Pre-Site Visit Reflection

The 2008 Memorial to Homosexuals Persecuted under National Socialism was erected to commemorate those persecuted for their sexuality under the Nazi edition of the anti-homosexuality law Paragraph 175. Although the law itself exclusively concerned gay men, other queer people were persecuted under the Nazi regime. Over 50,000 convictions were made under the 1935 edition of the Paragraph 175 law during the Nazi regime, and thousands of gay men were sent to concentration camps, marked with the pink triangle, and killed.

The Memorial to the Homosexuals Persecuted under National Socialism was the first national memorial to homosexuals victims of Nazi persecution in Germany. Unlike previous memorials in Germany that use the imagery of the pink triangle, the monument designed by Danish artists Michael Elmgreen and Ingar Dragset is a large asymmetrical concrete stele with a small window, in which a video of a homosexual couple kissing is played on loop.

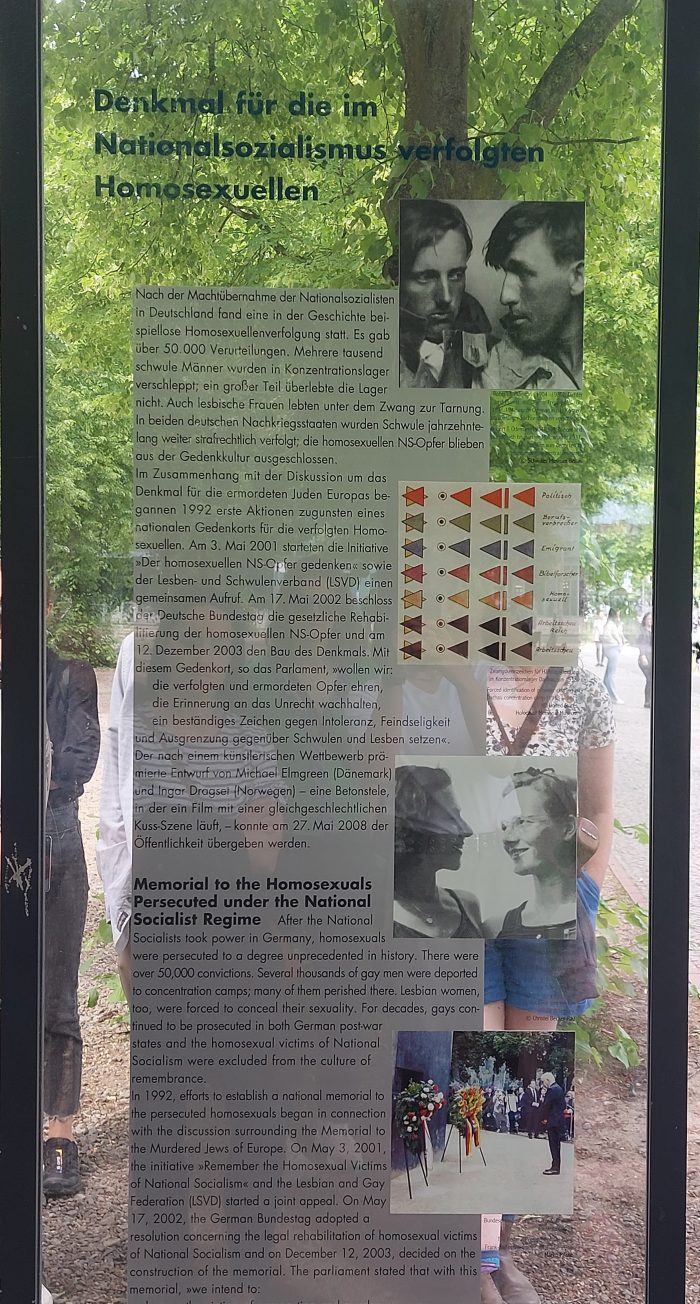

The groundwork for the memorial was laid in 1999 with the Bundestag resolution to authorize the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe (MMJE), which contained a clause obliging Germany to commemorate the other victims of National Socialism. In 2001, the LSVD (Lesben- und Schwulenverband in Deutschland [Lesbian and Gay Union of Germany]) and the Remembering the Homosexual Victims of National Socialism Initiative petitioned for a national memorial. The Bundestag resolution to fund the construction of a national monument to homosexual victims of National Socialism in Berlin occurred on December 12, 2003, and the design proposed by Elmgreen and Dragset was announced in 2006. From the 1990s onwards, there was debate about the inclusion and exclusion of lesbians in the national memorial. This debate postponed the planned 2007 construction of the memorial, and resulted in a compromise in which every two years, the video would switch between footage of two men and two women. The monument was erected on May 27, 2008, at Ebertstraße 10785 on the edge of Tiergarten Park (an area of historical gay significance) across the street from the MMJE. There is an accompanying signboard with text in German and English giving a brief history of the Nazi Paragraph 175, noting that lesbians also suffered persecution despite their exclusion from P175, and acknowledging the continued persecution of homosexuals after the Nazi period.

Amid discussions of memorialization, the Bundestag issued an official apology to homosexual victims of Nazi persecution and nullified the Paragraph 175 convictions under the Nazi regime on May 17 (17.5), 2002. This made living survivors eligible for full restitution and financial compensation; however, by 2008, many survivors had already passed away. In being tied to Nazi-era Paragraph 175 convictions, the apology and annulment did not apply to other queer people persecuted under Nazism, nor to those convicted of violating Paragraph 175 in West Germany between 1949-1969, despite these convictions being under the Nazi version of the law. This apology therefore cast the German state in a progressive light while omitting the continued willing and active enforcement of Nazi law. The signboard, although more inclusive than the 2002 apology, similarly works to cast the German state in a progressive light while omitting the continued existence of Paragraph 175 in the criminal code until 1994.

