The War Begins: “Remember Nelson and the British Navy. All Canada is watching”

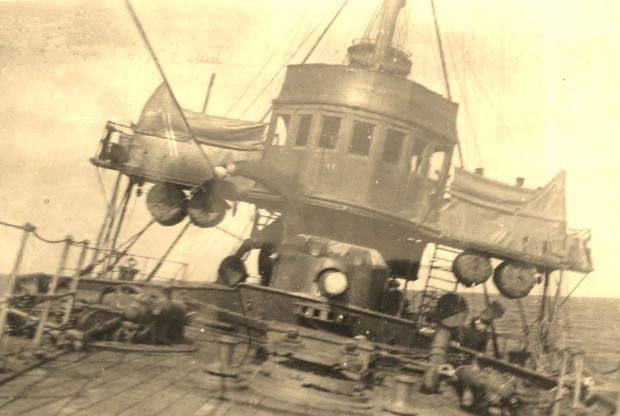

Image Source: Victoria Maritime Museum

On August 4th, 1914, Great Britain declared war on Germany. The Rainbow had already been ordered to sea two days prior with the seemingly impossible task of protecting “trade routes north of the equator.”[1]. Upon learning war had been declared, Commander Hose immediately had the ship fire its guns for calibration and practice.[2] News soon came that proper high explosive ammunition for the ship’s guns had arrived in Esquimalt by train. Hose immediately headed on a bearing for home. The Rainbow had half of its compliment of crew, and significant portion of these were brand new volunteers with little to no training.[3] Yet as the Rainbow steamed for home, an urgent telegram reached its wireless set.

[German cruisers] NURNBERG and LEIPZIG reported August 4TH off Magdalena Bay steering north. Ends. Do your utmost to protect [British sloops] ALGERINE and SHEARWATER steering north from San Diego. Remember Nelson and the British Navy. All Canada is watching.[4]

The two British sloops were in imminent danger if they encountered the roving German cruisers. Rainbow was the only allied ship in the West Pacific that could offer assistance.[5] Upon receiving this message, the Rainbow reversed course and began heading south. Even with all its deficiencies, the ship was ready to engage the enemy if necessary.

The Victoria press had gotten wind of the Rainbow’s departure and that a German cruiser was reported in the area. A.F. Duguid, the official historian of Canadian involvement in the First World War, detailed the panic that gripped British Columbians at this alarming news.

“The reported presence of two German light cruisers off the Pacific coast gave rise to popular apprehensions of attack on Vancouver, Victoria or Prince Rupert. For the next three weeks there was widespread alarm, the banks shipped their gold reserves to Seattle or Winnipeg and arranged to burn their paper currency if the Germans landed, and some people fled inland. On 8th August the D.O.C. was ordered to “be ready at a moment’s notice to mobilize all troops on the coast to guard every coal dock.”[6]

Although this hysteria gripped the psyche of many civilians, the press reported favourably on the Rainbow. According to the Victoria Times, the Rainbow “was a faster boat mounting two six inch guns, [Rainbow] is more than a match for the German boat.”[7] This was an optimistic outlook at best. The more modern German cruisers were superior to the Rainbow in all other ways unmentioned.[8] It was well understood by many who saw the ship leave Esquimalt, that they may never see the Rainbow again.[9]

“Operating Alone on a Very Dangerous Mission”: The Rainbow patrols the Pacific.

