I turned to the right, heading for the kauri. I got up and took a few steps. Then I was sure of it. What a relief! There was the trail straight ahead.

By the time Udaya’s house appeared up ahead, the sun had set and it was almost dark. A feeling both eerie and comforting came over me. Had there been some mysterious energy, some power or force, out in the forest, guiding me to the trail when I was lost?

Tararu Valley, New Zealand, December 1999

I met Sarah, from Victoria, at the Tararu Valley Sanctuary and Land Trust. Just eighteen, curious, full of life, and intelligent, Sarah was taking a year off school to be an environment volunteer. Her job was to look after the stoat traps. Stoats are slender-bodied carnivores, part of the mustelids – the weasel family. They were introduced to New Zealand in the late 19th century to control the rabbit population, itself introduced to New Zealand earlier that century. Rabbits were brought for sportsmen to hunt, for food, and to remind the British colonizers of home.

Stoats eat the kiwi bird eggs and kill the kiwi chicks. Only five percent of kiwi birds that hatch survive, and half the kiwi population is lost each decade. I am not sure why the New Zealanders work so hard to prefer the kiwi over the stoats, but there must be good reasons for this, other than the fact New Zealanders are known around the world as kiwis.

Sarah walked the trails each day, checking the traps. Most days she would take a few golf balls with her. As far as a stoat was concerned, a golf ball was a kiwi egg. Sarah would make sure the trap was well situated to entice a stoat, and had a golf ball inside. There were dozens of these wooden boxes spread throughout the property’s winding trails. Sarah said the worst part of her job was removing the dead stoat, as the smell of a decomposing stoat was beyond tolerance. And she was not totally comfortable being involved in killing animals just out for an easy meal. But, she did say with some nonchalance, any time she would find a dead stoat in the trap, she would simply fling it as far as she could into the dense brush – that was the extent of stoat disposal.

I liked Sarah. One day, we were talking about philosophy and books. I mentioned my love of Zen and Taoism, and she said she was travelling with a copy of the Tao Te Ching, a gift from her mother. That impressed me! Now I liked her mother too. Sarah lent me her copy – the Vintage Books edition, translated by Gia-Fu Feng and Jane English. Here is a section I like:

Do you think you can take over the universe and improve it?

I don’t think it can be done.

In the pursuit of learning, every day something is acquired.

In the pursuit of the Tao, every day something is dropped.

Less and less is done

Until non-action is achieved.

When nothing is done, nothing is left undone.

The world is ruled by letting things take their course.

It cannot be ruled by interfering.

I stayed with the land trust for a month, and then moved two kilometers down the valley road to volunteer with the Buddhist retreat center. Sudarshanaloka, or Land of Beautiful Vision, was a sprawling property, its holding stretching from the river valley in the West, to the mountaintop clearing where the Stupa sat. Buildings on the property were the main house, a row of huts for residents and long-term visitors, a meditation hut, and five retreat cabins spread out in the forest. Members of the order would come from all over the world for silent solitary retreats, lasting anywhere from one month to as long as three years. The small resident community on the property looked after all the needs of the retreatants, delivering food and supplies every Friday.

In January, the river flooded, filling with water from the mountains after three days of non-stop heavy rainfall. The overflowing river made getting out of the center impossible, because the ford on the road was a meter below the water level, and the river ran much too fast and powerful. After waiting anxiously for two days, hoping the water level would drop, Pierrick and Buddhadasa hired a helicopter to airlift them into town so they could catch their flight to Australia for a conference.

That afternoon, while inside the house, I heard loud intermittent banging sounds that sounded like the Gods were playing billiards with boulders. It was still pouring rain. I grabbed an umbrella and walked gingerly down the muddy hill to the river to see for myself. The water was brown. It was carrying whole trees, large branches, boulders, and other debris down to the sea. I stood there stunned, umbrella in hand, sweatpants rolled up to the knee, in a T-shirt, and beach shoes on my feet, standing on a rock by the river. The sound of boulders colliding as they floated past me was something I had never heard before.

A few weeks later, the community decided the possum population on the property was becoming too much of a nuisance. Earlier one evening, we heard a loud “Hey!” from Punyasri in the library, and we went in to find a possum sitting inside the trash can, staring at us, an apple core in its mouth and the look of a child caught with a hand in the cookie jar. It must have crawled in through the open window. We turned out the light and Buddhadasa shood it back out the window. At the community meeting, after much discussion – they normally adhere to the ideal of ahimsa (non-harming) – the decision was taken to scatter anti-possum poison pellets.

About a week later, as I was rising one morning, I was accosted by a stench as awful as I had ever known. When I mentioned this to Guhyaratna, my neighbour, he said it must be a dead possum that had eaten the poison and died in the crawl space under our huts. “It’s going to be a big job finding it and getting it out of there”, he said unhappily, knowing full well it was going to be his job to do. I could not help but have a little silent private chuckle, observing this little war between the humans and these innocents of the forest.

A few days later, walking down for dinner one evening, I spotted Buddhadasa on a ladder, tying two big black plastic bags full of garbage to the joists just outside the rear entrance to the house. Seeing my puzzled expression, he explained: “Garbage pickup isn’t until Wednesday; need to keep this away from the possums.” ‘Good idea’, I thought.

