South Africa seems set to amend its Constitution to allow land expropriation without compensation. On 27 February 2018, the governing African National Congress (ANC) supported a measure proposed by a small, ‘left-wing’ opposition party, the Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF), to amend the Constitution to allow for land expropriation without compensation. This initial vote left many people in South Africa and abroad worried that, by supporting the EFF measure, the ANC was signalling its intention to adopt the EFF’s plan to nationalise all land, and feared that a Zimbabwe-style land seizure process would follow. Where the ANC has long been the champion of the Constitution and its Bill of Rights, since the EFF was established, Malema (the party’s leader) has argued that the Constitution is an impediment to radical transformation and needs to be drastically altered, if not completely abandoned. Thus, the ANC’s willingness to vote with the EFF to amend the Constitution to allow land expropriation without compensation also stoked fears of a wider assault on the Constitution.

Domestic and international concerns have not led the ANC to retreat from its support for the EFF’s call for constitutional changes. After the vote passed in the National Assembly, President Ramaphosa ordered a Parliamentary Review Committee to review how the Constitution would need to be changed in order to allow for land expropriation without compensation, and on July 31st he announced: “It has become patently clear that our people want the Constitution to be more explicit about expropriation of land without compensation, as demonstrated in public hearing.” Since this announcement, much of the news coverage has fixated on the potential or threat of undertaking such a policy, and the need for land redistribution in a country often described as ‘ready to explode,’ while questions of constitutionalism have been relegated to the background. However, in the same speech, Ramaphosa stated, “The ANC reaffirms its position that the Constitution is a mandate for radical transformation both of society and the economy.” Drawing on this statement, this post will explore how changing the Bill of Rights to allow for land expropriation without compensation does more to serve the Constitution than to mar it.

In short, there is nothing to suggest that South Africa’s land expropriation will spiral into a violent and problematic process of land seizures fuelled by corruption and political instability, as was the case in Zimbabwe. Constitutional reform is needed, as is more radical land reform, and both are possible and necessary and in keeping with the Constitution itself.

The Bill of Rights

South Africa’s Constitution includes a robust Bill of Rights, often called the most progressive in the world. It offers protections based on: “race, gender, sex, pregnancy, martial status, ethnic or social origin, colour, sexual orientation, age, disability, religion, conscience, belief, culture, language and birth”. Additionally, Section 25 of the Bill of Rights contains the provisions for the protection of private property and explicitly protects property owners from expropriation without compensation. Specifically, Section 25.2 allows for land expropriation for “a public purpose or in the public interest” but it also explicitly requires compensation and Section 25.3 states that compensation must be just and equitable. Ramaphosa’s comments seemingly mark a willingness to explore amending this section of the Bill of Rights to make more explicit the ability of the state to expropriate land without compensation. If Section 25 is altered, it will be the first time the Bill of Rights will have been revised since the final (new, post-apartheid) Constitution was accepted in 1996.

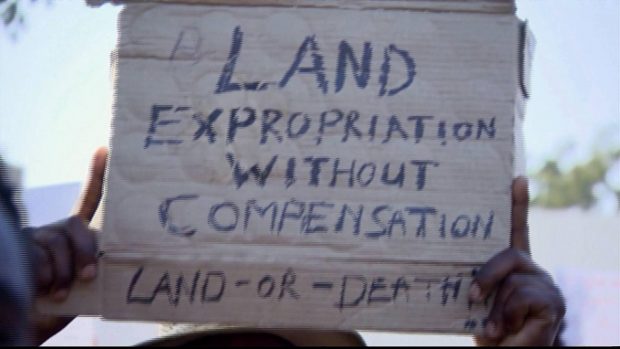

Photo Credit: REUTERS/Mike Hutchings

In March, Deputy Minister of Public Works, Jeremy Cronin warned against introducing changes to the Bill of Rights, stating: “Don’t change the Bill of Rights, because don’t forget the Bill of Rights has a higher order of importance than the rest of the Constitution. We have changed other elements of the Constitution but we have never changed the Bill of Rights. It is the foundational social compact of 1996.” He is not alone in this view. Indeed, this perspective that the Bill of Rights is untouchable pervades much political debate and commentary in South Africa. Many prominent political actors, including the ANC MP in charge of the Parliamentary Review Committee and land reform activists, have argued that as it currently stands, Section 25, allows for some degree of land expropriation without compensation, particularly in cases where the land has been abandoned and/or sits idle. While debates occur about whether or not expropriation without compensation is constitutionally permissible, what is clear is that there is an urgent need for comprehensive land reform. Looking closer at Cronin’s description of the Bill of Rights as “…the foundation social compact of 1996,” demonstrates the exact reason why Section 25 must be changed to allow the state to expropriate land without compensation. Only by doing so will South Africa be able to achieve the Bill of Rights’ promise that it: “is a cornerstone of democracy in South Africa. It enshrines the rights of all people in our country and affirms the democratic values of human dignity, equality and freedom.” Certainly, current land ownership patterns, which are largely unchanged from the apartheid era – ‘white commercial agricultural land’ accounts for 67% of South Africa’s land mass, while just 15% is allocated for ‘black communal areas’ – are a major impediment to South Africa’s quest for equality, freedom, and human dignity for all.

