“That sounds kinda sad,” My coworker’s mouth twisted.

I had just told her that I was going to be participating in a cemetery field school. I get her reaction- death is a lot.

But sadness wasn’t at the forefront of my mind that Thursday.

We started off the morning breaking off into pairs to record graves. Documenting graves is important- no stone lasts forever. But good records keep the info they contain safe for future generations.

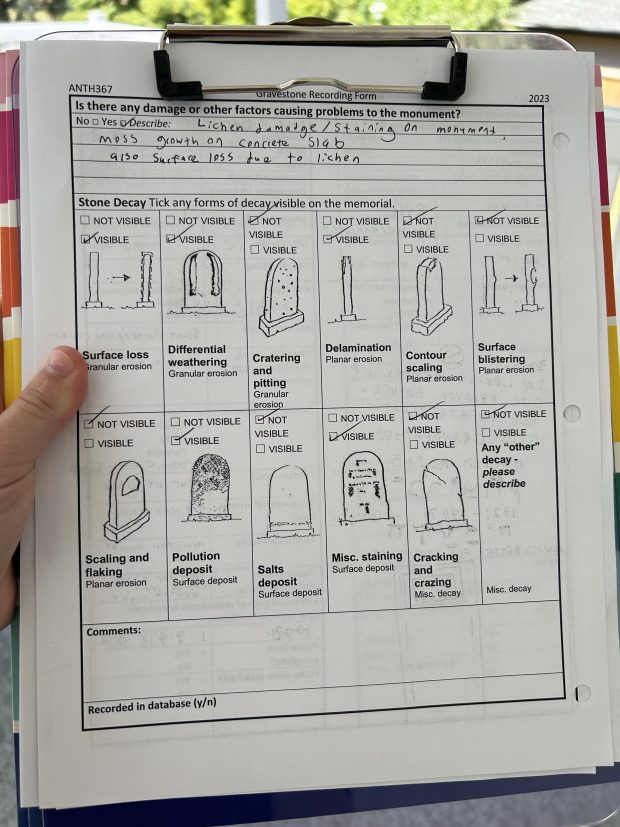

Armed with our trusty field manuals, we noted the inscription, gravestone material, dates etc. All pretty straightforward.

Assessing the damage to the stone? Not so simple. It turns out a lot of things can damage a tombstone– weather, pollution, moss and more. It’s important to document though so we can make decisions around conservation.

To me, studying graves is a kind of sacred practice. I say the deceased’s name aloud. I think of the life they may have lived. And, I think of the people who created this “Cultural landscape.”

A Visit to the Rabbi

After recording, we zipped down to Congregation Emanu-El to meet with Rabbi Harry Brechner. We were fortunate to visit him at the oldest surviving synagogue in Canada. It’s a beautiful red brick building, with a peaceful inner sanctuary illuminated by stain glass windows.

Jewish settlers came to Victoria from California for the Gold Rush in 1858, and quickly created the cemetery in 1860, and synagogue in 1863. Both spaces are still in use today.

In the sanctuary, Rabbi Harry taught us what death and burial means in the Jewish tradition.

Full disclosure: I’m not religious, but was raised with a Protestant-ish worldview. So that’s my cultural baseline for death.

There are important differences between the two:

First, the Jewish Community was into green burial before it was cool. When a Jewish person dies, they are meant to return fully to the earth. That means nothing gets buried that won’t easily decompose. And, of course, no embalming.

The deceased should also be buried ASAP- ideally within 24 hours of death. This is so their soul can move on, and loved ones can start to properly mourn.

Community members sew the simple linen clothing that the dead are buried in. They also clean the body. Coffins are likewise simple and made of pine- even the handles are made of biodegradable hemp.

The Rabbi emphasized this is the standard, no matter how rich or poor the person was- there is equality in death. And, the community cares for the dead and for the family every step of the way.

This care moved me.

The deaths I’ve experienced have been medicalized– lots of hospitals, not much community. Not a lot of space for actual grief. I can appreciate the difference a good ritual would make.

Rabbi Harry also shared the ‘why,’ behind some of our protocols at the Jewish cemetery. For example, we don’t do any fun activity in the cemetery that the dead can’t do- like eating. That’s why we lunch outside the cemetery gates.

He also spoke about memory.

On our first field-day, we encountered the grave of a young child who died in 1871. On her grave was a stone- someone had visited her- probably a distant relative, the Rabbi said.

Someone remembered her.

Like Rabbi Harry explained, a headstone is an “Anchor for memory.” Even 150 years later.

Meeting the Residents of the Cemetery

After meeting with Rabbi Harry, we went back to the cemetery for a chat with former Cemetery Director Dr. Rick Kool, and tour with Cemetery Historian Amber Woods.

They acquainted us with some of the people buried here, including the brave souls who had survived the holocaust. Amber also gave us some history of the early Jewish Community in Victoria. Her stories and photographs cemented why we are here.

It brought home that our work is about real humans- both living and dead. It’s a privilege.

And, don’t get me wrong, I actually love some good anthropological theory (Thanks, Dr. Campeau Bouthillier).

But, there is something special about getting to do Anthropology In Real Life.

That’s why I feel more grateful than sad. We get to be here, in this sacred space. And, hopefully, we too can add something (even something tiny) to this long legacy of care.

How do you relate to cemeteries in your life?