Introduction

Western Buddhism offers a “spiritual” path for anyone seeking an ethical life without commandments handed down by a supreme god and without requiring all-out conversion and identity change. Buddhism is unique because of its finely articulated method for developing ethical conduct, a method that begins with the individual and flows from the individual out to society. This method was developed by the Buddha with the aim of alleviating dukkha and can best be applied today to address both individual and collective dukkha. As an outreach program, a Westernized Buddhism could be facilitated by the reversal of the Buddha’s innovative “ethicization” process, in which social ethics were converted to religious ethics twenty-five hundred years ago. What best serves contemporary Western society is an adaptation of Buddhism, a form of Buddhism that retains meditation and personal ethical refinement at its core, but without the theory of rebirth and karma. In other words, the Buddhism that speaks best to Westerners is free of eschatology and soteriology, a sort of Buddhism that has been “re-ethicized” (to borrow the term from Jonathan Watts).

Richard Gombrich notes that some of the Buddha’s teachings were developed in response to the social and intellectual climate he lived in. In the Buddha’s time and place, karma meant action and was associated with ritual sacrifice. In Gombrich’s view, the Buddha redefined karma as intention rather than action and “it was intention alone which had a moral character: good, bad or neutral.” (51) For Gombrich, this redefinition of “action” as “intention….ethicised the universe” and was a turning point in the history of civilization. The Buddha converted karma as physical action to karma as psychological process. Whereas Brahmanism allowed for purification of moral misconduct by acts of physical removal of pollution, Buddhist purification of morality involved spiritual progress. The aim of the Buddhist was to purify the mind by thinking “pure thoughts of good intentional action – these were the goals of the Buddhist.” For the Buddhist monk consciousness “is an ethicised consciousness,” a consciousness that is a process, an activity. (61) For Gombrich, then, the Buddha’s redefinition of karma had two important features. First, a process replaced objects, and salvation now would come from “how one lives, not what one is.” And second, this process has been ethicised; the morally good Buddhist is the one to attain liberation.

Rebirth, karma, and Buddhist ethicization

Gananath Obeyesekere, Professor Emeritus of Anthropology at Princeton, has written extensively about the Buddha’s ethicization innovation. In Obeyesekere’s analysis, the elements essential to any rebirth eschatology are:

• an ancestor or kin is reborn in the human world;

• some essence of the ancestor lives on after death

• believers want the dead ancestor or kin to come back to this world

• believers want the dead ancestor to come back to this world and live near them

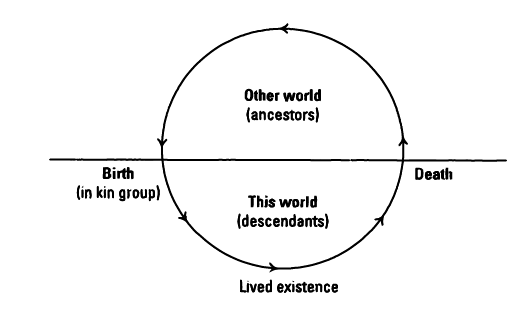

Obeyesekere uses the term “rebirth eschatology” to refer to rebirth beliefs in a society that does not have a belief in karma, while using the term “karmic eschatology” to refer to belief systems that combine rebirth with karma. He notes that small-scale societies all over the world have rebirth eschatologies, but only Indic societies have karmic eschatologies.

Obeyesekere’s basic rebirth eschatology (before ethicization); there are standard ways of identifying a neonate; rebirth memories are possible for ordinary folk. (73)

