Introduction

This exhibition will introduce readers to the Bayeux Tapestry that appears to depict the events of the Battle of Hastings of 1066. Our hope is that by understanding both the historical recording of the event and comparing it to linen production, we will be able to obtain insight into the lives of individuals in Medieval England.

The use of Linen

The origin and production of linen in Medieval England is complicated and varies depending on your sources. “Linen” was very much a “collective term” used to describe fabrics made from different fibres (North, 2020, p. 117). Simply put, linen is fabric made out of cotton, hemp, or flax. It has multiple uses including bedding, tableware, and clothing. These fabrics were not only employed in the domestic sphere but were also essential for ropes, packaging, and netting (North, 2020. p. 117).

Until the 1800s, production of cotton was favoured instead of linen. It became a specialized item used for luxury clothing (Fuller, 2015). Linen is now associated with higher-end brands but is slowly coming back into the mainstream because of its sustainability (Linen Sustainable, 2021).

Linen clothing

Though linen was a popular fabric for undergarments during the Middle Ages, that was not its only use. Linen was used to create short shirts, braies (a type of thick pants), and dresses for children because of how easy the material is to clean (Piponnier & Mane, 1997, p. 22).

Between the 13th and 15th centuries, linen was also used for headdresses, including coifs, a type of close-fitting cap, and cauls, a similar style of cap that covers tied-up hair. Linen veils were also popular for women (Piponnier & Mane, 1997, p. 22).

Courser-woven linen was used for smocks and pinafores, and there is even evidence that the fabric was waxed to make waterproof outer garments and to cover windows (Piponnier & Mane, 1997, p. 23).

Our focus on linen in this gallery is because it forms the background cloth of the Bayeux Tapestry. Despite the name, this artifact is in fact an example of medieval embroidery, not woven tapestry (Bayeux Musuem, 2023). Linen was a popular base fabric for larger, “less elegant” pieces of embroidery used for furnishings (Labarge, 1999, p. 79).

The Battle of Hastings

The Battle of Hastings is one of the most important victories for the Norman conquest of England. Duke William of Normandy and his troops crossed the English channel at Hastings on October 14, 1066 and in doing so, changed the course of English history forever (English Heritage, 2023).

But why were the two at odds in the first place? Check out this video from English Heritage to find out:

The location of Hastings for William the Conqueror’s battle against Anglo-Saxon rule is famously depicted in the Bayeux tapestry. The events that led to William’s invasion seen in the tapestry began during King Æthelred II’s reign from 978 to 1016 AD (English Heritage, 2023). Hastings is located near the southwest coast of England, which would have made it a pristine site for trade networks (Haslam, 2021, p. 142). Based on landscape evidence there, doesn’t seem to be a long history of development before the Conquest took part. King Æthelred II is supported in literature to have build burhs and defenses around Hastings to protect the town from Viking invasion in 990 AD (Haslam, 2021, pp. 136-137).

There is also archaeological evidence from the settlement that examines the building’s remains in comparison to the tapestry to determine historical accuracy. Because of previous defenses built during the King Æthelred II’s reign, it has been theorized that William the Conqueror chose Hastings as his military command before the battle took place (Haslam, 2021, p. 126). Other settlements in the tapestry, such as a church and gate-tower, are perceived to have existed in Hastings before the Conquest because of motif designs (see Figure 1).

The Two Sides

Harold’s Army

- Estimated to be between 5,000 and 7,000 men

- Housecarls, which were a type of specially trained infantry, carrying two-handed battle-axes

- Fought on foot, only used horses to arrive at the battlefield

- Few archers

William’s Army

- Estimated to be a similar size to Harold’s

- Used crossbows

- 2,000 to 3,000 man cavalry (fighting while on horseback)

- Included Norman, Breton and French soldiers

The battle lasted nine hours and took place on a vast field north of Hastings, which is at the southern, central point of Great Britain (English Heritage, 2023).