The Rainbow was bound for San Francisco on August 5th, and according to her ship’s log, the crew began “preparing [the] ship for battle when everyone developed a craze of throwing overboard everything that was movable.”[10] The anxiety amongst the crew was infectious; the threat of battle seemed imminent. She reached San Francisco by the 7th, and set about attempting to coal from the neutral American port. Commander Hose received many conflicting reports of German cruiser activity while in harbour, and had no contact with the two sloops he had been sent to protect.[11] Orders from Admiralty confirmed that the Algerine and Shearwater were already north of San Francisco, and Rainbow set out in search of them. Again, the crew began tearing out any unnecessary woodwork that may catch fire and tossed it overboard into San Francisco harbour.[12] When this flotsam was discovered near the Golden Gate Bridge, and its origin was determined to be the Rainbow, some anxiety was caused; it was assumed she had been lost in battle.[13] In reality, she was patrolling around the Farralone Islands just off of San Francisco in search of her two wards. The German cruiser Leipzig was also in the area at this time, and if not for thick fog surrounding the area the two ships would have certainly made contact.[14] On the 10th, the Rainbow steamed north to a rendezvous point in hopes of keeping the Germans between her and the sloops. When the other ships did not arrive at the rendezvous, Commander Hose had to head back to Esquimalt. Her coal deposits were running dangerously low.[15] The sloops were still missing, the enemy had not been contacted, and the Rainbow was reluctantly forced to head home.

On the morning of August 12th, the Rainbow crew was hastily called to action. An unidentified warship had been sighted! Upon further inspection, the “enemy” turned out to be the Prince George; a Grand Trunk Pacific railway steamer fitted as a hospital ship to assist the Rainbow.[16] Both ships turned for home. Twenty miles outside of Esquimalt they encountered the Shearwater, whose captain was still unaware that war had been declared. [17] Arriving home on the 13th, no word of the Algerine was available. After a brief respite and recoiling in Esquimalt, the Rainbow prepared to set out in search for her.[18] A compliment of high explosive shells was put on, but much to the chagrin of the gunners, the shells had no fuses and were decidedly useless.[19] A small number of the crew, who according to the ship’s log had “had enough of the sea,” were discharged and new volunteers were taken aboard.[20] The Rainbow left base on the 14th, at full speed in search of the lost sloop. The Algerine was sighted taking on coal from a passing ship the next afternoon.[21] When the Rainbow came upon her, the captain of the sloop signaled “I am damned glad to see you.”[22] The two ships reached home on the evening of the 15th; both sloops were now safe in harbour.[23] The Rainbow had completed its first mission, and had sustained no casualties; however, the war was far from over.

“Unhappy Cruiser Leipzig!”: Allied Presence in the Pacific Grows Stronger

Although the Rainbow had successfully escorted the two sloops home, British Pacific Coast shipping was still in danger from the roving German cruisers in the region. Rumours abounded of ships being captured and plundered by the Germans in the waters outside San Francisco. These stories “paralyzed the movements of British shipping from Vancouver to Panama.”[24] On the 13th of August, the captain of the Leipzig sailed into San Francisco harbour and boasted “We shall engage the enemy whenever and wherever we meet him. The number and size of our antagonists will make no difference to us.”[25] This could be interpreted an insult to British naval power in the Pacific, but also as a challenge to the Japanese cruiser Idzumo which was present on the West Coast.[26] Although Japan would not declare war on Germany until the 23rd, the Idzumo’s captain had made it clear he intended on shadowing the Leipzig as it conducted operations.[27]

Upon learning of the Idzumo’s intentions, the Victoria Times reported under the headline “”Unhappy Cruiser Leipzig!” that the German cruiser will “be stalked wherever she may go by a warship big enough to swallow her in one bite.”[28] Another boon to the protection of British Columbia came in the form of two submarines. Right before war was declared, the B.C. Government had secured two submarines originally intended for the Chilean Navy from an American shipbuilder. These subs marked an unprecedented purchase of military equipment by a Province. Although it took time to crew and arm them, their presence was seen as deterring German movements northward.[29] As the Japanese entered the war, and the British began establishing a stronger presence in the Pacific, the waters of the region were only to get more dangerous for the Germans.

Reinforcements Arrive: The Rainbow Fades, as its Role Declines.

