The Russian study-abroad program in St. Petersburg, a partnership between Dalhousie University and St. Petersburg State University, offers Canadian university students a unique and rewarding experience in the cultural capital of Russia. This reputation is a product of its rich history, proximity to Europe, and preeminence in the art world. For this intensive Russian program, two months are spent with a homestay while attending classes four days per week. By the end of the program, students complete 160 hours of classwork and earn a certificate. I would recommend to those interested in this program to take at least two years of Russian before attending. This is not due to the difficulty of the courses, since the school groups students by fluency, but because of the level of interaction students will experience with Russian citizens and their homestays. For those who are already multilingual and quick to pick up languages, only one year of Russian may be required. This was the case for at least three students who attended the program this past Summer. Finishing my third year at UVic and armed with two years of Russian, I was only prepared for very basic conversation once I arrived. But after a few weeks of being bombarded with the cryptic sounds of the Slavic tongue, my Broca’s area began showing signs of activity. My Russian is still far from fluency, but the program led to much needed improvement in my conversational skills and comprehension.

Arriving in St. Petersburg in the middle of May, which happened to be during a heat-wave, my first introduction to the country was a broken jetway at our arrival gate. Passengers on the plane had to disembark onto the tarmac and wait for buses for a ride to another entrance. I thought it was a pretty comical welcoming, and it seemed to foretell of future absurdities on my trip. After making it through customs, students were met at the Poltovo Airport with a university shuttle-bus, and whisked off to their respective home-stays. I was paired with a student from Calgary, and housed relatively close to the institute. My room mate and I stayed with an old babushka who lived on the top floor of an apartment complex. It is located in the north-eastern part of the main island, on Starorusskaya Street, 30 minutes by foot to the school. We had the weekend to get settled in before classes started the following Monday. I was given a sizable room, equipped with a desk, TV, and a bizarre little bed that looked like a fold-out couch. For the most part, the amenities of the apartment met my needs. I was especially pleased with my view across the city, which included St. Isaac’s Cathedral and Kazan Cathedral in the distance. Not having air conditioning, nightly visits by mosquitoes, and losing hot water for a few weeks proved uncomfortable, but I was able to adapt. This meant using a plug-in fumigator, heating a pot on the stove for shower purposes, and cold water foot baths. Since tap-water is not potable, students also have to rely on water jugs bought from the store. Although this is slightly inconvenient, it is helpful that the 5L jugs can be purchased for under a $1.50.

The majority of foreign visitors to St. Petersburg arrive with little-to-zero knowledge of Russian, relying on guides and planned excursions to venture around the city. I feel like this type of travel really detracts from experiencing the culture, and I enjoyed being able to navigate the city independently. Another reason to learn Russian before visiting is that it allows you to connect with locals. Although the younger generations are more likely to know English, it is not as common as you would expect. As I observed, locals generally prefer to hear you speak broken Russian than rely on your native language. In fact, on a few occasions strangers approached our Canadian group, while we chatted away in English, and demanded that we speak Russian. It was mostly in jest, but it made me aware of another peculiar Russian trait, which is the lack of inhibition that Russians have in expressing themselves publicly. In particular I am reminded of the intense public displays of affection between couples on the streets and metro. In Canada they would be sure to raise some eyebrows, but that’s not the case in Russia. Russians also seem to have a level of familiarity with strangers that is not seen in Canadian cities. There was a certain vibe in the city that I cannot exactly pinpoint, but if I were to clumsily describe it, I would say it is a feeling of cohesiveness and shared understanding. In such a culturally and ethnically homogenous environment, I think this may be a natural byproduct.

