UVic’s Recycling Failure & Group Mentality

When we set out to explore waste sorting at the University of Victoria (UVic), we expected to find that UVic students and others at the University practice sorting quite well. The UVic website on sustainability even claims, “Over 75% of waste produced everyday at the UVic campus is diverted from the landfill through innovative recycling and composting initiatives”. However, our research shows that waste sorting at UVic is far worse than we guessed.

Image 1. The garbage bin we collected from. Source: Paige McLachlan

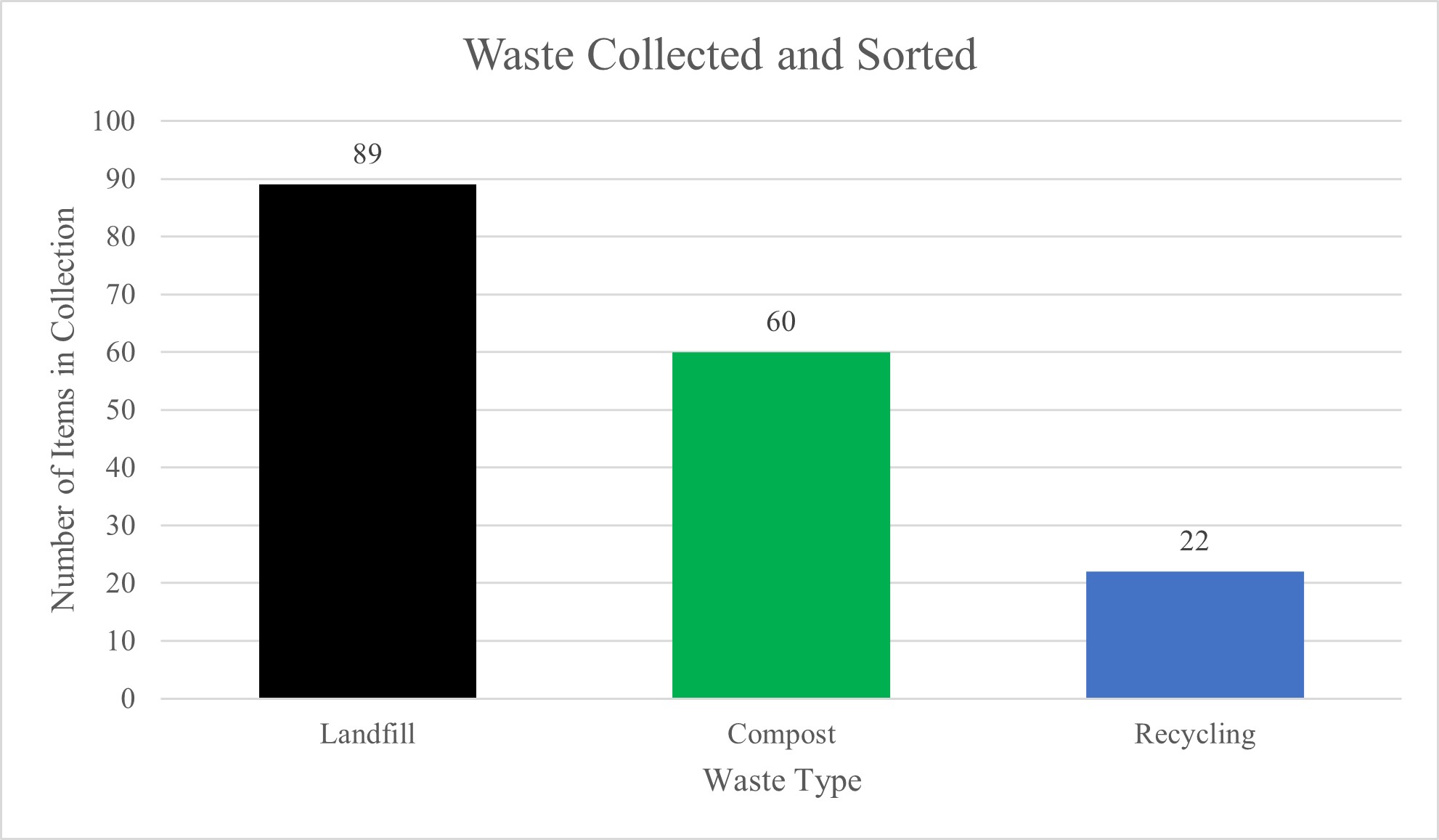

We collected 171 pieces of waste from a garbage bin on campus (Image 1) on September 24th, 2021, and sorted them based on the University of Victoria’s sorting guidelines. Of these pieces of waste, a shocking 82 (48%) of them did not belong in the landfill. As shown in Figure one (below), 60 items were compostable, and 22 were recyclable. If UVic’s claims are true, why is there such poor waste sorting? Roughly 26% of the improperly sorted items that we collected were paper plates, chip bags, and potato chips, suggesting that the garbage bin may have been present for an event. Based on the possibility of an event, we initially theorized that group mentality might be partially responsible