William’s quick, horse-powered army broke through Harold’s line of warriors, helping him to win the battle. The fight was bloody and produced many casualties, including the armies’ many horses. It is reported that William had three horses die from beneath him during the course of the battle (English Heritage, 2023).

Harold himself was killed and his body was severely maimed as one of the final acts of William’s victory (English Heritage, 2023).

Why was the Battle of Hastings so significant?

The Battle is significant for many reasons, but one of the most notable is King William I’s ascension to the throne, marking the first Norman King of England. This brought Britain closer to the rest of the continent and, more notably, France. French influence spread across the country. It was a time of great upheaval — the Norman rule saw the creation of the common law, as well as how it was governed, its language, and their customs. (English Heritage, 2023).

The Battle of Hastings saw the start of a new age in history, and William I left his mark on the throne forever after.

But how do we know all of this? And how is it related to linen, of all things?

The Bayeux Tapestry

The Bayeux tapestry was first found in the treasury of the Bayeux Cathedral and was eventually removed in 1794 by the Art Commission for Bayeux (Bayeux Museum, 2023). It then continued to be passed around Europe until its permanent display in 1983 at the Bayeux Museum (Bayeux Museum, 2023).

The Materials and Designers

The tapestry is made up of an array of different linen pieces embroidered with images, ranging from buildings, soldiers, animals, armor, and latin text etc. (Pastan & White, 2014). There’s also a range of theories trying to determine when the tapestry was actually made, most of which focus on its creation during King William’s reign from 1066-1087 (Pastan & White, 2014, p. 2).

Following this hypothesis, it would have been made at St Augustine monastery in Canterbury. Despite this, there are debates on whether monks or women embroidered the tapestry (Pastan, 2014, p. 13). It could indeed be a combined effort, but some scholars point to women primarily working on clerical textiles as an indicator of their involvement (Pastan, 2014, p. 13).