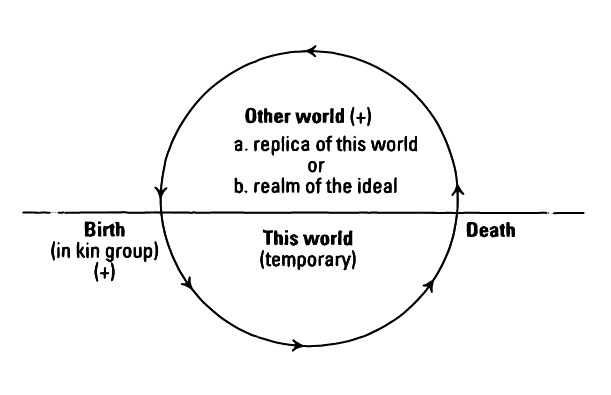

In the basic rebirth eschatology, the neonate is the ancestor come back to this world. Then at death, funeral rites transfer the person again to the world of the ancestors, the other world. The ideal other world is a paradise where there is no suffering. And there is no hell or a place of punishment where all bad people go. Bad people are punished by having a non-human rebirth. The difference between rebirth in small-scale societies compared with Buddhist societies is that in small-scale societies the other world is a good place and the ancestor is reborn in a good rebirth in this world. In Buddhism, on the other hand, almost all violations of ethical rules are also violations of religious rules. Consequences bad or good await in the other world. Ethicization, for Obeyesekere, is “the process that makes morally right or wrong actions also religiously right or wrong,” in a way that affects a person’s “destiny after death.” Ethicization, then, is a religious evaluation of moral conduct. The Buddha’s transformation of rebirth into an ethicised one, asserts Obeyesekere, has had great impact on “society, culture, and conscience,” a sentiment no doubt shared by Gombrich.

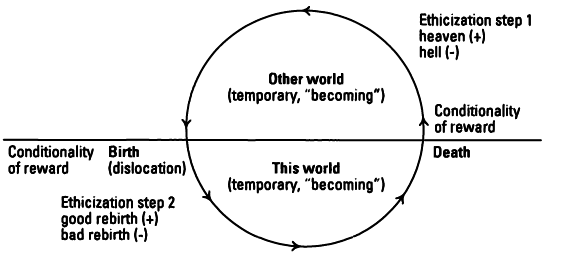

Obeyesekere’s karmic eschatology with ethicization in two steps; salvation – nirvana/moksa – takes place only outside the rebirth cycle; there are no standard ways to identify a neonate; rebirth memories are not possible except for extraordinary folk. (79)

All societies have rules for social order. But religious rules come with soteriological consequences. In Obeyesekere’s analysis, religious consequences pervade the whole eschatological sphere due to the contingency of reward and punishment. In the basic rebirth eschatology, the soul of the dead will enter the other world so long as funeral rites are performed properly. But, with ethicization, entry of the soul to the other world depends on the ethical nature of the person’s conduct in this world. And this is Obeyesekere’s key point: As a consequence of this initial ethicization of moral rules, the other world is also transformed into a world of religious consequence. Those who have died after a life of good conduct cannot be in the same place with those who have died after a life of ethically bad conduct. This is step one of the ethicization process. Now the other world is divided into one place “of retribution and another of reward.” Heavens and hells need to be invented for any ethicised eschatology, and that is why, in Obeyesekere’s view, heavens and hells can be found in Buddhism, Christianity, and Islam. The change of the basic rebirth eschatology into a karmic eschatology is a two-step process. Step one ethicizes the other world, with its heavens and hells. But with ethicization, this world (of rebirth) already has in it merit, demerit, and the contingency of reward. Logically, then, a second step must follow. The next rebirth is also ethically contingent on conduct in the preceding life in this world. One will have a good or a bad rebirth; this world also becomes a world of consequences based on ethical conduct.

Gombrich’s Buddhist monk, with his “ethicised” consciousness, lives in a world where the determination of whether he attains a good rebirth or a bad rebirth depends on the quality of his ethical conduct in previous existences. In a world requiring ethical conduct, people do good or bad, all the while accumulating merit and demerit, and then they die and do the same in the other world; and so on and so on. Ethicization, explains Obeyesekere, “connects one lifetime in this world with another in a continuing series of ethical links.” The impact on society is great because this ethicization shifts peoples’ consciousness: “It looks to them like rebirth is not an event or thing of its own but rather is a result of the ethical nature of their conduct [and]…rebirth seems as if it is generated from ethics.” (82)