On the 18th of August, a Bristol class cruiser, the Newcastle, was dispatched from Japan to Esquimalt. This was a much more powerful ship than the Rainbow, or any German cruiser in the Area for that matter.[30] On the same day the Rainbow received orders to “proceed and engage or drive off Leipzig from trade routes off San Francisco.”[31] The Rainbow eagerly readied for this fight, only to have the orders rescinded. Apparently two German cruisers were in the area, and the admiralty was not willing to sacrifice her in a clearly unequal struggle.[32] An enemy presence was reported off of Prince Rupert the next day. The Rainbow steamed up the coast at full speed, and Commander Hose gained the impression that German cruisers had coaled from American ships in the area.[33] Ultimately, all of these suspicions would prove to be rumours. There was no German presence north of San Francisco during this period.[34] Regardless of the Rainbow’s tenacity to join the fight, her role was set to diminish. On August 25th, the Idzumo sailed into Esquimalt.[35] The Newcastle arrived five days later; the same day the Rainbow returned from the North.[36] She was now far from the only significant allied presence on the West Coast, and the German cruisers of the Pacific were in no place to contend against these new arrivals.[37] The burden of West Coast defence was now removed from the Rainbow and her crew.

The Rainbow was not fully removed from combat duty at this point. As the Idzumo and Newcastle sallied into the waters off San Francisco, the Rainbow was left behind guarding the colliers supplying the larger and faster ships.[38] Their search was in vain. The German cruisers who had been terrorizing the British shipping had now joined a much larger force pushed out of the South Pacific by Japan’s entry into the war. [39] This force was attempting to return to the Atlantic, and the British were determined to stop it at all costs. The Rainbow was put under direct admiralty control, and was assembled off of Mexico with British, Japanese, and Australian forces, in an attempt to intercept the escaping Germans.[40] On October 9th, this force was dispatched from the waters off of San Diego to find the enemy; however, the Rainbow was to be left behind.[41] Upon receiving this news, Commander Hose immediately requested by telegram that the ship be included on the mission.

Submit Admiralty may be asked to arrange with senior Naval Officer of the Allied Squadron assembled off San Diego that RAINBOW shall, if possible, be in company with squadron when engaged with enemy. [42]

Hose’s request was soundly dismissed by a curt reply from the Admiralty.

There are many reasons for not complying with your request. A matter of sentiment cannot be considered as excuse for asking Admiralty to alter their arrangements. They are very much occupied. Another thing, if RAINBOW were lost immediately there would be much criticism on account of her age being sent to engage modern vessels. Can quite understand your anxiety to take a more active part in operations… [but] one cannot do more than his best. [43]

The Rainbow was ordered back to Esquimalt to act as a messaging relay between Esquimalt and the Allied Squadron.[44] In December, the ship was tasked with removing guns from coastal defences in Seymour Passage, and with assisting British shipping in the area.[45] The threat from the Germans was dissipating.

In January of 1915, the Rainbow was ordered back off of Mexico to patrol for the German cruiser Dresden, a remnant of the German force the Rainbow had desperately wanted to pursue.[46] The German squadron had been smashed off of the Falklands by a powerful British fleet after they had destroyed a smaller British force the previous November. Although the Rainbow would have been in grave danger had it confronted the Dresden, it was ordered to find the ship then flee so larger ships could be brought to bear.[47] The Dresden was eventually located in the South Pacific and sunk in March 1915.[48] Once again the Rainbow was ordered home. After this date, she was effectively removed from combat danger for the rest of her service.

‘Performing an Unusual Service’: the Russian Gold Bullion Exchange

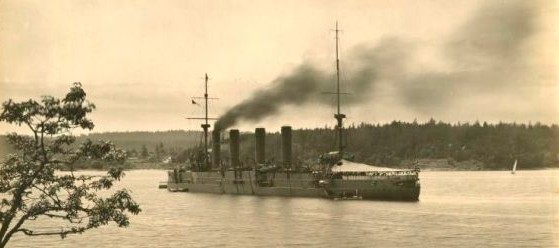

Photo Source: Maritime Museum of British Columbia

The Rainbow remained busy in the period up until 1917, patrolling for German shipping and raiders. She seized several ships during this time, and had a full crew and a collier to supply her on cruises.[49] On several occasions during 1916 and 1917, she was involved in the transfer of gold bullion from the Russian Government facing revolution back home. Large amounts of gold came across the Pacific on Japanese ships, and was transferred to the Rainbow in clandestine operations on the isolated West Coast of Vancouver Island.[50] In all nearly $140,000,000 worth of gold was transported by the Rainbow.[51] This was quite a sum for a dilapidated cruiser purchased for a lowly £215,000 six years earlier.