The next morning, after my yoga in the meditation hut, I was eager for some breakfast. On my way into the house, I saw what normally would be good reason for expletives and frustration. But I could barely keep myself from laughing out loud. There was garbage strewn all over the floor. Still attached to the joists above were the torn remnants of two black plastic garbage bags, with packaging material and other waste peaking through big wide open holes. We cleaned it up in just a few minutes. Buddhadasa did not say a word. I thought of an ancient Chinese poem:

Sitting quietly,

Doing nothing

Spring comes.

And the grass grows by itself.

When I was four or five years old, growing up in Israel, I’d sit for hours pretending to read. I remember a photo, a white-bordered jagged-edged black and white, of a freckled round-faced boy, in a horizontal-striped T-shirt and shorts, sandaled feet, sitting in a wicker and metal chair peering casually into a large Hebrew edition of The Little Prince, with that golden-haired boy in his blue cape on the cover. I’m sure my little boy imagination marveled at the celestial travels and adventures of the boy prince. The mysterious rose, the fox who wanted to be tamed, the prince’s ascendance to the heavens after being bitten by the conniving snake, all this was too much for a little boy to comprehend. Much later, I’d rediscovered The Little Prince as an adult and I learned about the aviation adventures of Antoine de Ste. Exupéry, the explorer of place and life, who wrote he “always loved the desert. One sits down on a desert sand dune, sees nothing, hears nothing. Yet through the silence something throbs, and gleams.”

It’s still the first week of January and I’ve got great plans. I’ve been thinking about hearing. Hearing is a peculiar ability – it requires no effort whatsoever. The world is full of sounds of great significance and beauty, but who cranes their awareness to notice? I surround myself with sound and pretend to hear what people tell me and the news on TV and Glenn Gould’s Goldberg Variations emanating from the stereo speakers, but do I really hear or am I escaping the noise that constantly floods my consciousness? It is surely tragic for anyone to be within hearing of songbirds at low tide on a breezy afternoon when the sweet songs of finches and crows mingle with the whoosh of air in the leaves and the splashing of waves on mossy boulders, oblivious to the sacred succor of earthly sounds. But if you cultivate a healthy but simple awareness, so that the chirp of a sparrow or the lull of the surf will lighten your load and make your day, then, since the world throbs and gleams in melodious sounds, you have with your simplicity acquired an enduring equanimity. It is that simple. What you hear is the sound of life. Water, wind, life.

When I first discovered music, with my new-found post-pubescent consciousness, I’d listen (on vinyl) to Jimi Hendrix, on the floor supine, eyes shut, thoughts and worries drifting away into an ocean of nothingness. Guitar notes flow in waves from the left to right and then back again. Some say “1983… (A Merman I Should Turn to Be)” is a surreal apocalypse evoking Jimi’s despair of mankind, where he finally returns to the sea, the source of all life. For me, as a teenager, Jimi’s psychedelic sounds of waves and sand kept my mind off what was happening, but not by shutting life out altogether. Sometimes, I’d fall asleep to the undulating sounds of Electric Ladyland only to wake up to the scratchy sound of the needle on the non-grooved circle of vinyl closest to the centre-hole. Some of the lyrics have stayed with me to this day: So my love and me decide to take our last walk through the noise to the sea; Not to die but to be reborn, away from lands so battered and torn.

But music, they say, depends on silence to give brilliance to melodies and rhythms. Music scores come with notated rests for periods of silence, for contemplation and reflection – on the music and on life. The composer John Paynter once said that composers rely on silence for dramatic effect. In Bach’s St. Matthew Passion, the pause between “have lightnings and thunders …” and “open up the fiery bottomless pit O’ hell,” abandons us in solitary terror as we are flung brutally away from all we know and are left staring blankly into the infinite ineffable void.

In all spiritual traditions silence is a metaphor for inner stillness. But inner stillness is not about the absence of sound. Stillness connects us with the universe, ultimate reality, one’s own true self, or one’s divine nature. Silence transforms. Eckhart Tolle says that silence can be seen either as the absence of noise or as the space in which sound exists, just as inner stillness can be seen as the absence of thought, or the space in which thoughts are perceived.

Kristin Buehl, deaf from birth, receives a cochlear implant at the age of twenty-one. “My audiologist asked if I could hear her. After seeing me shake my head, she expressed surprise. Then it hit me. The undulating waves I was feeling in my head were actually sounds, not my imagination.” And after three decades of deafness, at the age of 47, Beverly Biderman turns on her new cochlear implant and takes a walk to a ravine beside the hospital. She says “it’s gorgeous on this beautiful summer day and voluptuous with sound. There are what seem to be thousands of birds, all very noisy, but the sounds together, are rather nice. I feel connected, a part of the scene. I see a group of little children from a day camp, strung together with rope. They are singing a song, and I can catch a rhythm to their singing, and it sounds high and sweet and fine.”

I think hearing is a gift too easily neglected. I hadn’t noticed the contrast between sound and silence and how much it connects me with my place among the living and all of nature in its undeniable beauty; beauty in the roar of a waterfall, the laughing call of a kookaburra, whispering winds and gushing waves, and the stillness of silence.

