Chinese Canadian young adults’

experiences of parental monitoring

Vivien W. Y. So, MSc, & Catherine L. Costigan, PhD

Introduction

It is critical to support the optimal development of Chinese Canadians and Americans as they are large, growing, and integral parts of North American society. Research suggests that many Chinese parents remain highly involved in the lives of young adult children. Little is known about how and why parents monitor their young adult children. Monitoring may extend for a longer time period among Chinese origin families compared to Western norms due to the centrality of family in Chinese culture and norms of lifelong parental authority and involvement. Further, monitoring may take different forms

and tones in young adulthood due to shifts in family living situations (e.g., child moving out) and parent-child relationships (e.g., more equality). The purpose of this research is to understand how Chinese Canadian young adults are monitored by their parents and youths’ perceptions of parents’ motivations for monitoring.

Methods

Sample: Chinese Canadian young adults (N=67) aged 18-30 years, born in Canada or if born outside of Canada, immigrated to Canada before age 15, raised by at least one Chinese parent who immigrated to Canada as an adult.

Gender |

76.40% Female |

Age (years) |

M = 24.45, SD = 4.02 |

Generational Status |

60% Canadian born |

Age at Immigration (2nd generation; years) |

M = 7.91, SD = 3.97 |

Occupation |

58.20% Employed Full-Time44.20% Full-Time Student |

Living Situation |

54.50% Living with parent(s)25.50% Alone or roommates20.00% With spouse/partner |

Province of Residence |

52.70% British Columbia41.80% Ontario5.50% Alberta |

Procedure & Measures: Participants completed a 10-minute online survey and were asked to:

1) Freely list all the ways in which their parents currently found out information about them,

2) Freely list all the reasons they believed their parents were motivated to find out information about them,

3) Answer questions about their demographic information, living situation, and frequency of contact with parents.

Freelists were cleaned and coded by a team of 3 (2 RAs and first author).

