Trash Realities: A Study of Waste-Sorting Habits at Bibliocafé

One of four bags of artifacts from Garbuddies’ material culture analysis.

This semester, we undertook a garbology project to determine what waste disposal looks like at the University of Victoria. We sought to answer questions about the kinds of objects being thrown away, how much waste is sorted incorrectly, and how many of those incorrectly sorted objects were thrown away together when they should have been separated. We were also interested in why people throw away the things they do, and how they decide to sort their trash.

To do this, we collected a sample of trash from the bins at Bibliocafé in McPherson Library, and surveyed staff, students, and faculty about their waste disposal habits. We sorted 230 ‘artifacts’ (pieces of trash), and as a class collected over 100 survey responses. When we compared our material culture and the survey results, we found links between the availability of bins, people’s confidence in sorting their waste, and the accuracy of their sorting.

What Did We Find?

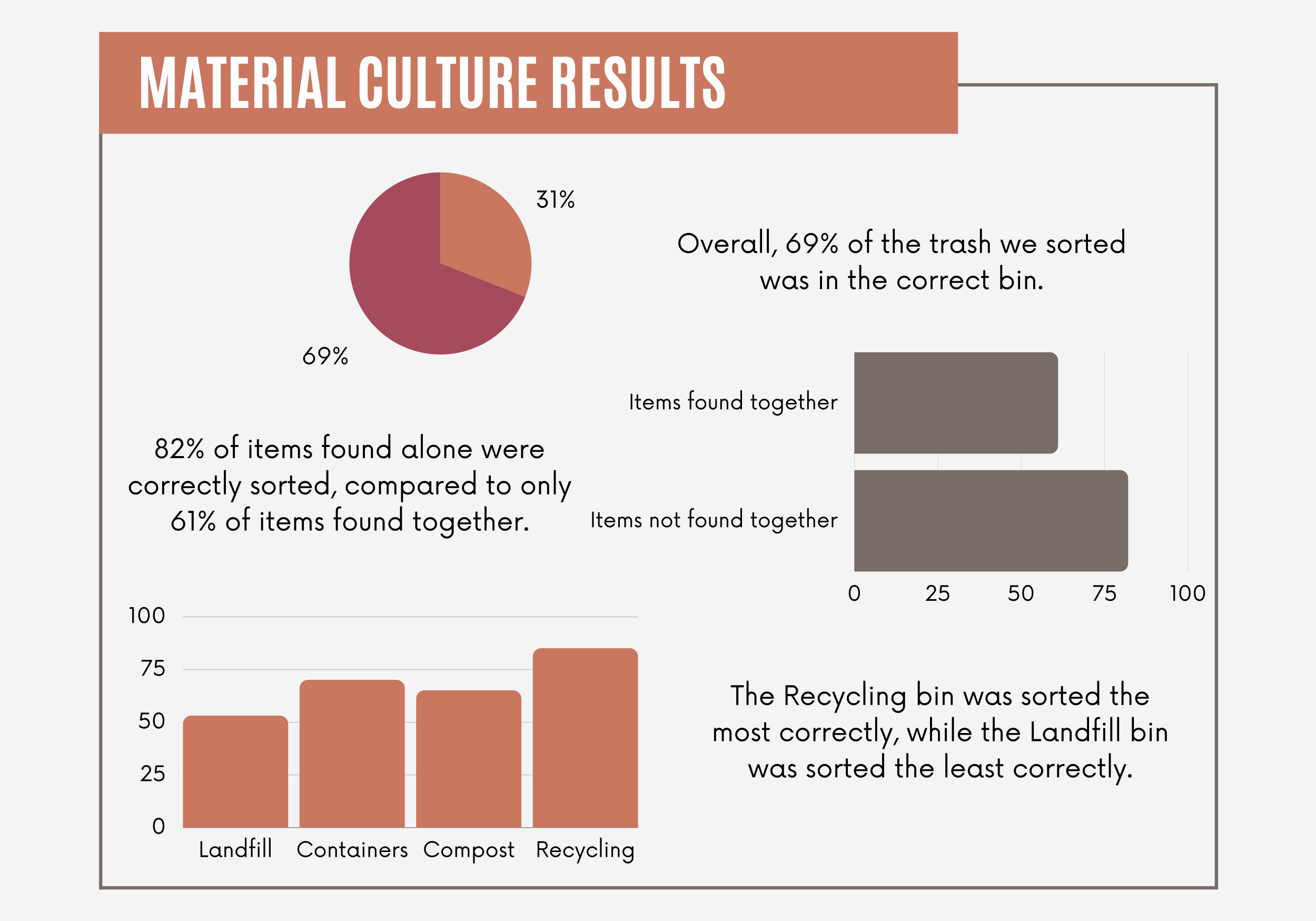

Of all the bins on campus, survey participants said there are too many landfill bins. In contrast, there are too few compost bins, especially inside buildings. This can lead to the landfill bin becoming an easy “catch-all” for trash when people either don’t know how to sort, don’t want to sort, or simply aren’t able to sort because of time constraints or bin availability. This can explain why the landfill bin we examined was sorted so poorly: only 53% of its items were sorted correctly, the lowest of all the bins we analyzed. This poor sorting could also be from an unclear Sort-It-Out policy, currently advertised online and on bin signs, with people choosing to put items in the landfill to avoid contaminating other bins.