This exploration of Native American traditions proposes a diagnosis for the disconnect modern humans experience from nature and considers traditional Native practices as potential therapy people might take up to heal the rift. The Native American “way of being in the world” – what Luther Standing Bear calls “Indian mind” and Joseph Couture refers to as coming to “‘know’ as an Indian knows, to ‘see’ as an Indian sees”, is in my view, a kind of “nature consciousness,” an elemental component of Native American religions. Nature consciousness embraces the whole of the environment and nature, and everything in it, in one community of life.

For Native American author and religious scholar Vine Deloria Jr. “tribal religions have a natural affinity with living creatures in a fellowship of life.” The Hopi, for example, “revere not only the lands on which they live but the animals with which they have a particular relationship.” (88) The great disconnect, or alienation, of whites from nature, Deloria points out, has its fountainhead in the way Christians interpret the story in Genesis, with man reigning supreme over all other creatures. Indian tribes, on the other hand, view all living beings as sentient. Animals are “people” in the same way that human beings are people. Plains Indians considered the buffalo as a people, and Northwest Coast Indians regarded the salmon as a people. This “recognition of the creatureness of all creation,” an attitude that opens the door to relatedness with every part of creation, is what Indians have that Westerners lack. For some tribes this relatedness even extends to plants, rocks, and natural phenomena considered by Westerners inanimate. Deloria quotes Walking Buffalo, a Stoney Indian from Canada:

Did you know that trees talk? Well they do. They talk to each other, and they’ll talk to you if you listen…I have learned a lot from trees; sometimes about the weather, sometimes about animals, sometimes about the Great Spirit. (89)

One unfortunate symptom of the Western alienation from nature is the chasm between “wild” and “civilized,” a chasm that leaves the white mind fearful of wilderness. But in the Indian view of the world there was no fear of nature. Luther Standing Bear put it this way:

We did not think of the great open plains, the beautiful rolling hills, and winding streams with tangled growth as “wild.” Only to the white men was nature a “wilderness” and only to him was the land “infested” with “wild” animals and “savage” people. To us it was tame. Earth was bountiful and we were surrounded with the blessings of the Great Mystery.

One other aspect of the human-nature disconnect is Western obsession with scientific thinking that prejudices Indian religious beliefs as mere superstitions. In Deloria’s experience, Whites consider Indian dances for rain, for example, to be mere superstitions, and songs to make corn grow as absurd. But Deloria points out that white people believe they can make plants grow with music, suggesting perhaps that Indian tribal religious practices integrate certain truths only recently acknowledged by science. It seems imprudent to think it absurd or superstitious that one can learn to hear the trees talk. For Deloria, naturally, “it would be strange if they did not have the power to communicate.”

For N. Scott Momaday, a Native American author of Kiowa descent, the Indian “con-conceives” of himself in relation to the landscape. Momaday sees the Native American ethic with respect to the physical world as reciprocal appropriation, “appropriation in which man invests himself in the landscape, and at the same time incorporates the landscape into his own most fundamental experience.” Momaday’s “appropriation” is about moral imagination. As Momaday sees it, we are all, “at the most fundamental level what we imagine ourselves to be,” a conception that seems to sit well with the notion of nature consciousness. The Indian thinks of himself as a being in relationship with the physical world. He “imagines” himself in terms of that relationship, an attitude evolved over many generations as an integral aspect of cultural memory.

In the 1930s, Luther Standing Bear described this aspect of cultural memory when he wrote: “The Lakota was a true naturist — a lover of Nature.” Lakota loved the earth “and all things of the earth;” the soil was “soothing, strengthening, cleansing, and healing.” In contrast to Lakota nature consciousness, however, the white mind does not feel toward nature as does the Indian mind, a discrepancy Standing Bear attributes to child-rearing practices. Growing up, Standing Bear would see white boys gathered in the city street “jostling and pushing one another in a foolish manner…..aimless, their natural faculties neither seeing, hearing, nor feeling the varied life that surrounds them. There is about them no awareness, no acuteness.” In contrast, Indian boys were “naturally reared…alert to their surroundings; their senses not narrowed to observing only one another.”

In Standing Bear’s Lakota world animals had rights, and in recognition of these rights the Lakota never enslaved animals, and took life only to the extent needed for food and clothing. Indian nature consciousness precluded “antagonism toward his fellow creatures.” The Indian and the white man sense things differently “because the white man has put distance between himself and nature.” What Standing Bear learned from the elders is that “man’s heart, away from nature, becomes hard.” (197)

In 1985, Nuu-Chah-Nulth elder Mabel Sport wrote to the editor of the tribal newsletter about the local Bull Head Derby, a recreational fishing tournament common in the Pacific Northwest, held to encourage children to take up recreational and competitive fishing. Mabel Sport had this to say (in part):

I am compelled to write and let people know of the teachings I had as a child concerning the bull head. I get very hurt feelings inside whenever I hear about the Bull Head Derby. As a child I was taught about the sacredness of life. The natives believe that every living thing has a spirit. The bull head is the guardian of the waterfront and rivers. It keeps the water clean [and] guards the small coho fry until maturity. The more plentiful the bull heads are in the river, the more plentiful the fish. (Anderson, 62)

Mabel Sport’s feelings mark the relationship Northwest Coast peoples have with animals as an emotional connection, founded on deep mutual respect. In Native American Indian beliefs some nonhumans have powers far exceeding those of ordinary humans. Some animals move with ease in worlds inaccessible to humans: deep water, the air above, or the underground below; others sacrifice themselves as food. In Indian minds they are all “people.”