Results

Parental Monitoring Behaviours

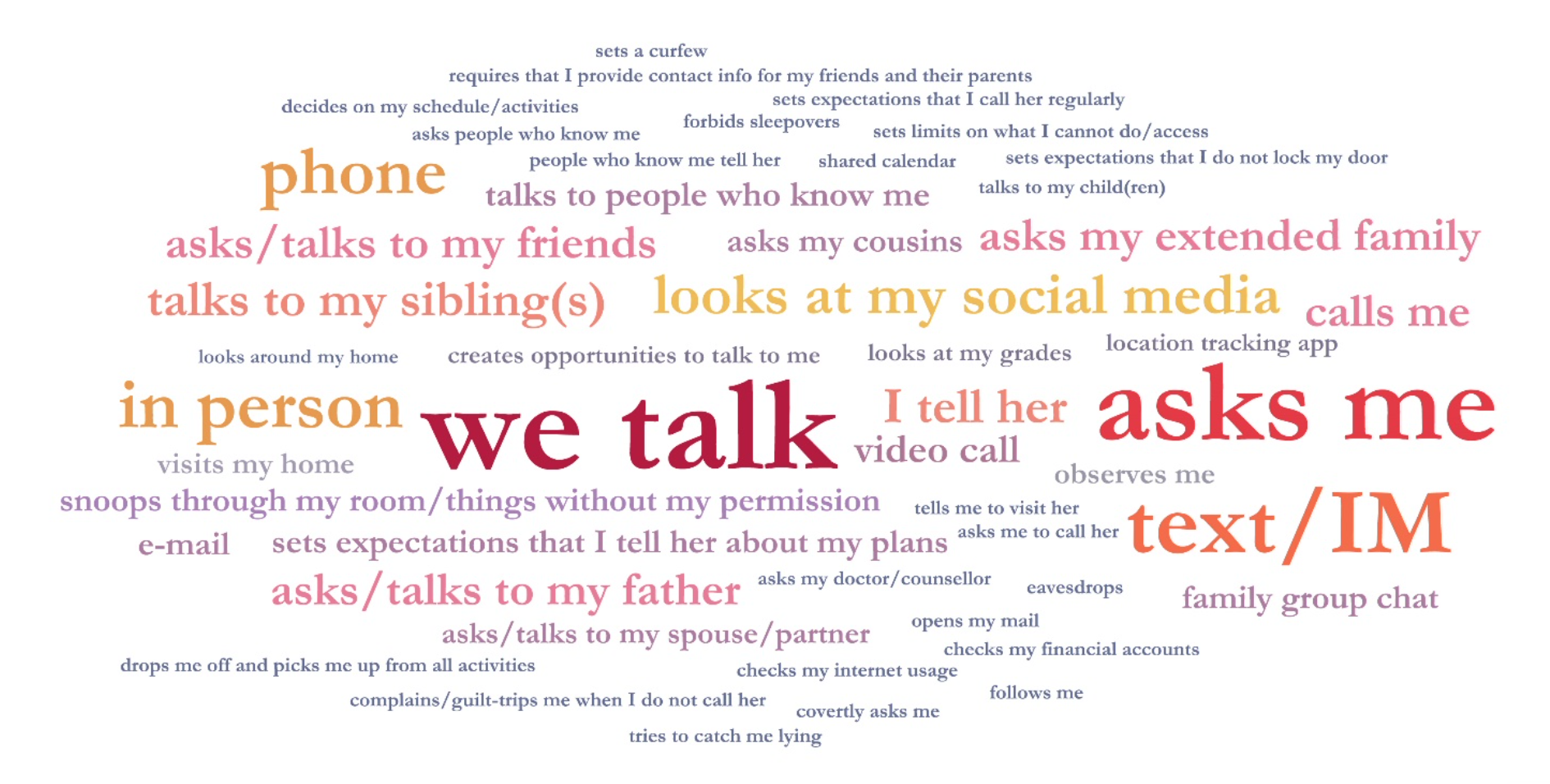

Mothers’ behaviours

On average, 4 distinct behaviours were listed by each participant (range from 1 to 12).The most frequently reported monitoring behaviours were mother-child communication, with mother-initiated communication, parent-child mutual communication and child-initiated disclosure. Other frequently reported behaviours include mothers asking child’s siblings, looking at children’s social media.