“Only 53% of items [in the landfill] were sorted correctly”

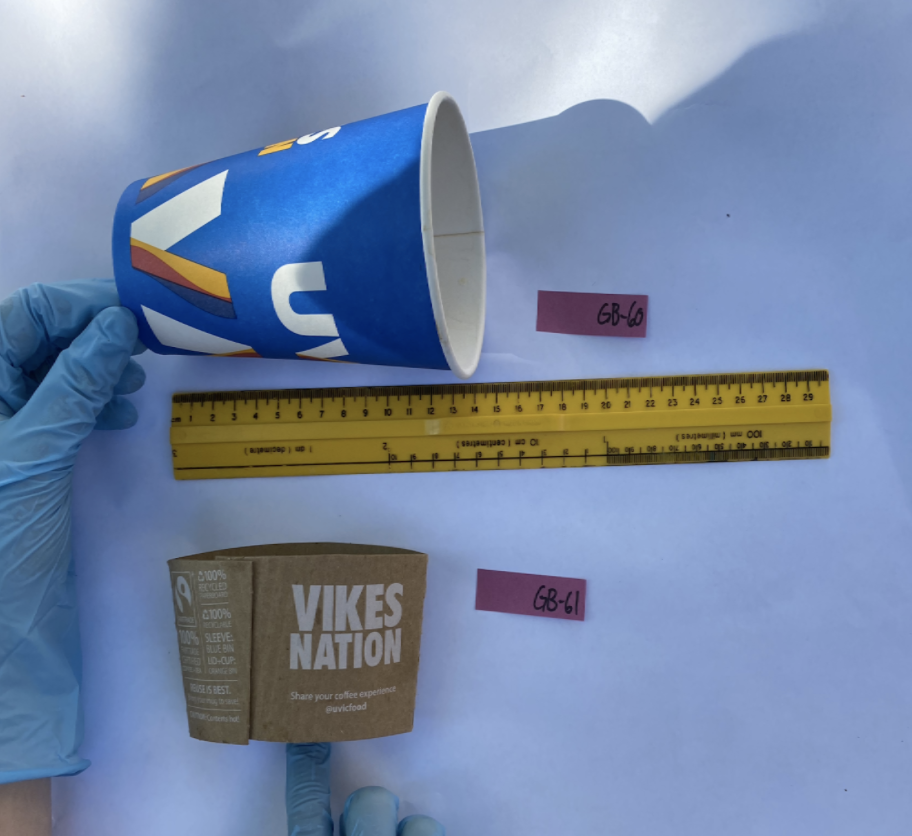

A coffee cup and its sleeve found together in the compost. They are one example of several items that were not separated and correctly sorted.

Keeping recycling bins free from contamination can significantly reduce waste sent to the landfill. For example, leftover coffee in a cup can contaminate a bin and prevent its contents from being recycled. In her TED talk, Dr. Anita Závodská, a garbologist and environmental studies professor, recommends the phrase “When in doubt, throw it out” to people unsure how to sort their waste. Yet, UVic staff, students, and faculty frequently throw out items that should be easily sorted, including items that appear on bin signs. Even staff from the Office of Planning and Campus Sustainability didn’t rate themselves as 10/10 sorters.