The tension between artist intention and public reception is made clear in the different perspectives on this memorial and its similarity and proximity to the MMJE. Elmgreen envisioned the form and location of the memorial as a way of both situating the victims as part of the broader history of Nazi persecution, and simultaneously showing the particularity of the experience and history of homosexuals in Germany, but others view it as a further exclusion of homosexuals from Holocaust memory. The size and placement of the window has also been criticized for its lack of accessibility and for potentially reinforcing the idea of homosexuality as something to be hidden from public view.

As we visit this and all other memorials, the questions of memorial location, form, accessibility, and inclusion will certainly come to mind.

Post-Site Visit Reflection

Our visit to the Memorial to the Homosexuals Persecuted under National Socialism highlighted the significance of place-based learning, as there were two aspects of the memorial that had not been documented in the sources I found in my pre-visit research.

The first was a signboard near the footpath on Ebertstraße that was more immediately accessible to passersby than the original plaque, and included sourced photographs of the concentration camp badge system, of homosexual couples, and of the memorial itself. It also gave information on the process of establishing the memorial as I discussed in the pre-visit blog post, from the initiation in connection with discussions of the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe in 1992 [which my pre-site research dated to 1999], activist efforts in 2001, the 2002 Bundestag resolution, the 2003 decision for construction, and its 2008 establishment. The second difference was that the video within the window of the memorial showed footage of both male and female same-sex couples kissing, alternating between couples every minute or so rather than every two years, as stated in sources. My primary research source was from 2022, suggesting that this change occurred recently. The footage was overlaid on top images of homosexual persecution as well as homosexual life and resistance (which, I was told, is also a new addition as of at least 2018), including a photo of two men about to be hanged, a photo of “Homosexuelle Aktion West Berlin” and other protests, photos of same-sex couples in everyday contexts, and of Magnus Hirschfeld’s text “Vom Dritten Geschlecht” (“On the Third Sex”). This change of the footage may have both positive and negative effects. For example, footage of post-war queer life, love, and community emphasizes the continuation of queerness after the Holocaust, and simultaneously highlights the continued existence of homophobia and the struggle for rights and recognition, while images of pre-war queerness provide evidence of historical queerness and can emphasize the humanity of those persecuted by the Nazis. However, such footage may be seen as negatively impactful or questionable; for example, the image of the two men about to be hanged. If it is a staged post-war photograph, it may be harmful in its “inauthenticity,” lending to arguments against the reality and severity of homosexual persecution during the Holocaust. If it is a genuine photograph, it may be seen as dehumanizing, as there is no information about the photo regarding its subjects, location, or time, and therefore reduces the individuals to mere victim status. Furthermore, the inclusion of post-war imagery may detract from the specific context of the memorial to commemorate those persecuted under National Socialism, and may be seen as an ahistorical representation of Nazi homosexual persecution, which was based on homosexual behaviour rather than the modern homosexual identity. While I am able to form these critiques in retrospect, the fact that I did not do so at the time and was instead moved by the memorial suggests that this edition of the video is beneficial rather than harmful to the goal of the site.