In Obeyesekere’s view Buddhism systematically converted a social morality into a religious one because Buddhists wanted to make the teachings available to ordinary people, not just those interested in personal salvation, so they established the lay community and developed congregations of lay supporters. The great shift in Buddhist society was that salvation and the path to achieve it were made available to all (although not on the same terms). And this grand innovation was deliberately made to offer an alternative to the Upanishadic esoteric approach. Obeyesekere believes that ethicization of the moral life took place in a context of an intensifying relationship between Buddhist teachers and the lay community. Inviting the lay community to take part in the Buddhist path meant “conversion of the morality that governs the life of ordinary people into a religious one.” Here Obeyesekere quotes Emile Durkheim:

“Individuals cannot be moral objects onto themselves because the ground of morality is established in a moral network.” Morality means “the values needed for orderly conduct of social life….such as respect for elders, rules prohibiting theft, lying, and so on.” (112)

Obeyesekere’s thrust here is that social morality exists only in relationships with others. But while social morality links a person to society, salvation requires being apart from society. Early Buddhism, then, had two main alternate aims: one aimed at a monk’s salvific quest by ascetic withdrawal, and the other aimed at including the laypeople in the Buddhist community. These apparently conflicting aims had to be reconciled. Obeyesekere proposes that such reconciliation was achieved by allowing the monk to live on his own but also requiring that he be involved with the lay community. The Pali Canon confirms that the teachings are for monks and lay people alike, with the five precepts providing ethical rules the lay community could commit to in the process of becoming Buddhists.

The Buddhist scholar David Loy explains what he refers to as “the Buddha’s innovation” by first noting that a moral act has three elements:

• the results of the act;

• the moral rule (a Buddhist precept, Christian commandment, or ritualistic procedure); and

• the mental attitude or motivation (volition) of the actor.

As pointed out by Gombrich, Loy notes that, in the Buddha’s day, the Brahman belief in karma required performance of ritual procedures according to specific rules. The Buddha’s spiritual innovation was the transformation of ritual desire into ethical conduct based on cetana – motivation, intention, or volition. That is how the Buddha ethicised karma. Early Buddhism, then, involved spreading the teachings, on the one hand, and developing connections with the lay community, on the other. Obeyesekere proposes two reasons for these dual aims. The first was to expand the number of disciples, and the second was to create congregations. Connection with the laity was helped along by monasticism, which also developed the public sermon as a means to offer the teachings to laypeople.

Ethicization and its discontents

Obeyesekere’s Buddhist karmic eschatology consists of these elements:

• The “soul” experiences rebirths in a cycle with unlimited repetitions;

• This rebirth cycle is governed by ethical conduct that leads to good or bad consequences in the other world; karma affects present and future lives in an existence of samsara.

• Karma leads to new ideas, such as impermanence, for example. Since good and bad conduct will have consequences, life is always contingent on the vagaries of karma. Life in this world is influenced by karmic conduct in previous lives and influences future rebirths. Karma destabilizes and introduces flux. ‘Impermanent are all conditioned things,’ says the Buddha.

• Still, there is something that remains stable – the self, consisting of the five aggregates, which are also in constant flux.

• The most important feature of the basic rebirth eschatology is that it subtracts the notion of salvation from the cycle of rebirth. And in karmic ethicization neither the ethicization of the other world (step number one) nor the ethicization of this world (step number two) involves salvation. But Buddhism is deeply concerned with salvation as a driving force to explain the end of suffering in samsara. However, salvation (nirvana) can only be reached outside the cycle of rebirths. In a basic rebirth eschatology there is no end to suffering because this world where the soul is reborn is a world of suffering. But in the karmic eschatology of the Buddha it seems the situation has been made worse for the salvific aspirant, because the other world is also governed by karma. So for nirvana to have meaning, cessation of suffering must be said to come with an “end to rebirth, or the abolishing of karma.”

