The Hindu Nationalist government of Narendra Modi, with unexpected suddenness, has abolished the special constitutional status of the Muslim-majority state of Jammu and Kashmir (J&K).

On Aug. 8, Prime Minister Modi, in a speech to the nation, described the new era that has dawned. He said with the abolition of special status, all citizens of India were now equal. He said the citizens of Jammu and Kashmir could now see enhanced economic and social development, previously hampered by its special status. A new era, he said — a “New India” — has been ushered in.

But this is an era of ethnic majoritarianism that erases differences, dissent and the rights of minorities. Uniformity has become the defining feature of the Indian state, replacing the carefully constructed federal asymmetry and multicultural democracy.

Modi introduced his presidential order to Indian Parliament, where his Bhartiya Janata Party (BJP) has an overwhelming majority. The two resolutions passed.

The first revoked Article 370 and the second demoted the state by splitting it into two union territories: Jammu and Kashmir (with a legislature) and Ladakh (without a legislature). All this was done without any prior consultation, either with the elected representatives of the Indian Parliament or the people of Jammu and Kashmir. More than 35,000 additional central forces personnel were deployed in the Kashmir Valley.

Hindu pilgrims, tourists and non-Kashmiri students were asked to return home. All educational institutions have been closed. Some 300 local leaders and all major political figures (including former chief ministers Omar Abdullah and Mehbooba Mufti) have been either put under house arrest or held in government jails. The valley remains under a drastic curfew and with no internet connectivity.

In correcting what it considers the mistakes of Indian post-partition history, Modi’s government has undermined India’s democracy. It has erased the innovative federal constitutional design that had brought forward a reconciliation of differences and similarities in one nation.

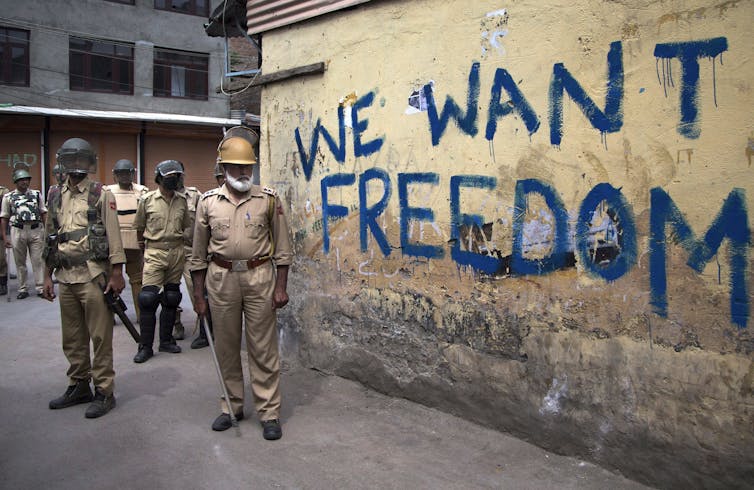

This August 2016 photo shows Indian policemen during a curfew in Srinagar, Indian-controlled Kashmir. (AP Photo/Dar Yasin)

This August 2016 photo shows Indian policemen during a curfew in Srinagar, Indian-controlled Kashmir. (AP Photo/Dar Yasin)

Background of the current Kashmir crisis

The genesis of the special status goes back to 1947 when, after Indian independence, the princely state of Jammu and Kashmir was integrated into the Indian state. As a result of the tribal invasion from Pakistan, the maharaja of Kashmir signed a Treaty of Accession with India.

India stipulated that, once the state had been freed of tribal invaders, its people would decide their future political association.

This set in motion a whole train of events that have fuelled the seemingly unending turmoil in the Kashmir Valley, namely: the arrival of the Indian army in the state.

This led to the state’s partition into the India-administered state of Jammu and Kashmir and Pakistan-administered Kashmir (called Azad Kashmir). In January 1948, India complained to the United Nations Security Council about Pakistani aggression and the following year, in January 1949, the UN Commission for India and Pakistan (UNCIP) passed a resolution asserting the disputed nature of the state and confirming the right of self-determination — which remains unfilled till this day.

The result of this complex history are the irreconcilable positions taken by India (Kashmir as an integral part of India) and Pakistan (Kashmir as a disputed territory); and Articles 370 and 35A which legally establish the Indian-administered Jammu and Kashmir’s asymmetric constitutional relationship with India.

For the last seven decades, Articles 370 and 35A have determined Jammu and Kashmir’s unique political relationship with the Indian state. It is the only state in India to have its own constitution. It kept its internal autonomy intact except for defence, communication and foreign affairs.

Its cultural identity was to be maintained by restricting the right to property and employment to only Kashmiri permanent residents. Over the years, there has been an incremental abrogation of the special status. But what had remained intact were the citizenship rights regarding property ownership and public employment.

For more than 20 years, the predominately Muslim Kashmir Valley has been engulfed in a secessionist movement to demand azadi (freedom) from the Indian state. Pakistan supports the movement, and homegrown militancy has been steadily on the rise.

The essence of Kashmiri Muslims’ discontent can be captured under three headings: a perceived threat to their agency over the control of their territory (apprehensions within certain quarters about the State’s accession to India); fear and anxiety of losing their religious identity; and disappointment with the governance agenda.

Minority rights have shrunk

The Modi government, in ushering a new era of “one nation (read Hindu), one India,” has completely misunderstood the original intent of the special provisions for Jammu and Kashmir. Through Articles 370 and 35A, the Indian state-recognized differences in the cultural and political identity of the Kashmiri population, while the similarities between Kashmir and the Indian state rested on democratic rights and principles.

No doubt this historical entente has seen ruptures over the last seven decades. Yet multicultural democratic India was to remain the national symbol. Sadly, recent government actions have replaced it with Hindu majoritarianism.

The space for minorities, particularly Muslims and the tribal population in northeast India, has shrunk. Outside Jammu and Kashmir, Article 371, which gives constitutional and legal status and powers to those tribal communities in acknowledgment of their distinct culture and practices, also appears to be in jeopardy.

If the BJP can undo a complex set of legal and constitutional mechanisms, the same can be done to the northeast’s special powers, but with greater ease.The Kashmir Valley, although at present under complete lockdown, is quiet.

But its resistance is deep. It’s a place where past events and collective memory play significant roles, never quite effacing what came before. The events of Aug. 5, 2019, will be added to the memory of Kashmir Muslims. It will join other dates:

- July 13 Martyrs Day (21 Kashmiris killed in 1931 outside the Srinagar Central jail by the troops of the Dogra Maharaja);

- Oct. 27 Occupation Day (the signing of the Accession Treaty);

- Feb. 11, Feb. 19 and July 6 Martyrdom Anniversaries of all those who have openly challenged the India state;

- Feb. 11 in 1984, Maqbool Butt hanged; (founder of the Kashmir liberation movement in 1964);

- Feb. 9, 2013 Afzal Guru hanged; (convicted of his role in the bombing of Indian Parliament in 2001);

- July 2016; Burhan Wani killing (22-year-old homegrown militant and commander of the Hizbul Mujahideen).

Kashmiri Muslims have, for more than seven decades, been proactive in seeking to guard their special status and their collective identity. The consequences of all this cannot be anything but the increasing alienation of the valley’s Muslims and their deepening distrust of the Indian democracy, further reinforcing Hindu/Muslim fault lines and Kashmiri demand for azadi.

This piece was first published on the theconversation.com