Figure 1. Waste collected and sorted

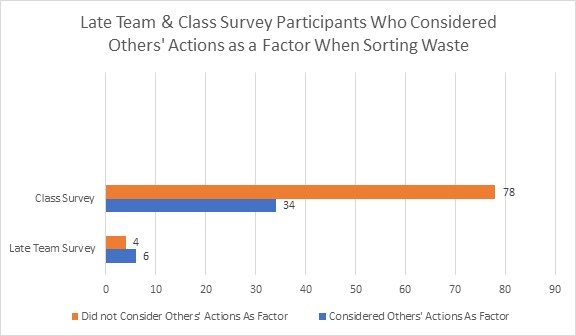

We explored the potential group mentality effect on waste sorting practices using an ethnographic survey. The survey was done by the entire Anthropology 392 class and interviewed 128 people on the UVic campus. The survey was quite broad, as it was designed by a class separated into 14 different groups. One question in particular was relevant to group mentality, asking what factors the participants consider when sorting waste, with one of the options being what other people are doing (others’ actions). As shown in the chart below (Figure 2), a mere 34 of the 112 people interviewed by the class said that they considered others’ actions as a factor when sorting waste.

Figure 2. Survey Participants Who Consider Others’ Actions as a Waste Sorting Factor

The low portion of participants (30.3%) who considered others’ actions as a factor when sorting waste seems peculiar. Indeed, it does not match up with contemporary research such as a study done by Zhang and others (2017) which found that 91% of the college students they interviewed would sort waste if their friends did. Another study, done by Hao and others (2020) found that 88% of the college students they interviewed would separate waste if the people around them did.

So why did our survey have such drastically different responses? One possibility is that more than just students were interviewed, but even with others removed, only 34.5% of the students interviewed said they consider others’ actions as a factor when sorting, so that possibility is ruled out. Cultural differences may have an influence, but likely wouldn’t account for the nearly 60% difference in responses. We suggest that the most likely cause is in the phrasing of the survey question. Our survey posed “what other people are doing” as a factor in sorting. The language used by Zhang, which mentioned friends, and the language used by Hao, which mentioned people around them, both suggest a group relation. We used the term “other people”, which may have suggested there was no relation between the participants and the “other people”. Despite the difference, over a third of students considering others’ actions as a factor when sorting is still notable.

Our collection of garbage made it quite obvious that most people are not sorting their waste properly. With over a third of interviewed students stating that what other people are doing is a factor in their sorting decisions, it becomes clear that group mentality has a substantial influence. A more in-depth survey covering multiple scenarios with different situations, locations, and people would help us get a better understanding of exactly how and why we make these choices in regards to others. Furthermore, such a study could give extremely valuable insights into how waste sorting at universities in particular could be improved.

Universities are social environments, so social factors will naturally affect behaviour, including waste sorting behaviour. Perhaps UVic could implement a group workshop with the incentive of free coffee or lunch, which students could attend with their friends. It may also be beneficial for faculty, teaching assistants, and others at UVic that students learn from to be required to take a waste sorting workshop. If careful, accurate waste sorting is seen being done by authority figures, it is likely that the practice will spread.

References:

Hao, Mengge, Dongyong Zhang, and Stephen Morse. 2020. Waste separation behaviour of college students under a mandatory policy in China: A case study of Zhengzhou city. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17(21), https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/17/21/8190?type=check_update&version=2, accessed December 3rd, 2021

Zhang, Hua, Jiong Liu, Zong-guo Wen, and Yi-Xi Chen. 2017. College students’ municipal solid waste source separation behaviour and its influential factors: A case study in Beijing, China. Journal of Cleaner Production 164: 444–454, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.06.224 accessed December 3rd, 2021

0 Comments