In Obeyesekere’s view, the deterministic nature of karma leads to confusion and anxiety. While only intentional ethical conduct carries karmic consequences, suffering can come about from causes unrelated to karma, so it could be argued that karma is not completely deterministic of life in this world. However, as the Culakammavibhnaga Sutta states, karma eventually determines everything: ‘Beings are owners of their actions, heirs of their actions; they originate from their actions, are bound to their actions, have their actions as their refuge.’ Obeyesekere sees the deterministic nature of Buddhist karma theory as a cause for uncertainty, confusion, and anxiety due to these reasons:

• Ethical misconduct leads to unhappy consequences but one is never sure how the consequences exactly relate to the misconduct or what exactly the act of misconduct was. If a young person dies from disease, people might think bad karma brought about the disease. The disease and death are specific consequences, but no one knows for sure what the misconduct was that gave the young person a load of bad karma. And the same applies for good consequences. Moreover, no one knows from the consequences (say, disease and death) if there had been any karmic misconduct in the first place. While all karmic conduct has consequences, not all consequences flow from karma.

• With Karma, ethical conduct in past lives affects this life, and conduct in this life affects future rebirth. But ordinary people do not remember past lives, so good times and bad times come and go as a consequence of conduct in past lives, lives that a person doesn’t know anything about. And, for the most part, nothing can be done to atone for past misconduct. On the one hand, karma determines (almost) everything; but on the other hand, no one knows how much or what kind of bad (or good) karma they were born with.

• Although the deterministic nature of karma seems unassailable, “the Mahakammavibhanga Sutta could justify the popular notion of counterkarma – the idea that good deeds could cancel the effect of bad deeds.” The sutta tries to explain why people who have a load of good karma might have a good rebirth or a bad rebirth, and the other way around. One’s actions fall into one of four categories:

• actions that cannot bring good results and that seem incapable of bringing good results

• actions that cannot bring good results but seem capable of bringing good results

• actions that can bring good results and seem capable of bringing good results; and

• actions that can bring good results but seem incapable of bringing good results.

Also, a highly consequential act can under some circumstances cancel out the karmic effect of a less consequential act, a result that can lead to the rationale for merit making. However, merit making suggests deliberate action can have as much karmic influence as intention (volition), which is another difficult concept to grasp.

A Buddhist commits to live by the five precepts. Obeyesekere suggests these precepts have two significant features: first, there is no categorical imperative (no god has commanded they be followed), and second, it is impossible to comply fully with all five of these precepts all of the time. And while people commit to these precepts when joining the moral community of Buddhists, that does not necessarily make for a consensus on ethical conduct. For example, it would be hard to get all Buddhists to agree about what exactly amounts to sexual misconduct. As far as Obeyesekere is concerned, then, these two features suggest these five precepts were developed with tolerance for local variations, to make it easier for local communities to integrate their values with Buddhist ethics, which enabled Buddhism to spread among peoples with varied moral codes. Since laypeople are denied salvation through the noble eightfold path, they commit to a moral code matching the religious goals available to them – that of a heaven after death and a good rebirth. The precepts provide an ethical framework for right action, mainly to promote social order and control drives and passions that tend to disturb social order. With ethicized karma, laypeople commit to avoiding bad karmic consequences by intentions and actions that produce good karmic consequences. So while the Buddha expects laypeople to form attachments and acquire possessions, they are encouraged to lead a virtuous life even though the path to nirvana available to monks is not available to them. For all Buddhists, though, life in this world involves suffering, no matter how good the rebirth. For Obeyesekere, then, what the Buddha’s innovation accomplished mainly is that life in this world is a moral experience. Everywhere there is duhkka. As Obeyesekere notes:

The whole environment of humans and animals is an ethicised world – an ethicization that…is inevitable when the notions of ‘sin’ and ‘merit’ and the accompanying principle of conditionality of reward are imposed on a rebirth eschatology. (140)

Unraveling ethicization for a modern Western Buddhism

In A Guide to Religious Thought and Practices, Shanthikumar Hettiarachchi proposes that Buddhism invites everyone “to embrace an ethical path that leads to wholesome behaviour.” Buddhism, for Hettiarachchi, runs contrary to doctrine and aims at “the sublime without ‘god talk’, proposing itself as a non-theistic tradition.” As such, the tradition presents “a cognitive ethical path with a social conscience,” complete with a “critique both of the ‘self’ and the ‘other’.” It is this critique, together with a practice promoting self-examination that leads to positive social change. Buddhism here is seen as an avenue available “both for the contemplative and the activist in society.” Hettiarachchi claims modern Buddhism is a tradition unique among the faiths because it is “bold and frontal about an ethical behaviour imperative for society-building and good governance.”