We can now propose a diagnosis for the human-nature disconnect as the lack of nature consciousness, delineated by these discrepancies:

Joseph Couture, a Canadian Aboriginal scholar, views “Indian Medicine” as optimistic and positive, and “discoverable by anyone who wants to ‘see’ earnestly and sincerely. Couture’s first experience with Indian Medicine, in the spring of 1971, involved a sweat lodge and pipe ceremony, a fast, and his first “Dream.” Couture went without food or water for four nights and three days, staying awake from dusk to dawn. On each of the three nights he had the same dream, the kind Plains Indians call “the Dream.” What Couture learned from the dream was what he calls “the true meaning of the Indian Way,” something conventional Christian mentality had kept in his mind’s shadow. As a result of his Dream, couture began to feel a “physical healing effect” in the sweat lodge and other ceremonies, now no longer affected by his conditioned “philosophical and spiritual disposition.” After the third repetition of the Dream, Couture notes:

My compulsive and apprehensive rational mind quietly settled into a waiting attentive mode, and with that came trusting acceptance of what began to be a deeply satisfying, in-depth Indian spiritual experience. (Indian Spirituality: A Personal Experience, 6)

It is not too presumptuous an assumption, I think, to conclude that what Couture is describing here is preparedness, and openness, to nature consciousness. Couture attributes this “waiting attentive mode” to his “absolute fast.” The fast, he explains,

…is a crucial moment, for it is then, perhaps more than at any other moment of conscious relating to Spirit, that one enters deeply into prayer and introspection, into experiences of inner and outer phenomena, into experiences of enlightenment and change. Ineluctable and ineffable moments these can be and frequently are. (7)

For those thinking “Indian Medicine” is an anachronistic and impractical practice, Couture reminds us that this is “Indian religion and spirituality as it is today,” and that more and more Natives are returning to Native spiritual leaders so they can return to Indian life principles. Indian Medicine is a therapy with potential to heal the human-nature rift through a process leading to knowing as an Indian knows and seeing as an Indian sees. Couture concludes Indian Medicine is

….as a process objective, requiring conscious sidelining of discursive reason, or the intellectual mind, to let intuition, or the intuitive mind, play. Doing this can lead one to a direct experience of the truth of the Indian Way, entering directly upon its Ground where knowing is being.

In this process a vital relationship is established with the “Great Spirit” or the “Creator,” concomitant with a feeling of balance or centredness that leads, in turn, “to a relationship with all manifestations of Being” and “gives meaning to all, to the self, to all components of one’s environment.” While Couture cautions it is difficult to describe the way the Indian mind works, he highlights that Indian Medicine brings about a unity of human and earth infused with one creative spirit. This “at-one-ness” with nature, a way of being that conforms with nature, “is the source of peace with self, for it is really a living in the Self, or self of selves, the Source of being.” For Couture, an essential consequence of the Indian Medicine process is a sense of silent “fulfilling communion,” a state of mind where analytical intellectual activity is replaced by intuition and dream activity. Such awareness is the “at-one-ness with Nature” Couture speaks of.

To pursue Indian Medicine without faltering, Couture emphasizes that whether one was raised in an Indian culture or not, elders are the ones to facilitate this process of spiritual learning in a relationship of apprenticeship. What the apprentice gains from this “learning-by-doing process” is the wisdom and capacity to shed the domination of the rationalistic mindset.

This brief exploration of Native American Indian religion proposes a therapy for attaining a way of being in the world we can term “nature consciousness,” a consciousness that embraces nature and humans as one whole. As Joseph Couture tells us, nature consciousness is available to anyone willing to pursue it diligently as a spiritual path under the guidance of elders. In a time when many Native Indians are rediscovering their traditional religious practices as therapy for their disconnect and sense of alienation from nature and culture, these same traditional practices offer non-Natives a healing process to bridge the chasm of nature-human disconnect and arrive at the harmony of nature consciousness.

Works Cited

Anderson, E. N. (1996) Ecologies of the Heart: Emotions, Belief, and the Environment. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Couture, Ruth and McGowan, Virginia, editors (2013) A Metaphoric Mind: Selected Writings of Joseph Couture. Edmonton, Alberta: AU Press Athabasca University. http://www.aupress.ca/index.php/books/120198

Deloria, Vine Jr. (2003) (first edition 1973) God is Red: A Native View of Religion. Golden, Colorado: Fulcrum Publishing.

Momaday, N. Scott (1976) “Native American Attitudes to the Environment” in Seeing With A Native Eye. New York: Harper & Row.

Standing Bear, Luther (1978) Land of the Spotted Eagle. Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press.