Rainbow Retired: She is paid off, the Crew Shipped out, and the War Comes to an end.

By 1917, the Pacific Coast of North America was no longer in need of the Rainbow’s service. The Japanese had long secured the North Pacific. With the American entry into the war on April 6th, 1917, there was no more German shipping along the Coast to harry.[52] Meanwhile, there was difficulty manning East Coast naval operations, and the Rainbow was increasingly being recognized as entirely obsolete.[53] By the end of April, the Admiralty was making plans to decommission her.[54] She performed her last duties by training gunners for the Eastern patrol vessels, and was paid off (meaning crew was entirely compensated and disbanded), on May 8th, 1917.[55] She was converted into a depot ship in June, and remained in Esquimalt making short voyages around Vancouver Island for occasional training of new officers.[56] As the war raging in the Europe played itself out, the Rainbow was effectively out of naval service.

After the war, the Rainbow languished at dock until purchased for $67,777 dollars by an American scrap metal company. In September 1920, she was shipped out of Esquimalt; so ended the career of one of the first ships to Sail for Canada’s navy.[57] She would not last long after her sale, as she soon sunk being towed outside of Seattle while loaded up with copper ore.[58] The Rainbow had performed well in her duties, and was far more active during war than ever had been planned. Although she never actually saw combat, the Rainbow performed gallantly as one of the first ships in the Canadian Naval Service, and she left a lasting legacy that exists to this day.

Image Source: Maritime Museum of British Columbia

Footnotes

[1] Ibid, 11.

[2] Marc Milner. Canada’s Navy: The First Century, (2nd ed ed. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2010) 36.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Gilbert Norman Tucker, “The Career of the H.M.C.S. Rainbow,” British Columbia Historical Quarterly, Vol. 3, No. 1, 1943. 13.

[5] Archer Fortescue Duguid, Official History of the Canadian Forces in the Great War, 1914-1919. General Series Vol. I, from the Outbreak of War to the Formation of the Canadian Corps, August 1914-September 1915, (Ottawa: J.O. Patenaude, printer to the King, 1938) 14.

[6] Ibid, 14.

[7] Ibid, 10.

[8] Ibid, 12.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Admiral Patrick Brock, “Rainbow 1891-1910,” in the Brock Files, Original documents in Maritime Museum of British Columbia, Victoria B.C. n.p.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Tucker, “The Career of the H.M.C.S. Rainbow,” 15.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Duguid, 25.

[15] Tucker, 15.

[16] Milner, 39.

[17] Tucker, 16.

[18] Brock, n.p.

[19] Ibid, 16.

[20] Brock, n.p.

[21] Tucker, “The Career of the H.M.C.S. Rainbow,” 16.

[22] Ibid.

[23] Duguid, 25.

[24] Ibid.

[25] Milner, 40.

[26] Ibid.

[27] Ibid.

[28] Tucker, “The Career of the H.M.C.S. Rainbow,” 16.

[29] Milner, 41.

[30] Tucker, “The Career of the H.M.C.S. Rainbow,” 16.

[31] Milner, 42.

[32] Ibid

[33] Ibid.

[34] Ibid.

[35] Ibid.

[36] Brock, n.p.

[37] Milner, 40.

[38] Brock, n.p.

[39] Ibid.

[40] Duguid, 26.

[41] Brock, n.p.

[42] Brock, n.p.

[43] Ibid.

[44] Milner, 40.

[45] Ibid.

[46] Tucker,

[47] Brock, n.p.

[48] Milner, 43.

[49] Gilbert Norman Tucker, The Naval Service of Canada: Its Official History, (Ottawa: King’s Printer, 1952), 280.

[50] Ibid.

[51] Ibid.

[52] Ibid, 280.

[53] Ibid.

[54] Brock, n.p.

[55] Ibid.

[56] Ibid.

[57] Ibid

[58] Ibid.