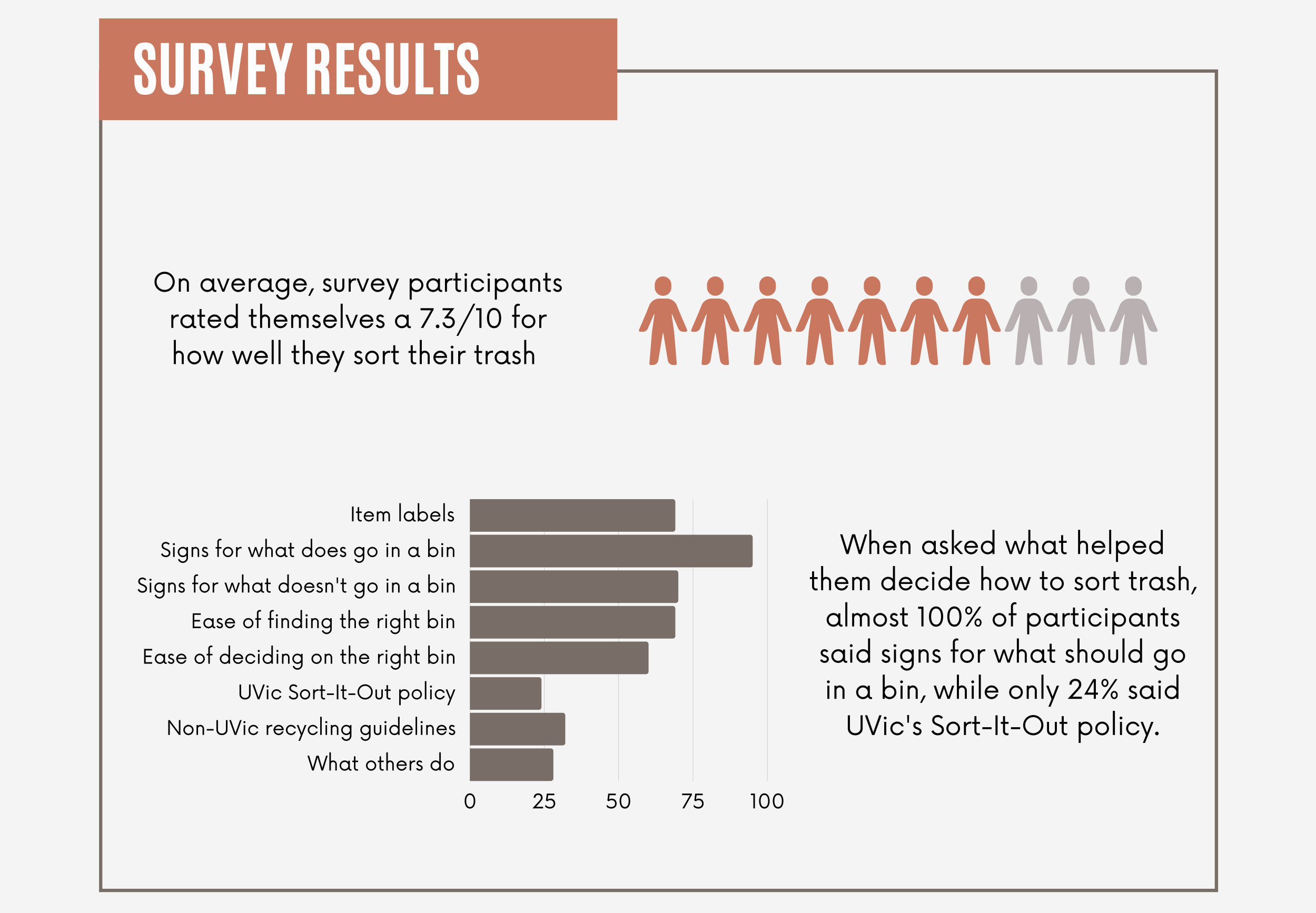

We also found that items that were thrown away together (‘in association’), instead of separated, were more likely to be sorted incorrectly. Often, one part of an item was in the correct bin, but another component wasn’t, and this contributed to the trash in our bins being sorted only 69% correctly. For example, we often found coffee cups with their paper sleeves still on thrown into the mixed containers bin. Although the cups were in the right place, the sleeves belong in the clean paper bin. Therefore, a discrepancy exists between people’s perceived sorting habits — on average, survey participants considered themselves to be sorting their garbage 73% correctly — and reality.

The most important findings from our material culture analysis.

The most important findings from our survey analysis.

How Can We Fix The Garbage Problem?

Our survey results showed that UVic’s Sort-it-Out policy is not clear enough or accessible enough to be fully successful. Over half of our survey participants weren’t even aware of the policy, despite their confidence in their sorting abilities. Better education is therefore crucial to UVic reducing the amount of waste sorted incorrectly. In addition, survey participants said bin signs with images rather than text, and the availability of relevant bins, were the most important factors in sorting their trash. It is important, then, for bin signs to prioritize pictures, and include images of items commonly found on campus rather than using stock photos. To make sorting more accessible, participants suggested clarification about the disposal of soiled packages, more education about the importance of disassembling trash, and more readily available information about waste production on campus. This could be achieved by UVic making its Sort-It-Out policy clearer and easier to find, both physically and digitally.

There is no one solution for reducing waste at UVic, but a combination of better policy education — such as trash sorting workshops during first-year orientation — QR codes on bin signs linked to UVic’s sorting policy, and strategic bin placements avoiding bottlenecked spaces can also help make a big difference.

This project shows that waste production is affected by personal actions, as well as by university policies. If you’d like to consider your own relationship to recycling further, this podcast episode provides an excellent ‘Q&A’ based on questions from Edward Humes’s book, Garbology.

0 Comments