Another modern Buddhist thinker, Stephen Batchelor, in Buddhism without Beliefs, asserts that the common factor for most religions is not belief in a supreme god but rather belief in life after death. But Batchelor suggests that just because so many religions see life as continuing in some form after death “does not indicate the claim to be true.” (34) After all, religions once believed that the earth was flat. And as both Gombrich and Loy point out, it is prudent to re-evaluate today what the Buddha taught in relation to the historical and social context in which he lived. Batchelor notes the Buddha lived in a place and time where “the idea of rebirth…reflected the worldview of his time.” What Batchelor proposes is that people consider fresh the fact that the Buddha integrated the Indian notion of rebirth into his teaching. Batchelor notes what he calls “religious Buddhism” claims that without rebirth there is no point in ethical responsibility and social morality. But Western Enlightenment suggested that “an atheistic materialist could be just as moral a person as a believer.” Once this “rational” view supplanted heaven and hell, “this insight led to liberation from the constraints of ecclesiastical dogma, which was crucial in forming the sense of intellectual and political freedom we enjoy today.” Moreover, Batchelor hints at the Buddha’s own teaching in the Kalamas Sutta, with its advice to put beliefs propounded by others to several personal cognitive and visceral tests before accepting them as true. On that advice, proposes Batchelor, “orthodoxy should not stand in the way of forming our own understanding.”

For Batchelor, as for Obeyesekere, Buddhism’s karmic rebirth eschatology leads to difficult questions. Batchelor’s main difficulty is with the question of what is in effect “reborn”. Other religions assert a notion of “an eternal self distinct from the body-mind complex…. [and] the body and mind may die but the self continues.” But in Buddhism there is no similar notion of self. The Buddhist self “is a fiction” born of craving (or as Obeyesekere notes – an impermanent collection of aggregates). Various answers have been proposed for this dilemma, but Batchelor feels all of these answers are “views based on speculation.” As far as Batchelor is concerned, rebirth is integral to “religious Buddhism” only to the extent it is needed as a logical complement to the Indian notion of karma. And for the Buddha, the idea of karma had more to do with psychological process, as pointed out by Gombrich as well. For Batchelor, actions have consequences and whether a form of existence continues (or not) after death, a deceased person’s thoughts, words, and deeds leave an impression even after death. What Batchelor advocates for Buddhism is a nondogmatic approach that does not cloud ethical decision making. He proposes “shifting concern away from a future life and back to the present [with] an ethics of empathy rather than a metaphysics of fear and hope.” (37)

A re-ethicized adaptation for modern Western Buddhism

Rita Gross, a historian of religion, (see Flexer: Toward a global spirituality for peace: identity, pluralism, and Buddhism), considers pluralism as the most important challenge for religion in today’s globalizing world. Gross sees the great monotheisms as universalizing religions, where one religion is seen as universally relevant for all people, claiming exclusive truth, an attitude that naturally creates enmity. Buddhism, on the other hand, views religious diversity as “inevitable, beneficial, and necessary because of human diversity.” Gross goes even further and proposes a radical shift in attitude, beyond tolerance to “genuine pluralism,” an attitude that accepts differences between religions without judging one or another as superior. With genuine pluralism people appreciate different belief systems and “variety becomes a source of fascination and enrichment” where people share with and borrow from other religions. For Gross, religious pluralism does not lead to genuine pluralism, because genuine pluralism requires individual psychological change, something Buddhist meditation practice is especially designed to foster. Moreover, Gross posits that genuine pluralism leads to members of different groups understanding “others” as equals. In a cultural encounter of groups that provide for genuine pluralism, people often adopt aspects of another religion in a beneficially mutual exchange. What Gross advocates, then, is not far removed from the historical origin of Buddhism as a tradition founded on an alternative to the orthodoxy of its particular time and place.