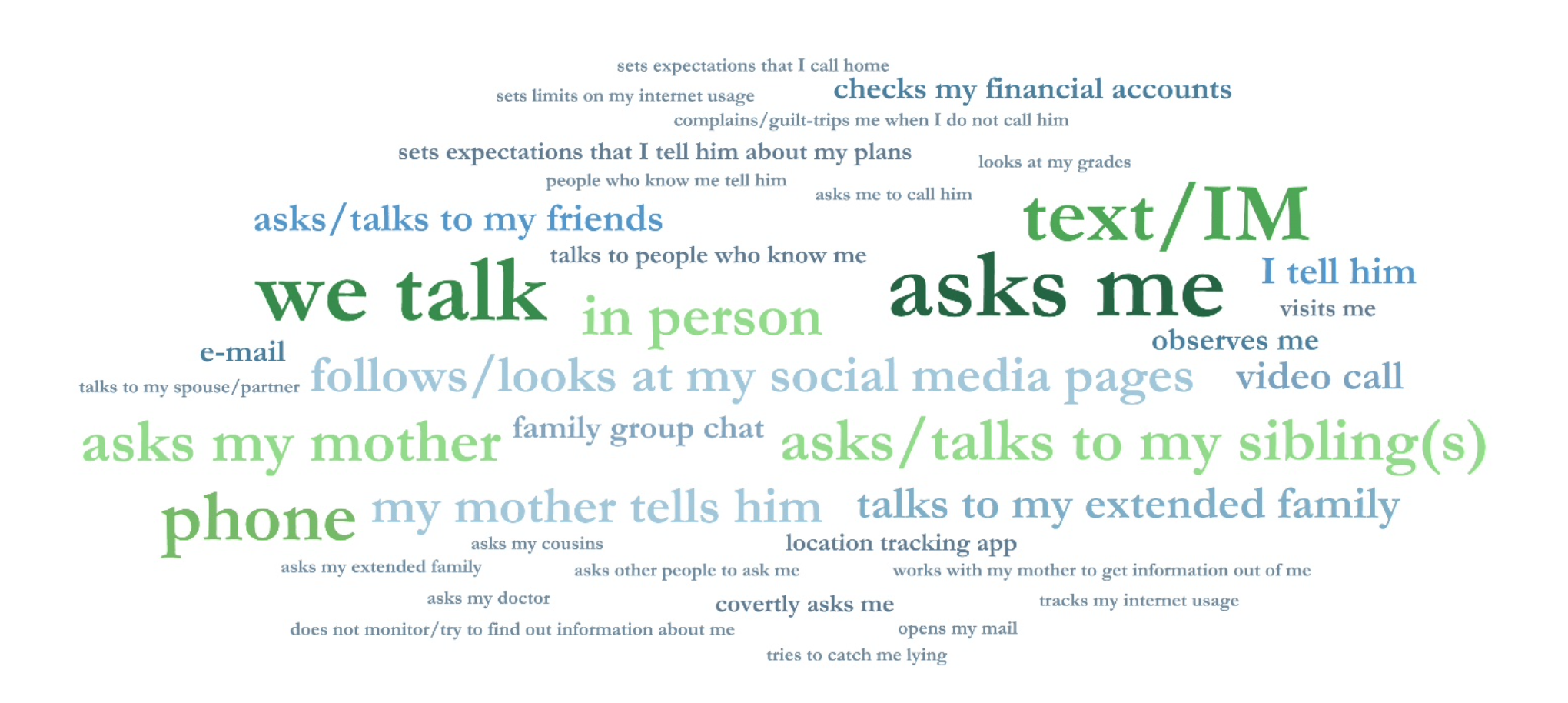

Fathers’ behaviours

On average, 4 distinct behaviours were listed by each participant (range from 1 to 15). The most frequently reported monitoring behaviours were father-initiated communication with children and father-initiated communication with mothers, father-child mutual communication and mother-initiated communication with fathers.