Introduction

Western Buddhism offers a “spiritual” path for anyone seeking an ethical life without commandments handed down by a supreme god and without requiring all-out conversion and identity change. Buddhism is unique because of its finely articulated method for developing ethical conduct, a method that begins with the individual and flows from the individual out to society. This method was developed by the Buddha with the aim of alleviating dukkha and can best be applied today to address both individual and collective dukkha. As an outreach program, a Westernized Buddhism could be facilitated by the reversal of the Buddha’s innovative “ethicization” process, in which social ethics were converted to religious ethics twenty-five hundred years ago. What best serves contemporary Western society is an adaptation of Buddhism, a form of Buddhism that retains meditation and personal ethical refinement at its core, but without the theory of rebirth and karma. In other words, the Buddhism that speaks best to Westerners is free of eschatology and soteriology, a sort of Buddhism that has been “re-ethicized” (to borrow the term from Jonathan Watts).

Richard Gombrich notes that some of the Buddha’s teachings were developed in response to the social and intellectual climate he lived in. In the Buddha’s time and place, karma meant action and was associated with ritual sacrifice. In Gombrich’s view, the Buddha redefined karma as intention rather than action and “it was intention alone which had a moral character: good, bad or neutral.” (51) For Gombrich, this redefinition of “action” as “intention….ethicised the universe” and was a turning point in the history of civilization. The Buddha converted karma as physical action to karma as psychological process. Whereas Brahmanism allowed for purification of moral misconduct by acts of physical removal of pollution, Buddhist purification of morality involved spiritual progress. The aim of the Buddhist was to purify the mind by thinking “pure thoughts of good intentional action – these were the goals of the Buddhist.” For the Buddhist monk consciousness “is an ethicised consciousness,” a consciousness that is a process, an activity. (61) For Gombrich, then, the Buddha’s redefinition of karma had two important features. First, a process replaced objects, and salvation now would come from “how one lives, not what one is.” And second, this process has been ethicised; the morally good Buddhist is the one to attain liberation.

Rebirth, karma, and Buddhist ethicization

Gananath Obeyesekere, Professor Emeritus of Anthropology at Princeton, has written extensively about the Buddha’s ethicization innovation. In Obeyesekere’s analysis, the elements essential to any rebirth eschatology are:

• an ancestor or kin is reborn in the human world;

• some essence of the ancestor lives on after death

• believers want the dead ancestor or kin to come back to this world

• believers want the dead ancestor to come back to this world and live near them

Obeyesekere uses the term “rebirth eschatology” to refer to rebirth beliefs in a society that does not have a belief in karma, while using the term “karmic eschatology” to refer to belief systems that combine rebirth with karma. He notes that small-scale societies all over the world have rebirth eschatologies, but only Indic societies have karmic eschatologies.

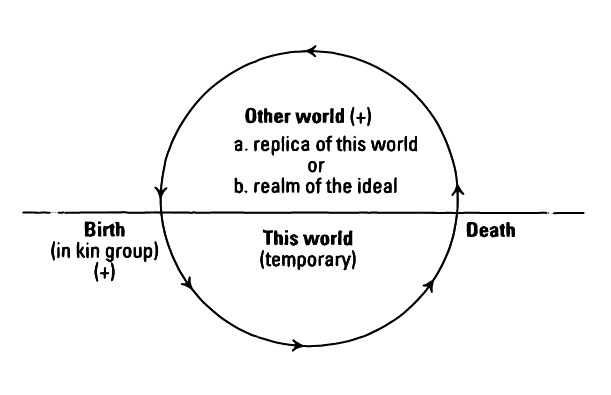

Obeyesekere’s basic rebirth eschatology (before ethicization); there are standard ways of identifying a neonate; rebirth memories are possible for ordinary folk. (73)

In the basic rebirth eschatology, the neonate is the ancestor come back to this world. Then at death, funeral rites transfer the person again to the world of the ancestors, the other world. The ideal other world is a paradise where there is no suffering. And there is no hell or a place of punishment where all bad people go. Bad people are punished by having a non-human rebirth. The difference between rebirth in small-scale societies compared with Buddhist societies is that in small-scale societies the other world is a good place and the ancestor is reborn in a good rebirth in this world. In Buddhism, on the other hand, almost all violations of ethical rules are also violations of religious rules. Consequences bad or good await in the other world. Ethicization, for Obeyesekere, is “the process that makes morally right or wrong actions also religiously right or wrong,” in a way that affects a person’s “destiny after death.” Ethicization, then, is a religious evaluation of moral conduct. The Buddha’s transformation of rebirth into an ethicised one, asserts Obeyesekere, has had great impact on “society, culture, and conscience,” a sentiment no doubt shared by Gombrich.