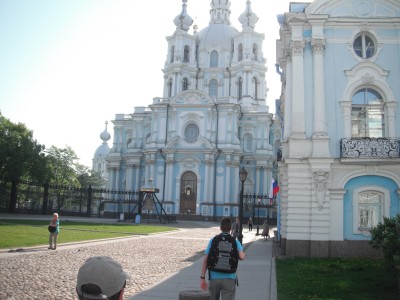

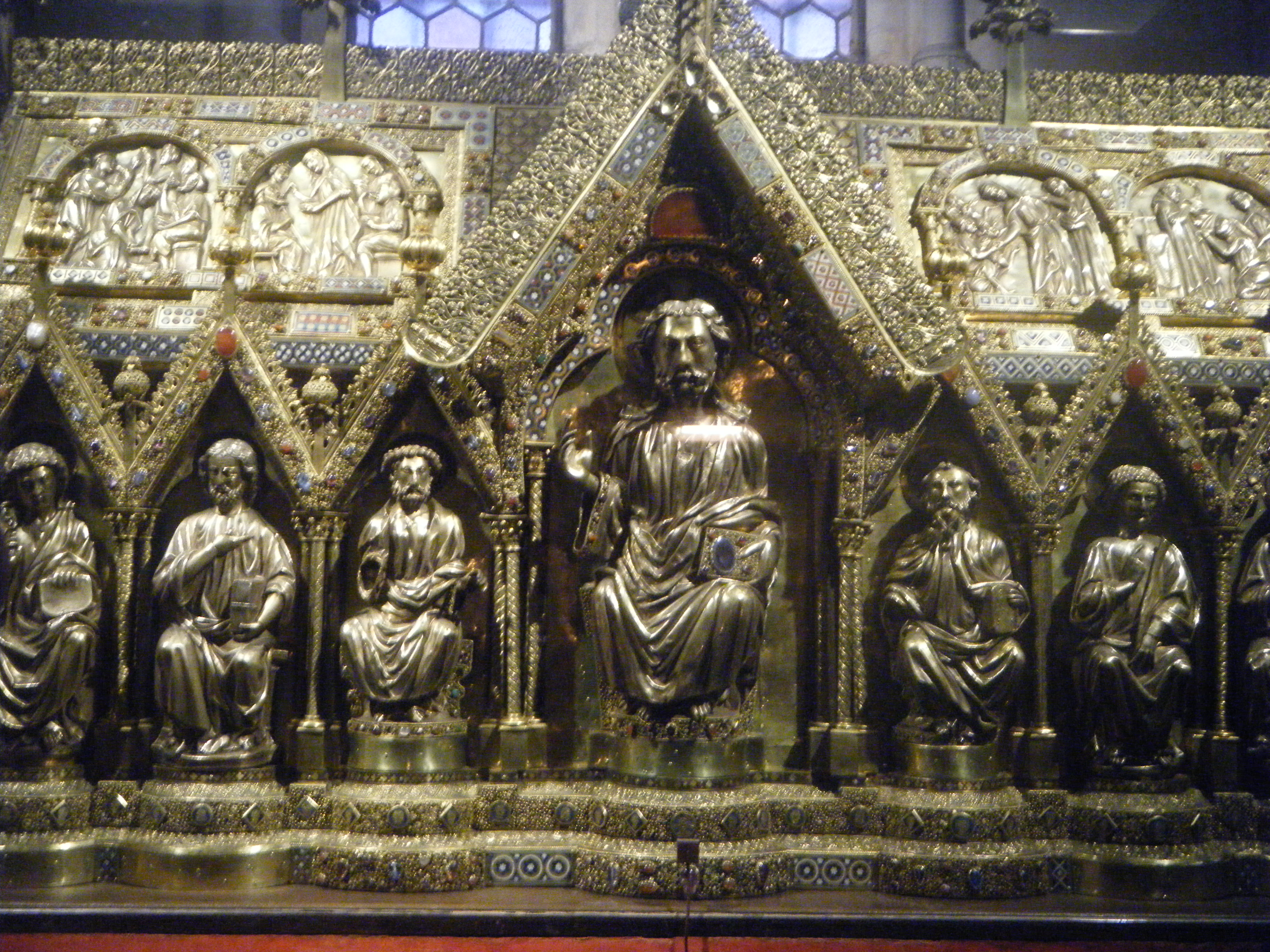

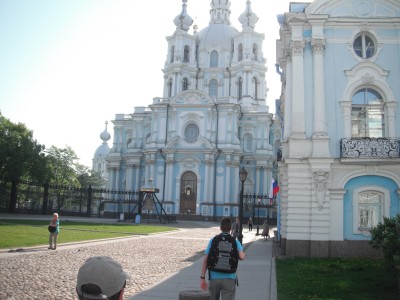

I found the two-month stay in St. Petersburg to be an ideal amount of time to take in the sights of the city, including its festivals, museums, performances, beautiful architecture and countless historic sites. Some of my favourite tourist sites included the Hermitage, the Russian Museum, the War Museum, Petergof, Pushkin’s Museum, Peter and Paul Fortress, and the Summer Garden. The program also overlaps with the ‘White Nights’ season in St. Petersburg, a time when the sun never seems to sink under the horizon and its possible to stay out all night (although sometimes this is unavoidable, especially if the bridges go up, leaving you stranded on one island until the early hours of the next morning). Near the end of my trip I got to visit Moscow for the weekend, where I travelled by train with a friend. Moscow was one of the highlights of my trip, and I would highly recommend it. There is a completely different feel to Moscow, and a trip to Russia cannot be complete without seeing it once. Unfortunately, I did not make it to the Mariinsky Theatre (or the Bolshoi) to watch a showing, but I heard great things from other students. My homestay babushka actually sold tickets to the Mariinsky, and even visited Smolny one-a-week to sell them to students, so I think I may have disappointed her by refusing. So if you happen to see her there (she goes on Wednesdays and sets up a stand), tell her “Yan is sorry” (Yan is my Russian name).