Parental Motivations for Monitoring

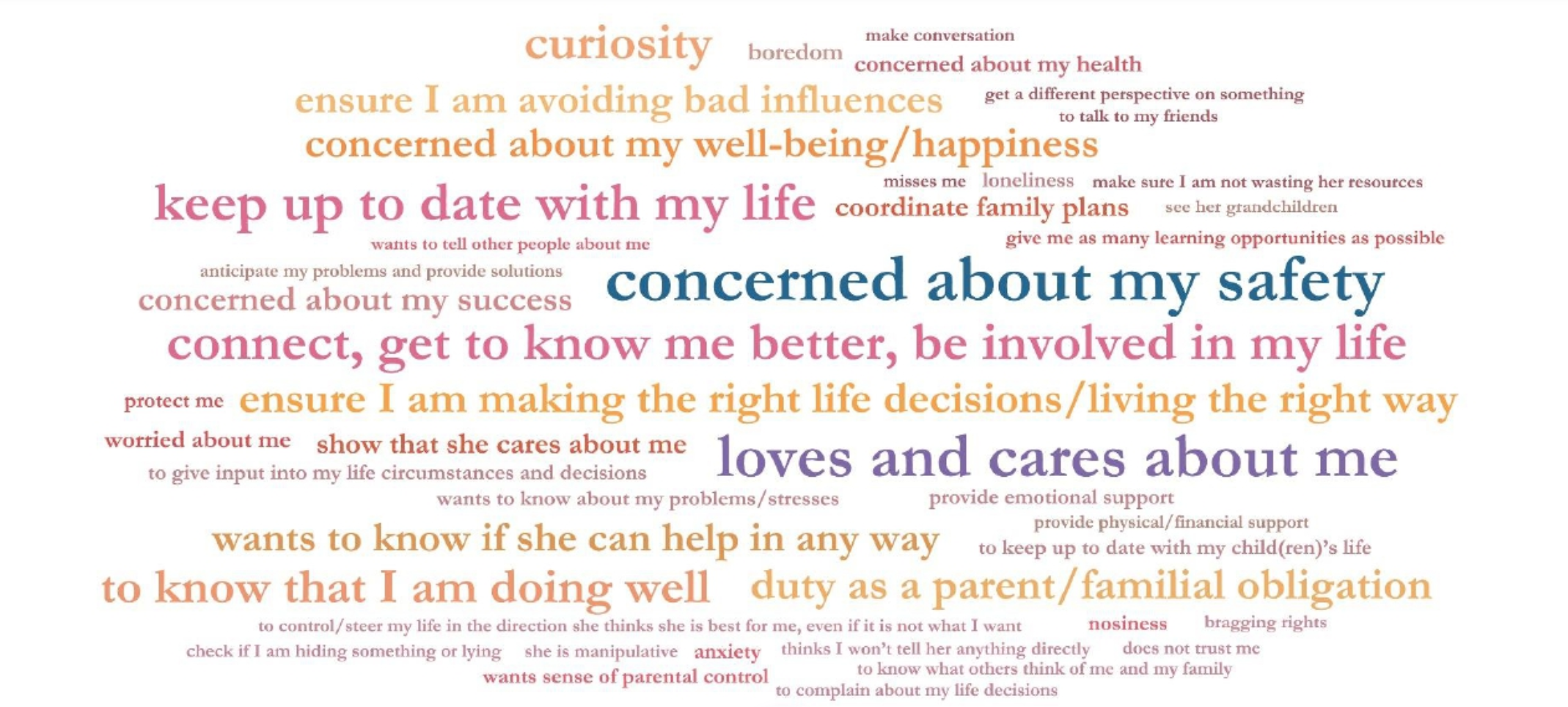

Mothers’ motivations

On average, participants reported 4 motivations (range from 1 to 13 motivations), with a total of 47 distinct motivations were reported. The most frequently reported motivations were concern for child’s safety, love and care for child, wishes to connect with child. Three participants reported their mothers as having no strong motivation.