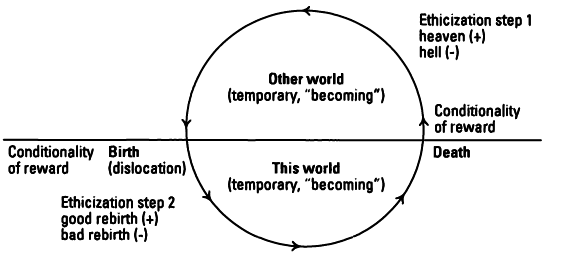

Obeyesekere’s karmic eschatology with ethicization in two steps; salvation – nirvana/moksa – takes place only outside the rebirth cycle; there are no standard ways to identify a neonate; rebirth memories are not possible except for extraordinary folk. (79)

All societies have rules for social order. But religious rules come with soteriological consequences. In Obeyesekere’s analysis, religious consequences pervade the whole eschatological sphere due to the contingency of reward and punishment. In the basic rebirth eschatology, the soul of the dead will enter the other world so long as funeral rites are performed properly. But, with ethicization, entry of the soul to the other world depends on the ethical nature of the person’s conduct in this world. And this is Obeyesekere’s key point: As a consequence of this initial ethicization of moral rules, the other world is also transformed into a world of religious consequence. Those who have died after a life of good conduct cannot be in the same place with those who have died after a life of ethically bad conduct. This is step one of the ethicization process. Now the other world is divided into one place “of retribution and another of reward.” Heavens and hells need to be invented for any ethicised eschatology, and that is why, in Obeyesekere’s view, heavens and hells can be found in Buddhism, Christianity, and Islam. The change of the basic rebirth eschatology into a karmic eschatology is a two-step process. Step one ethicizes the other world, with its heavens and hells. But with ethicization, this world (of rebirth) already has in it merit, demerit, and the contingency of reward. Logically, then, a second step must follow. The next rebirth is also ethically contingent on conduct in the preceding life in this world. One will have a good or a bad rebirth; this world also becomes a world of consequences based on ethical conduct.

Gombrich’s Buddhist monk, with his “ethicised” consciousness, lives in a world where the determination of whether he attains a good rebirth or a bad rebirth depends on the quality of his ethical conduct in previous existences. In a world requiring ethical conduct, people do good or bad, all the while accumulating merit and demerit, and then they die and do the same in the other world; and so on and so on. Ethicization, explains Obeyesekere, “connects one lifetime in this world with another in a continuing series of ethical links.” The impact on society is great because this ethicization shifts peoples’ consciousness: “It looks to them like rebirth is not an event or thing of its own but rather is a result of the ethical nature of their conduct [and]…rebirth seems as if it is generated from ethics.” (82)

In Obeyesekere’s view Buddhism systematically converted a social morality into a religious one because Buddhists wanted to make the teachings available to ordinary people, not just those interested in personal salvation, so they established the lay community and developed congregations of lay supporters. The great shift in Buddhist society was that salvation and the path to achieve it were made available to all (although not on the same terms). And this grand innovation was deliberately made to offer an alternative to the Upanishadic esoteric approach. Obeyesekere believes that ethicization of the moral life took place in a context of an intensifying relationship between Buddhist teachers and the lay community. Inviting the lay community to take part in the Buddhist path meant “conversion of the morality that governs the life of ordinary people into a religious one.” Here Obeyesekere quotes Emile Durkheim:

“Individuals cannot be moral objects onto themselves because the ground of morality is established in a moral network.” Morality means “the values needed for orderly conduct of social life….such as respect for elders, rules prohibiting theft, lying, and so on.” (112)

Obeyesekere’s thrust here is that social morality exists only in relationships with others. But while social morality links a person to society, salvation requires being apart from society. Early Buddhism, then, had two main alternate aims: one aimed at a monk’s salvific quest by ascetic withdrawal, and the other aimed at including the laypeople in the Buddhist community. These apparently conflicting aims had to be reconciled. Obeyesekere proposes that such reconciliation was achieved by allowing the monk to live on his own but also requiring that he be involved with the lay community. The Pali Canon confirms that the teachings are for monks and lay people alike, with the five precepts providing ethical rules the lay community could commit to in the process of becoming Buddhists.

The Buddhist scholar David Loy explains what he refers to as “the Buddha’s innovation” by first noting that a moral act has three elements:

• the results of the act;

• the moral rule (a Buddhist precept, Christian commandment, or ritualistic procedure); and

• the mental attitude or motivation (volition) of the actor.

As pointed out by Gombrich, Loy notes that, in the Buddha’s day, the Brahman belief in karma required performance of ritual procedures according to specific rules. The Buddha’s spiritual innovation was the transformation of ritual desire into ethical conduct based on cetana – motivation, intention, or volition. That is how the Buddha ethicised karma. Early Buddhism, then, involved spreading the teachings, on the one hand, and developing connections with the lay community, on the other. Obeyesekere proposes two reasons for these dual aims. The first was to expand the number of disciples, and the second was to create congregations. Connection with the laity was helped along by monasticism, which also developed the public sermon as a means to offer the teachings to laypeople.

Ethicization and its discontents

Obeyesekere’s Buddhist karmic eschatology consists of these elements:

• The “soul” experiences rebirths in a cycle with unlimited repetitions;

• This rebirth cycle is governed by ethical conduct that leads to good or bad consequences in the other world; karma affects present and future lives in an existence of samsara.

• Karma leads to new ideas, such as impermanence, for example. Since good and bad conduct will have consequences, life is always contingent on the vagaries of karma. Life in this world is influenced by karmic conduct in previous lives and influences future rebirths. Karma destabilizes and introduces flux. ‘Impermanent are all conditioned things,’ says the Buddha.