The Narrative

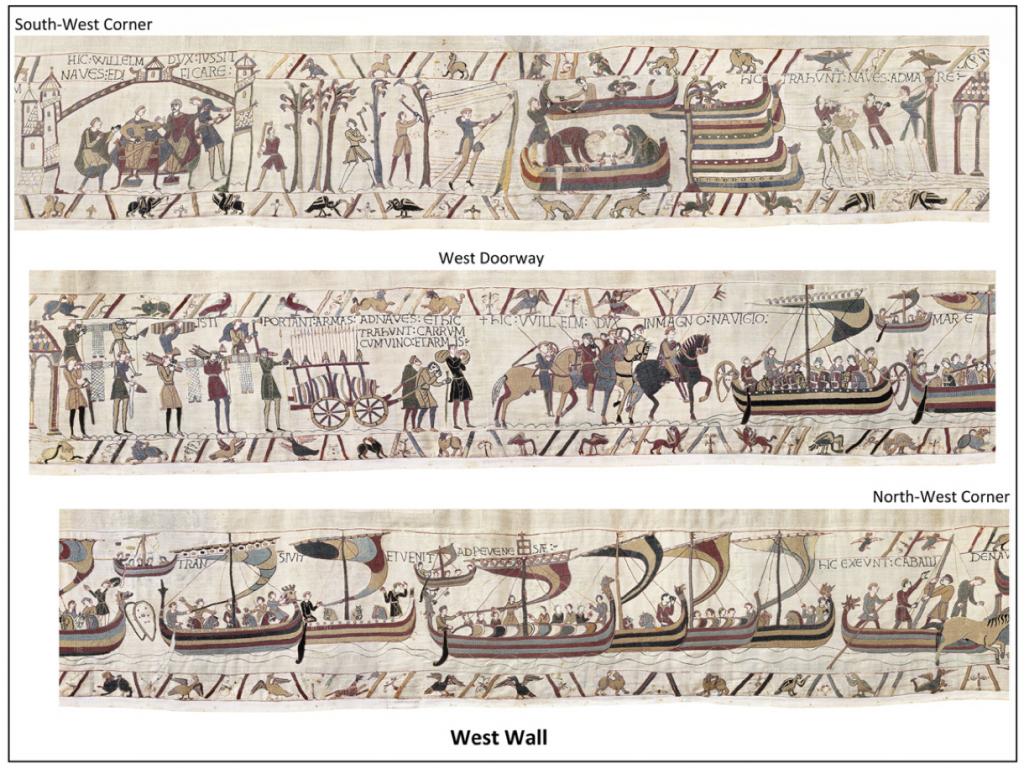

The textile piece spans over 224 feet in length, with many theories wondering how it ended up at the Bayeux Cathedral (Pastan & White, 2014, p. 1). One assumption claims that it was built for the 11th century Cathedral, but some critics have studied its configuration and reject this hypothesis (Norton, 2019). While its journey to Bayeux, France still remains unclear, the majority of literature accepts that it depicts the events that led to the Battle of Hastings of 1066.

There are three main sections that each illustrate a different narrative, but all remain questioned on their historical accuracy (White, 2014). It first shows Duke Harold’s interactions with Duke William and his return to King Edward of England. The second section shows the death and burial of King Edward where Harold eventually becomes King. Lastly, it depicts the battle and Harold’s death which would then lead to William I reign as King (Pastan & White, 2014, p. 3).

Visit this link to view each scene from the tapestry: Bayeux Tapestry

Interpretations drawn from the Tapestry and its overall importance

The Bayeux Tapestry and many tapestries of the time serve as a way to document important battles. There are a number of details that have been helpful in researching the battle. A lot can be interpreted about battle, dress, and both Norman, and English history from the tapestry.

When researching the Battle of Hastings, it is nearly impossible to read materials that do not reference the tapestry as a source of information, from the suspected cause of death of King Harold from an arrow to the eye (English Heritage, 2023), to the food preparation processes of King William’s servants before going to war (The National Archives, 2023).

For example, the clothing depicted on the figures can tell us how military personnel ranked. The Dukes were depicted with elaborate costumes. Duke William is depicted on an ornate stool and with tassels on his collar. The specific way in which the figures are depicted also helps historians identify which side the men are on to further understand the battle. Other identifiers include the kind of moustaches the men have.

It’s no surprise, then, that the Bayeux Tapestry has had a profound impact on the understanding of the Middle Ages in England and Normandy. It is seen as one of the most useful sources for interpreting both big events, like the Battle, but also the daily life of people during this time (The Bayeux Museum, 2023). The tapestry holds much of the information we know about the Battle of Hastings making it an integral part of Medieval history (Hicks, 2007).

Another Bayeux Tapestry?

There has been some argument about the rightful and final resting place of the Bayeux Tapestry. After visiting the Bayeux Museum in the late nineteenth century, a woman named Elizabeth Wardle decided that England deserved its own replica (Reading Museum, 2023).

The replica is on display at the Reading Museum in Reading, England. Though the group of 35 women who worked on the embroidery were directed to recreate it as accurately as possible, slight variations exist that are indicative of social values in the Victoria era (Reading Museum, 2023).

For example, below you can see how underwear was added onto this man after the staff who took the women’s reference images had drawn it in as a classically Victorian act of decency.

Conclusion

- Pieces of art, including tapestry and embroidery, should not be dismissed as decorative and should instead be appreciated for their value as historical documents.

- The Early Middle Ages in England were a time of political and cultural transition, greatly influenced by the Norman conquest.

- The Bayeux Tapestry is the ultimate source for information about the Battle of 1066.

Further Explorations

Curious about other another historical tapestry?

- The Oseberg Tapestry, found in the Oseberg shipwreck in 1903

- Price, N. (2022). Performing the Vikings: From Edda to Oseberg. Religionsvidenskabeligt Tidsskrift, 74, 63–88. https://doi.org/10.7146/rt.v74i.132101

Want to try designing your own Bayeux Tapestry-inspired artwork?

- Visit this website to try it out!

Dying for a catchy song to remember the tapestry by?

- Check out this song!

Leave a Reply