In Western Buddhism today there are already examples of groups adopting an attitude of genuine pluralism. Thousands of Jews in Israel, for example, have embraced some aspects of Buddhist dharma and practice. According to Israeli sociologist Joseph Loss, Buddhist organizations in Israel mainly offer dharma and meditation courses. What is interesting, though, is that most of the Israeli dharma practitioners do not consider themselves Buddhists, or even Jewish Buddhists. For Israeli practitioners, their sense of identity influences how they perceive their practice. Most Israeli dharma practitioners do not self-identify as Buddhists, avoiding making an awkward choice between belonging to their Jewish culture or the Buddhist culture. Israelis, it seems, prefer to construct their own individual “spiritual” identity, something expressed eloquently by one of the women practitioners Loss interviewed:

If I defined myself as Buddhist, I contradict myself. I have…Israeli, East European, secular, kibbutz [and youth group] conditionings. These are the conditionings of my upbringing. Should I get into another set of Buddhist conditionings? Why should I? I don’t want conditionings! For me, Buddhism is the ability to see reality with no conditioning.”

Loss also found that the Israeli practitioners had a negative image of religion because it was a “ritualized, institutionalized, traditional, communal and oppressive blind faith, which divides people, incites communities against one another, and justifies arrogance.” (97) In spite of this, Israeli dharma practitioners look favourably on people of different faiths who, like them, prefer the “truth of ancient wisdom over science and consumer culture.” Based on studies like Loss’s, it seems fair to conclude that some Western Buddhist groups might be the epitome of the kind of genuine pluralism and mutual exchange described by Gross. They not only tolerate but appreciate other faiths, and have adopted and adapted what they consider to be the features of Buddhist practice best suited to their needs, while eschewing Buddhist eschatology and soteriology.

One particular group of Israeli Jewish “Buddhists” has adapted Buddhist meditation practice as a therapeutic educational method in their peace work. Members of Israel Engaged Dharma (IED) view peace work as part of their spiritual practice. They looked at the problem psychologists refer to as a “conflict mindset,” common in mainstream Israeli Jewish society, and developed a “spiritual” activist response to alleviate this type of dukkha. With the help of psychologists, dharma practitioners, and group facilitators, IED developed the Mind the Conflict program to help people become aware of their “hidden assumptions, entrenched beliefs, and automatic emotional patterns” (“ignorance” and “delusion” in Buddhist terms) about the Palestine-Israel conflict. Using guided vipassana meditation in group sessions with Israeli non-practitioners, IED helps to shift participants’ conflict mindset of “us” versus “them” to a mindset of peace and reconciliation.

“Western” Buddhism differs from traditional Asian Buddhism in several important ways. Four main areas of difference are practice, democratization, social engagement, and adaptation (Mavis Fenn citing Charles Prebish). For Westerners generally, as exemplified by the Israeli Jewish dharma practitioners, practice consists mainly of meditation, most often taught by lay teachers rather than ordained monks or nuns. Westerners are exposed to dharma through teachers and libraries of tapes and books, and seem naturally inclined to choose a personal path that combines elements of different traditions based on what they perceive as their personal needs. Western Buddhism is also more democratic in that there often is no distinction between the monastics and the laity. Also, advanced practice in many Buddhist groups does not require celibacy and allows for a family life. Fenn notes too that many Western Buddhists (like the Israel Engaged Dharma group) engage in social, environmental, and political activism. She supposes Western Buddhists carry with them ideas of world renovation from their original Judeo-Christian traditions and respond to world and local crises through what Thich Nat Hahn refers to as “engaged Buddhism: engagement with self, others and the world, grounded in Buddhist ethics.” Fenn sees the Western form of practice, democratization, and engagement as “adaptations of Buddhism to the West,” adaptations that discard traditional elements but keep certain desired principles in developing a specifically Western modern Buddhism. What happens in this process of adaptations from one culture to another, is that “both the donor and recipient are changed,” echoing the point made by Gross.