• Still, there is something that remains stable – the self, consisting of the five aggregates, which are also in constant flux.

• The most important feature of the basic rebirth eschatology is that it subtracts the notion of salvation from the cycle of rebirth. And in karmic ethicization neither the ethicization of the other world (step number one) nor the ethicization of this world (step number two) involves salvation. But Buddhism is deeply concerned with salvation as a driving force to explain the end of suffering in samsara. However, salvation (nirvana) can only be reached outside the cycle of rebirths. In a basic rebirth eschatology there is no end to suffering because this world where the soul is reborn is a world of suffering. But in the karmic eschatology of the Buddha it seems the situation has been made worse for the salvific aspirant, because the other world is also governed by karma. So for nirvana to have meaning, cessation of suffering must be said to come with an “end to rebirth, or the abolishing of karma.”

In Obeyesekere’s view, the deterministic nature of karma leads to confusion and anxiety. While only intentional ethical conduct carries karmic consequences, suffering can come about from causes unrelated to karma, so it could be argued that karma is not completely deterministic of life in this world. However, as the Culakammavibhnaga Sutta states, karma eventually determines everything: ‘Beings are owners of their actions, heirs of their actions; they originate from their actions, are bound to their actions, have their actions as their refuge.’ Obeyesekere sees the deterministic nature of Buddhist karma theory as a cause for uncertainty, confusion, and anxiety due to these reasons:

• Ethical misconduct leads to unhappy consequences but one is never sure how the consequences exactly relate to the misconduct or what exactly the act of misconduct was. If a young person dies from disease, people might think bad karma brought about the disease. The disease and death are specific consequences, but no one knows for sure what the misconduct was that gave the young person a load of bad karma. And the same applies for good consequences. Moreover, no one knows from the consequences (say, disease and death) if there had been any karmic misconduct in the first place. While all karmic conduct has consequences, not all consequences flow from karma.

• With Karma, ethical conduct in past lives affects this life, and conduct in this life affects future rebirth. But ordinary people do not remember past lives, so good times and bad times come and go as a consequence of conduct in past lives, lives that a person doesn’t know anything about. And, for the most part, nothing can be done to atone for past misconduct. On the one hand, karma determines (almost) everything; but on the other hand, no one knows how much or what kind of bad (or good) karma they were born with.

• Although the deterministic nature of karma seems unassailable, “the Mahakammavibhanga Sutta could justify the popular notion of counterkarma – the idea that good deeds could cancel the effect of bad deeds.” The sutta tries to explain why people who have a load of good karma might have a good rebirth or a bad rebirth, and the other way around. One’s actions fall into one of four categories:

• actions that cannot bring good results and that seem incapable of bringing good results

• actions that cannot bring good results but seem capable of bringing good results

• actions that can bring good results and seem capable of bringing good results; and

• actions that can bring good results but seem incapable of bringing good results.

Also, a highly consequential act can under some circumstances cancel out the karmic effect of a less consequential act, a result that can lead to the rationale for merit making. However, merit making suggests deliberate action can have as much karmic influence as intention (volition), which is another difficult concept to grasp.

A Buddhist commits to live by the five precepts. Obeyesekere suggests these precepts have two significant features: first, there is no categorical imperative (no god has commanded they be followed), and second, it is impossible to comply fully with all five of these precepts all of the time. And while people commit to these precepts when joining the moral community of Buddhists, that does not necessarily make for a consensus on ethical conduct. For example, it would be hard to get all Buddhists to agree about what exactly amounts to sexual misconduct. As far as Obeyesekere is concerned, then, these two features suggest these five precepts were developed with tolerance for local variations, to make it easier for local communities to integrate their values with Buddhist ethics, which enabled Buddhism to spread among peoples with varied moral codes. Since laypeople are denied salvation through the noble eightfold path, they commit to a moral code matching the religious goals available to them – that of a heaven after death and a good rebirth. The precepts provide an ethical framework for right action, mainly to promote social order and control drives and passions that tend to disturb social order. With ethicized karma, laypeople commit to avoiding bad karmic consequences by intentions and actions that produce good karmic consequences. So while the Buddha expects laypeople to form attachments and acquire possessions, they are encouraged to lead a virtuous life even though the path to nirvana available to monks is not available to them. For all Buddhists, though, life in this world involves suffering, no matter how good the rebirth. For Obeyesekere, then, what the Buddha’s innovation accomplished mainly is that life in this world is a moral experience. Everywhere there is duhkka. As Obeyesekere notes:

The whole environment of humans and animals is an ethicised world – an ethicization that…is inevitable when the notions of ‘sin’ and ‘merit’ and the accompanying principle of conditionality of reward are imposed on a rebirth eschatology. (140)

Unraveling ethicization for a modern Western Buddhism

In A Guide to Religious Thought and Practices, Shanthikumar Hettiarachchi proposes that Buddhism invites everyone “to embrace an ethical path that leads to wholesome behaviour.” Buddhism, for Hettiarachchi, runs contrary to doctrine and aims at “the sublime without ‘god talk’, proposing itself as a non-theistic tradition.” As such, the tradition presents “a cognitive ethical path with a social conscience,” complete with a “critique both of the ‘self’ and the ‘other’.” It is this critique, together with a practice promoting self-examination that leads to positive social change. Buddhism here is seen as an avenue available “both for the contemplative and the activist in society.” Hettiarachchi claims modern Buddhism is a tradition unique among the faiths because it is “bold and frontal about an ethical behaviour imperative for society-building and good governance.”