Some have criticized the resemblance of the Memorial to the Homosexuals Persecuted under National Socialism (MHPuNS) to the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe (MMJE) as equating the Holocaust experience of homosexuals and of Jewish people, either undermining the extent of Jewish persecution, or reinforcing earlier erasure of non-Jewish victim groups from Holocaust memory. However, I found the resemblance of the MHPuNS to the MMJE deeply impactful when considering how the persecution of homosexuals in Nazi Germany differed so greatly from that of Imperial and Weimar Germany, and how Nazi homophobia was grounded in the “racial” framework primarily established to target Jewish people. Unlike in Imperial and Weimar Germany, Nazi persecution of homosexuality was far more extensive, and the homophobic rhetoric framed in racial ideological terms that closely mirrored antisemitic rhetoric about Jewish males ‒ depicting them as being simultaneously predatory and posing a threat to the “Aryan race,” yet also weak and effeminate in body and character. The difference between pre-war and Nazi homophobia highlights the fact that the scale and means of homosexual persecution during the Nazi regime must be considered within the context of, and as being possible due to, antisemitic “racial” ideology and violence. As such, I found the MHPuNS to be effective in contextualizing the persecution of homosexuals in the Holocaust, particularly since we had visited the MMJE immediately prior to the MHPuNS.

There was a relative lack of information on Nazi persecution of lesbians, something that has been subject to extensive criticism. If the memorial is centering the racial ideology that formed the foundation of Nazi persecution, the lack of detail on lesbian victimization may be due to the fact that female homosexuality did not pose the same “racial threat” as male homosexuality. However, as the informational signs situate Nazi persecution of homosexuals within a broader context of pre- and post-war homophobia rather than racial ideology, this absence of information on lesbian persecution effectively marginalizes their experiences. While those with extensive knowledge of Nazi homophobia may read between the lines and view the lack of detail on lesbian persecution as a result of the specific ideological and legal differences between the persecution of male and female homosexuality, the general public may view interpret this lack as suggesting that lesbians did not suffer from Nazi persecution in a meaningful way, further marginalizing their experiences. This demonstrates the limitations of memorials as educational tools, as the necessary context for understanding the process of victimization can not always be given, especially when the methods of persecution differ within the group being memorialized, and when persecution occurred through less categorical frameworks.

Though it is not without fault, I found the Memorial to the Homosexuals Persecuted under National Socialism to be very effective in encouraging humanized memory of those it commemorates and in highlighting the difficulties of relying on memorials for education. It also demonstrated the significance of experiential learning, and how memorials can change over time in ways that may only be observable in person.

Citations:

Newsome, W. Jake. Pink Triangle Legacies: Coming out in the Shadow of the Holocaust. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press, 2022.

Simone Stirner. “Memory in the Closet? Queer Memorials After National Socialism,” PLATFORM, October 16, 2023. https://www.platformspace.net/home/memory-in-the-closet-queer-memorials-after-national-socialism Times, CC BY-SA 3.0.

The front of the memorial. Denkmal für die im Nationalsozialismus verfolgten Homosexuellen in Berlin. July 12 2008. Wikipedia, accessed April 29 2024 https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=4586636