Jonathan Watts, in his introduction to Rethinking Karma: the Dharma of Social Justice, notes that karma is seen as both a “mysterious trajectory of fate from the past into the future” and also “intentional ethical action” in this life. Watts asserts that distinguishing between these two views is problematic for many, because it then becomes difficult to develop a consistent attitude for how to live with other people. Rather than expend great effort in trying to reconcile the complex nature of these two distinct views, or ignoring the problem altogether, Watts proposes that Buddhists embrace and promote a “personal and social ethic that encourages peaceful societies” as a model for non-Buddhist societies. Watts believes Buddhism best serves humanity by working with “other religions and value systems to craft a civilization ethics based on a dharma of tolerance, plurality, nonviolence, and justice.” Perhaps the Jewish Israeli dharma practitioners are a good example of the kind of Buddhism Watts advocates.

Conclusion

Outreach by contemporary Buddhist organizations in the West would be most effective if it emphasized certain aspects of the dharma and practice over others. Westerners seem more drawn to Buddhism’s refined ethical approach and meditation practice, while seemingly less inclined to be concerned with eschatology and soteriology. Many Westerners seek a “spiritual” path focused on ethics rather than theology. One way to view this kind of outreach program, perhaps, is by noting how it reverses the Buddha’s ethicization of twenty-five hundred years ago, in a way that adapts Buddhist dharma and practice to the time and place of the here and now. While essential cultural anchors in the Buddha’s day, nirvana, karma, and rebirth – so key for the soteriologically motivated – these seem to have little relevance for most Westerners. The Buddha’s innovation twenty-five hundred years ago in India converted social morality into religious morality. Perhaps by reversing the process (a development possibly already underway) Buddhism can best serve the spiritual needs of individuals in the West as well as the larger contemporary Western society. Western modernity has been formed by manufactured media, the bifurcation of secular versus religious categories of culture, the global flow of masses of information, and scientific knowledge displacing religion as the new faith. In this Western and globalizing world, the mode of practice of Jewish dharma practitioners – not a unique case – is, perhaps, an expression of that “spiritual” quest; a quest for a refined and well-articulated method for living a “good” life (in quality as well as ethically) and helping to change the world for the better. A project not much different from the Buddha’s original method for mitigating dukkha, both individually and collectively.

Works Cited

Batchelor, Stephen. Buddhism without Beliefs: A contemporary guide to awakening. London: Bloomsbury, 1998. Print.

Fenn, Mavis. “Western and Diasporic Buddhism” in The World’s Religions: Continuities and Transformations. Peter Clarke and Peter Beyer, eds. Pp 709-720. London: Routledge, 2009. Print.

Flexer, Jerry. “Toward a global spirituality for peace: identity, pluralism, and Buddhism.” (Unpublished) https://onlineacademiccommunity.uvic.ca/jerryflexer/ retrieved November 25, 2015

Gombrich, Richard. How Buddhism Began: The Conditioned Genesis of the Early Teachings. London: Athlone Press, 1997. Print.

Gross, Rita. “Genuine religious pluralism and mutual transformation” Wisconsin Dialogue: A Faculty Journal for the University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire 11 (1991): 35-48. Print.

Hettiarachchi, Shanthikumar. “Buddhist Thought and Practice” in A Guide to Religious Thought and Practices Patro, Santanu ed. Minneapolis MN: Fortress Press, 2015. Print.

Loss, Joseph. “Buddha-Dhamma in Israel: Explicit Non-Religious and Implicit Non-Secular Localization of Religion.” Nova Religio: The Journal of Alternative and Emergent Religions Vol. 13, No. 4 (2010): 84 – 105. Print.

Loy, David. Money Sex War Karma: Notes for a Buddhist Revolution. Boston: Wisdom Publications, 2008. Print

Obeyesekere, Gananath. Imagining Karma: Ethical Transformation in Amerindian, Buddhist, and Greek Rebirth. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002. Print.

Watts, Jonathan. “Karma for Everyone: Social Justice and the Problem of Re-Ethicizing Karma” in Theravada Buddhist Societies in Rethinking Karma: The Dharma of Social Justice. Jonathan Watts, Editor. Chiang Mai Thailand: Silkworm Books. 2009. Print.