Since you’re essentially on your own when participating in this program, you’re responsible for feeding yourself (among other things). There is a lunch cafeteria in the school itself, but it serves a small variety of food that is of mediocre quality. I found this surprising because the Smolny campus itself is spectacular. Consequently, I decided on bringing my own food to avoid the cafeteria early on in the trip. As a large city, St. Petersburg has plenty of places where you can find good food. If you’re on a tight budget, it’s best to prepare some meals yourself. Our hostess allowed us full access to the kitchen, and cooked us breakfast every day. In Russian cities, the corner stores, or “Produktiy“, function as small grocery stores where you can find most basic goods. There are a few larger grocery stores, such as in the Galleria, a large shopping mall off Nevsky, and Stockmann’s mall, also off Nevsky, which offer better selection. In Russia, it is also quite common to find Stolovayas, which are simple cafeteria restaurants that offer various types of Russian cuisine. These places are always cheap, and are a good option if you’re on the go. One thing that is uncommon to eat in Russia is peanut butter, and comes at a pretty steep cost if you can find it. I couldn’t bring myself to pay 350 rubles for a small jar of peanut butter, however, despite the temptation. Coffee is also surprisingly unpopular in Russia, with the majority of people preferring tea. I admit to be one with a coffee addiction, and so the lack of a coffee-maker in the apartment was pretty enervating.

As for public transportation in St. Petersburg, it is extensive, cheap and convenient. It includes five metro lines, two train stations, a bus system and taxis. The subway system in St. Petersburg is one of the most impressive features of the city. In the grand halls of the city’s many metro stations, serving over 2 million passengers daily, one can experience the famously long escalator rides (St. Petersburg is home to the deepest metro on Earth) and observe the radiant Soviet-era adornments. My favorite station was Avtovo, which is built with ornamented glass columns and beautiful white marble. If you’re traveling to Petergof, Avtovo is the station where ‘Marshrutkas’ (think ‘airporter’) pick up passengers and drop them off. This is the cheapest method of travel to Petergof (costing 60 roubles) – the other popular option is a ride by ferry. Be careful to avoid the gypsy cabs, especially at night, since they are notorious for victimizing tourists.

Since the Summer of 2014 marked a fairly uncongenial time between the West and Russia, I was unsure of how I would be received as a Westerner. As I discovered, daily life in Russia was proceeding with little regard to geopolitics. Although the director from Dalhousie advised us to be very cautious when discussing events on the Ukraine, especially in public, I was never put in any difficult situations. As a side note – I did bring up politics with my home-stay grandmother over breakfast one morning. It was interesting to hear her opinion on Russia’s history (incuding many harsh words for Gorbachev), but as it would often happen with our conversations about politics, she began to despair over the horrors of WWII. With my Russian being too limited to absorb everything, I can only remember snippets, such as her proclaiming that “All the good men were lost in the war”, which she blamed for the difficult years that followed. Even as World War II becomes a more distant memory for most of us, the event continues to be a source of tremendous pride for the Russian people, and is commemorated every year on May 9th, also known as Victory Day. Although this comes before the Summer language program, there are other opportunities to witness Russian patriotism, such as on St. Petersburg’s anniversary (the Day of Peter the Great), the Scarlet Sails festival, and Children’s Day.

If you’re interested in what type of clothing you should bring to St. Petersburg, I would recommend a business casual look. In Russia, it seems women are especially concerned with how they present themselves, and their standard of dress is considerably higher than in Canadian cities. High-heels are almost ubiquitous, and I imagine also very uncomfortable. As one of our tutors explained, St. Petersburg residents often spend the majority of their earnings on their appearance, even if that means less money to spend on food. For men, it is typical to wear a leather jacket (unless it is sweltering), slacks, and dress-shoes. For older men, the standard of attire means sandals and shorts are frowned upon. I rarely saw any locals in shorts, except maybe young boys. This may seem like a dilemma for those who enjoy wearing shorts, but as a tourist (and believe me, you won’t be able to disguise your foreign origins) you don’t really need to abide by these rules. So what you wear is not that important, but if you’re worried about standing out, it is always better to adopt the local style. In the case of one male student from Calgary, who decided to wear a gold-cross necklace (despite being a professed atheist), a newly purchased leather jacket, slacks and slip-on leather shoes, you might say that’s worrying a little too much.

I’ve tried to paint a general picture of what it is like living in St. Petersburg, including what can be expected as a visitor to the city. Although this study-abroad program comes with its challenges, I found it to be very rewarding and worthwhile. The memories I made in St. Petersburg will be with me for life, and I feel very privileged to have seen some of Russia firsthand. It has also encouraged me to continue working towards better Russian comprehension, as well as eventually earn a masters in Russian studies. I believe the world needs more people with an understanding of Russia and the nation it represents. St. Petersburg’s Summer program at the Federal State Educational Institute of Higher Professional Education, St. Petersburg State University, has a solid track-record as an institution providing academic and international experience for those who visit St. Petersburg.