Another modern Buddhist thinker, Stephen Batchelor, in Buddhism without Beliefs, asserts that the common factor for most religions is not belief in a supreme god but rather belief in life after death. But Batchelor suggests that just because so many religions see life as continuing in some form after death “does not indicate the claim to be true.” (34) After all, religions once believed that the earth was flat. And as both Gombrich and Loy point out, it is prudent to re-evaluate today what the Buddha taught in relation to the historical and social context in which he lived. Batchelor notes the Buddha lived in a place and time where “the idea of rebirth…reflected the worldview of his time.” What Batchelor proposes is that people consider fresh the fact that the Buddha integrated the Indian notion of rebirth into his teaching. Batchelor notes what he calls “religious Buddhism” claims that without rebirth there is no point in ethical responsibility and social morality. But Western Enlightenment suggested that “an atheistic materialist could be just as moral a person as a believer.” Once this “rational” view supplanted heaven and hell, “this insight led to liberation from the constraints of ecclesiastical dogma, which was crucial in forming the sense of intellectual and political freedom we enjoy today.” Moreover, Batchelor hints at the Buddha’s own teaching in the Kalamas Sutta, with its advice to put beliefs propounded by others to several personal cognitive and visceral tests before accepting them as true. On that advice, proposes Batchelor, “orthodoxy should not stand in the way of forming our own understanding.”

For Batchelor, as for Obeyesekere, Buddhism’s karmic rebirth eschatology leads to difficult questions. Batchelor’s main difficulty is with the question of what is in effect “reborn”. Other religions assert a notion of “an eternal self distinct from the body-mind complex…. [and] the body and mind may die but the self continues.” But in Buddhism there is no similar notion of self. The Buddhist self “is a fiction” born of craving (or as Obeyesekere notes – an impermanent collection of aggregates). Various answers have been proposed for this dilemma, but Batchelor feels all of these answers are “views based on speculation.” As far as Batchelor is concerned, rebirth is integral to “religious Buddhism” only to the extent it is needed as a logical complement to the Indian notion of karma. And for the Buddha, the idea of karma had more to do with psychological process, as pointed out by Gombrich as well. For Batchelor, actions have consequences and whether a form of existence continues (or not) after death, a deceased person’s thoughts, words, and deeds leave an impression even after death. What Batchelor advocates for Buddhism is a nondogmatic approach that does not cloud ethical decision making. He proposes “shifting concern away from a future life and back to the present [with] an ethics of empathy rather than a metaphysics of fear and hope.” (37)

A re-ethicized adaptation for modern Western Buddhism

Rita Gross, a historian of religion, (see Flexer: Toward a global spirituality for peace: identity, pluralism, and Buddhism), considers pluralism as the most important challenge for religion in today’s globalizing world. Gross sees the great monotheisms as universalizing religions, where one religion is seen as universally relevant for all people, claiming exclusive truth, an attitude that naturally creates enmity. Buddhism, on the other hand, views religious diversity as “inevitable, beneficial, and necessary because of human diversity.” Gross goes even further and proposes a radical shift in attitude, beyond tolerance to “genuine pluralism,” an attitude that accepts differences between religions without judging one or another as superior. With genuine pluralism people appreciate different belief systems and “variety becomes a source of fascination and enrichment” where people share with and borrow from other religions. For Gross, religious pluralism does not lead to genuine pluralism, because genuine pluralism requires individual psychological change, something Buddhist meditation practice is especially designed to foster. Moreover, Gross posits that genuine pluralism leads to members of different groups understanding “others” as equals. In a cultural encounter of groups that provide for genuine pluralism, people often adopt aspects of another religion in a beneficially mutual exchange. What Gross advocates, then, is not far removed from the historical origin of Buddhism as a tradition founded on an alternative to the orthodoxy of its particular time and place.

In Western Buddhism today there are already examples of groups adopting an attitude of genuine pluralism. Thousands of Jews in Israel, for example, have embraced some aspects of Buddhist dharma and practice. According to Israeli sociologist Joseph Loss, Buddhist organizations in Israel mainly offer dharma and meditation courses. What is interesting, though, is that most of the Israeli dharma practitioners do not consider themselves Buddhists, or even Jewish Buddhists. For Israeli practitioners, their sense of identity influences how they perceive their practice. Most Israeli dharma practitioners do not self-identify as Buddhists, avoiding making an awkward choice between belonging to their Jewish culture or the Buddhist culture. Israelis, it seems, prefer to construct their own individual “spiritual” identity, something expressed eloquently by one of the women practitioners Loss interviewed:

If I defined myself as Buddhist, I contradict myself. I have…Israeli, East European, secular, kibbutz [and youth group] conditionings. These are the conditionings of my upbringing. Should I get into another set of Buddhist conditionings? Why should I? I don’t want conditionings! For me, Buddhism is the ability to see reality with no conditioning.”