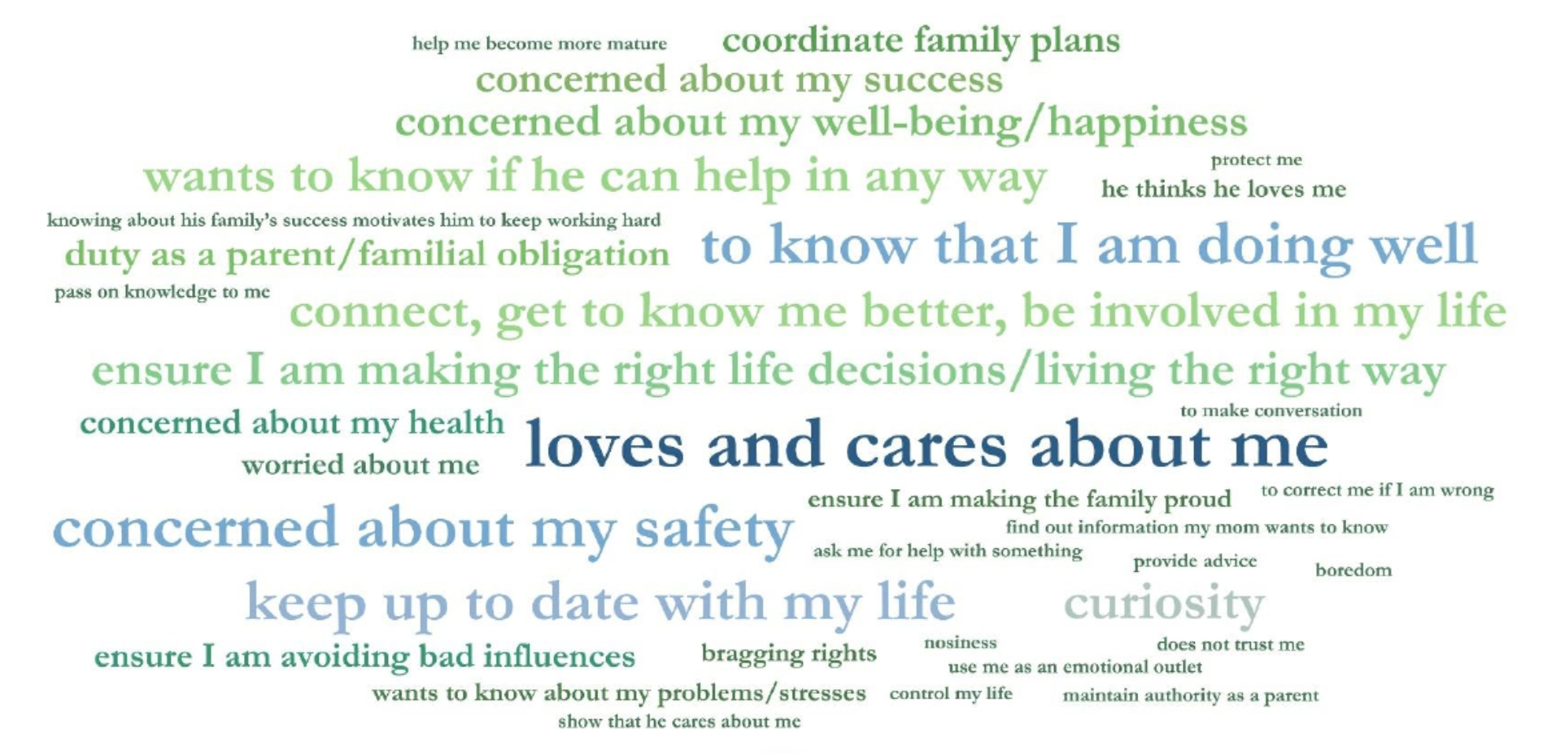

Fathers’ monitoring

On average, participants reported 3 motivations (range from 1 to 7 motivations), with a total of 39 distinct motivations were reported). The most frequently reported motivations were love and care for child, concern for child’s safety, and wishes to know child is doing well. Four participants reported their fathers as having no strong motivation for monitoring. A small minority of participants reported fathers not monitoring them so he can give them freedom, and because it was not his role to do so.

Discussion

Monitoring in young adulthood versus adolescence

- Notable overlap with monitoring in adolescence (e.g., parental solicitation, child disclosure).

- Some behaviours were more relevant to young adulthood (e.g., monitoring social media).

- Control-based behaviours, which are more developmentally appropriate in adolescence, were rarely reported (e.g., setting limits on activities, curfew).

- Some behaviours were consistent with overparenting and helicopter parenting (e.g., snooping, guilt-tripping), both more commonly studied in young adulthood.

Mothers’ vs fathers’ monitoring behaviours

- Participants listed notably more distinct monitoring behaviours for mothers (66) than fathers (54). Mothers may be more involved and in more different ways in young adults’ lives than fathers are. This is further supported by the higher frequency of reports that fathers learn about their young adults through mothers, compared to the reverse direction.

Parental motivations for monitoring of young adult children

- Most frequently reported motivations for both mothers and fathers were benign (e.g., love and care for child, connection with child, concerns for child’s well-being)

- Culturally relevant motivations included parental duty/familial obligation, wishes to know if child is maintaining a good image for the family, and to ensure children are provided for

- Several participants reported parents as having little motivation for monitoring, particularly for fathers; some indicated fathers purposefully not monitoring because it was not their role

- Several participants reported intrusive motivations suggestive of maladaptive family dynamics (e.g., parent does not trust me), and overparenting (e.g., steer child’s life toward parent-desired direction)

Future Directions

- Examine frequencies of parental monitoring, desired levels of parental monitoring, and their links to young adult well-being in larger sample

- Examine whether objective frequencies of monitoring behaviours or match between desired and actual levels of monitoring are more predictive of young adult well-being and parent-child relationship quality

- Examine whether benign motivations for monitoring buffer effects of parenting discrepancies on youth well-being