South Africa’s Constitution is the product of the political negotiations that brought an end to apartheid and ushered in democratic rule and President Ramaphosa was a key architect of the constitutional settlement. As he told a South African radio show in 2016, the constitutional negotiations were about “finding solutions for the country” and getting past the “political log jam the country was in”. In the final years of apartheid, the stalemate between the armed resistance and the apartheid government left the country in a state of chaos (with fighting so intense and widespread in Natal that many refer to it as a civil war) and prolonged economic decline, which opened the door for negotiated political reform. South Africa’s Constitution needs to be understood as a product of this political compromise, and as a main architect of the constitutional settlement, Ramaphosa understands this more than most. But, what he also understands is that South Africa’s constitutional settlement, and particularly the Bill of Rights, was drafted to provide the pathway for South Africa’s transformation from its apartheid past. Indeed, it was crafted in a manner that accepts that the past will not be easily forgotten or overcome and sets the terms for transformation by advancing human rights to repair apartheid era injustices, particularly to confront those injustices, such as land ownership, that carried over into democratic South Africa. Therefore, as I show below, reforming the Bill of Rights by removing an impediment to transformation would enable the state to better achieve the Bill’s ultimate purpose.

Changing Section 25: Threat or Adherence to the Bill of Rights?

Photo Credit: Al-Jazeera

South African legal scholars often argue the Bill of Rights provides the blueprint for transformation by placing an affirmative duty on the state to take steps to implement its progressive measures, such as the right to food, water, and housing. Even Section 25 provides that the protection of private property shall not “…impede the state from taking legislative and other measures to achieve land, water and related reform, in order to redress the results of past racial discrimination…” and that property may be expropriated in the public interest, which includes, “…the nation’s commitment to land reform, and to reforms to bring about equitable access to all South Africa’s natural resources[…].” Thus, the private property protections are already subject to limitations that demonstrate the compromise agreed to first in 1993 and reiterated in the final Constitution in 1996. There is a tension in Section 25 whereby the state must protect private property from expropriation without compensation (which serves to reproduce colonial and apartheid era land distribution), while also striving to redress the legacies of colonial and apartheid era land policies. To resolve this tension, Section 25 must be reviewed. Only by revising Section 25 to allow land expropriation without compensation will South Africa be able to undertake comprehensive land reform required to redress legacies of colonial and apartheid land policy, which still greatly privilege the white minority.

Despite the Bill of Rights’ promise of transformation, nearly 25 years on from South Africa’s first democratic election, access to land remains rooted in the colonial and apartheid policies of the past with little meaningful redistribution completed. While it is true that the government could have done much more in terms of land redistribution within the present constitutional framework, it is also undeniable that the constitutional protection of private property has slowed meaningful transformation when it comes to land redistribution. The government’s interpretation of Section 25 has been to take a “willing seller, willing buyer” approach that has limited its ability to gain access to land for redistribution by providing the titleholder with ultimate power in the negotiations. In cases where an agreement cannot be reached, a court must assess if the compensation offered by the state is just, which draws out an already lengthy process. Allowing for a streamlined process for land expropriation without compensation could allow the state to move more quickly to redistribute land and at a much lower cost. South Africa needs comprehensive land reform not only to redress legacies of racialized land distribution, but land reform also has the potential to accelerate the provision of a variety of the Bill of Rights’ promises. It has the potential to contribute to local economic development, food security and to advance human dignity, equality and freedom as imagined in the Constitution. Indeed, meaningful access to land, particularly agricultural land, can be a major contributor to reducing poverty, improving health outcomes, and empowering individuals and communities.

As noted in the introduction, some in South Africa worry that permitting land expropriation without compensation will cause South Africa to follow a Zimbabwean model of land seizure; Malema and the EFF have stoked these fears with their calls for nationalisation of all land, and their eagerness to point to Zimbabwe as a model. However, there is little reason to believe this is the ANC’s intention because this would require greater changes to the Constitution than the government is considering. Nor is there any evidence to suggest such reforms would result in the type of violent and problematic process that unfolded in Zimbabwe. As Ramaphosa described, “The intention of the proposed amendment is to promote redress, advance economic development, increase agricultural production and food security.” Based on the work of the Parliamentary Review Committee, Deputy Minister Cronin, who initially stated that the Bill of Rights should not be changed, is currently drafting legislation that would outline the steps required for land expropriation without compensation and details the type of land that the state would be able to target for expropriation. This legislation, which would take effect once the constitutional amendment is complete, would limit the use of expropriation without compensation to abandoned, unused, or underused, land, buildings and commercial property. In so doing, the proposed legislation would either encourage title owners to use their property better, or it would allow the state to take control and redistribute the land to those in need. It also makes provisions that the state must provide access to the resources, such as money, tools, soil, seeds and water, required by those provided land to use it effectively.

Only time will tell, but it appears that once the Constitution is amended, redistribution of land that was expropriated without compensation will help to redress the conditions of landlessness that colonialism and apartheid entrenched.

As Malema keeps reminding South Africans: “It is not unconstitutional to change the Constitution.” And, while he would favour a complete overhaul of Section 25 to allow for nationalisation of all land in South Africa, what Ramaphosa seems to be signalling is a much more measured revision to address the incongruence between the property protection and the transformative purpose of the Bill of Rights. Indeed, Ramaphosa and the ANC are seeking to limit the changes to allow the state to fulfil the Constitution’s promise of transformation. To protect all land from expropriation without compensation runs counter to the overarching goals of the Constitution and the Bill of Rights. Consequently, revising this section to provide greater clarity as to when the state can expropriate land without compensation would allow for greater adherence to the ultimate purpose of the Constitution. Thus, by amending Section 25 of the Bill of Rights, Ramaphosa and the ANC are doing more to adhere to the Constitution than they would by refusing to amend it out of a reverence for the Bill of Rights.

Janice Dowson is a PhD Candidate in the Department of Political Science at the University of Victoria. She can be reached at jdowson@uvic.ca. Thanks to Regan Burles and Marlea Clarke for their helpful comments on an earlier draft.