Sorting out the Truth: Anthropologically Understanding Trash-sorting Issues on Campus.

If people spend all their time, eating, sleeping, studying and partying in one environment, there’s going to be a whole lot of trash left behind there too. Well, this mini-scale environment exists on UVic’s campus for the residents that live there full time, making it a perfect place to study people’s daily waste habits.

What does trash tell us about the waste-sorting behaviours of a UVic resident?

To find out what we could learn about how people were sorting waste on campus, my partner and I found ourselves recording the contents of the garbage bins on campus residence and asking people on campus questions about their waste-sorting experience.

Sorting some of the items in our garbage sample.

Initially, trash and people seemed to tell two different stories.

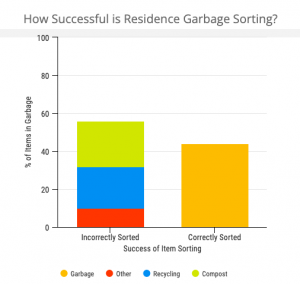

First of all, most (56%) of what was put in garbage bins on residence shouldn’t have been there. A lot of it (24%) should have been composted. Why was so much compost missorted? We sought to answer this question ethnographically— from the perspectives of people who participate in a cultural practice, like waste-sorting at UVic. Our surveys told us that it was not because people didn’t know what to compost. In fact, most people felt the most confident about their knowledge of composting. But trash can’t lie. So what was going on?

A bar graph showing the sorting data from our garbage sample.

Surveying people gave us insight that trash alone couldn’t show. Everyone said there aren’t enough compost bins on campus! Another problem? There aren’t compost bins inside residents’ rooms– and what student wants to take all the tiny pieces of mouldy orange peel out of the garbage when they take out the trash?

More to the Compost Problem than Meets the Eye?

The consensus that compost bins aren’t available enough certainly seems like part of the compost problem on campus. Paper towels, napkins, food containers, straws, the left-over coffee at the bottom of coffee cups–a lot of these things might have been composted if people had bins close by. Alternatively, people may not have perceived that all of these things were made out of compostable materials. The cornstarch straws on campus can look like plastic. Compostable take-out containers can look like cardboard. These objects mess up people’s sorting without them even noticing! Even though people said they were confident about what to put in the compost, our look through the garbage suggests people weren’t sure how to sort materials that weren’t always clear to the eye.

Not all of the items that are supposed to be composted at UVic look compostable.

Another misperception about material, when it comes to recycling, is that paper breaks down easily in landfills. And inside our residence garbage bins the most incorrectly sorted material was paper, not plastic (which people often fear more). But when paper enters landfills, it actually takes a long time to degrade! When it does, it has lots of toxins in its ink and bleach that also seep into the environment; plastics, at least, are more stable, William Rathje says.

So, just like we perceive some materials as non-compostable when they are compostable, sometimes we misperceive how materials will act after they are discarded. Will they stay stable or will they leak into the groundwater? Are they ‘biodegradable’ or do they just break down into microplastics that contaminate the ocean? There’s a lot we can’t tell just by looking.

Garbology reveals how we don’t always perceive what will happen to an item after disposal

So how can we get better at sorting on campus?

We want to use Anthropology to improve how people sort trash on campus. This means listening to people we surveyed and making bins like compost much more available and accessible (See why accessibility is vital to driving recycling behaviour here).

It means clearer instructions on bins and items, not on UVic’s online policy (which no one checked!). It means basing solutions on real human behaviour. If we printed ‘Empty this coffee cup!’ on campus cups and attached sinks to compost bins, would more people pour out their coffee correctly instead of contaminating the recyclables? Could colour-coded stickers on UVic packaging direct where more confusing items go and combat mistakes people made when sorting?

The inaccessibility of sorting stations on campus and the high percentage of incorrectly sorted trash on campus may be problems best solved by looking at real-life human behaviours–the goal of Anthropology. Identifying practical solutions for problems faced by people on campus when sorting trash can test solutions to be implemented in community policies for reducing waste on a larger scale.

Through Anthropology, “the accumulation of refuse can be viewed not as a crisis, but a manageable task.” – William Rathje

https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1993-07-17-mn-14066-story.html

0 Comments